Reading the texts that adorn the walls of Don McCullin’s retrospective at Tate Britain in London, one can sense the institutional nervousness. This is a show, after all, in which a white, male, Western war photographer turns his lens on the destitute, the embattled, the starving, the injured, the dying and the dead. Many of these subjects, whether they suffered the famine of Biafra in the late 1960s or were slain in the Vietnam War, are people of colour. All are vulnerable. The museum is at pains to stress McCullin’s ‘empathy’, that these signature high-contrast black-and-white images, captured over forty years of newspaper assignments to warzones across the world, were taken ‘with great respect’ and aimed ‘to create a voice for the people in those pictures’. And yet the fear of reviving recent controversies around the representation of others’ suffering by artists including Dana Schutz and Luke Willis Thompson echo through these statements.

Ethical debates around the representation of atrocity in photography have a long history. In her 1981 essay ‘In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on documentary photography)’ the artist Martha Rosler noted that the medium carries ‘information about a group of powerless people to another group addressed as socially powerful… the liberal documentary assuages any stirrings of conscience in its viewers the way scratching relieves an itch and simultaneously reassures them about their relative wealth and social position.’ The presentation of photography from conflict zones in a gallery will always work across an uncomfortable power differential: the stricken have given their image (whether with explicit consent or otherwise) for the better understanding and perhaps even the ultimate improvement of their circumstances (notwithstanding ‘the disappointed belief in a straight line … between perception, affection, comprehension and action’ that Jacques Rancière identifies at the root of our contemporary scepticism about images with a social agenda).

In one starkly titled photograph, Starving 24 year old mother with child, Biafra (1968), a baby pulls uselessly at a woman’s empty breast. The heads of both mother and child are grossly oversized to their emaciated bodies, and even to describe such a scene from the comfort of an office, warm and fed, feels barbaric. A few days later I visited the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize. Hung in a room at The Photographers’ Gallery is the shortlisted work of Susan Meiselas, which includes harrowing images of the mass graves of Kurdish Iranians executed in the First Gulf War. Publication of such photographs in the news media serves a basic journalistic function, but what does showing them in a gallery achieve?

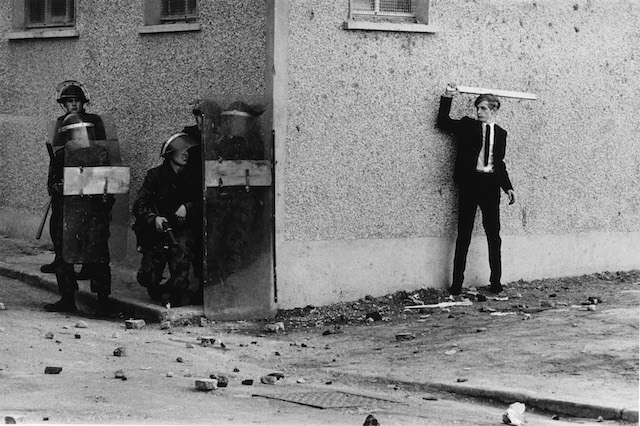

McCullin’s work – and the hang of the Tate show – goes a long way towards confronting questions of ‘privilege’ by asserting a basic humanism, without the need for the supplementary special pleading. The exhibition opens with his earliest photographs, of the postwar streets of the artist’s North London neighbourhood (I peer into them, wondering if I might catch a glimpse of my dad, a kid in the 1950s growing up in Finsbury Park’s Italian immigrant community). Those depicted may not be starving, but there is poverty and this isn’t, for much of Tate Britain’s audience, some exotic ‘other’ but a Britain within living memory and indeed, after the UK government’s recent policies of austerity, not far removed from the streets of today. McCullin’s images of Checkpoint Charlie and the Berlin Wall, taken in 1961 on his first professional assignment, remind us that this kind of curiosity about our fellow beings is instinctive: a photo of West Berliners peering over the wall at their brethren is hung next to a shot of a similarly inquisitive crowd on the GDR side. Motifs of looking abound: a man peers across the border through binoculars; when a little girl is pictured surrounded by soldiers, a gent in the background brandishes a camera. Collectively they convey a sense that to look is to familiarise oneself with an ‘other’, that to familiarise is to empathise.

McCullin’s photographs at the Tate were almost entirely the result of newspaper assignments, most notably for TheSunday Times, and yet are presented shorn of the written reportage that originally accompanied the images. In many ways this is a return to the first mode of distribution for conflict photography. Over at the Queen’s Gallery, an institution neighbouring Buckingham Palace and showing works from the Royal Collection, a small exhibition tells the story behind one of the earliest war photographers, Roger Fenton, and his images from the conflict in Crimea (1853–56).

The war with the Russian Empire had caught the imagination of the public, despite condemnation in the press of Britain’s involvement, and Prince Albert, a patron of Fenton, encouraged the photographer to travel to the battlefield. He arrived on the scene in 1855, too late for most of the action and burdened by his equipment: one photograph shows the horse-drawn cart that doubled as the lab in which Fenton prepared the glass plates before going out in the field and where he later processed them. His images are tame in comparison to McCullin’s – the long exposure meant Fenton’s subject matter had to be perfectly still (or dead, as in Mathew Brady’s corpse-littered images of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863) – and it wasn’t until the Boer War (1899–1902) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) that the white heat of battle was captured on film. Yet there was enough danger for Fenton to have taken the picture of the wagon, which he feared would be destroyed by an offensive the next day. Writing to his wife from the siege of Sevastopol, Fenton described a near miss. ‘I did not see as a shell came over about the same spot, knocked it [sic] fuse out & joined the mass of its brethren without bursting. It was plain that the line of fire was upon the very spot I had chosen.’

The morbid romanticism of the Victorian public was evidenced by the popularity of Lord Alfred Tennyson’s perversely triumphant Crimean paean, ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ (1854) and the publisher Thomas Agnew & Sons, Fenton’s sponsors on the trip, had hoped to capitalise on it through print sales of the photographs direct to the public (some of the images did end up published in the Illustrated Evening News). One depicts a wounded soldier: the man lies with his head resting on the lap of a comrade, his gun lying on the ground parallel to his exhausted body. A vivandière, a nurse who would have travelled with the regiment, administers a glass of dark medicine, or perhaps just a stiff drink. The image is beautifully composed, and Fenton wrote that the subjects ‘enjoyed’ having their photograph taken, so it is unclear whether what we are witnessing is natural or staged. While today we value a particular idea of authenticity – in a wall text McCullin notes that he only once staged an image, placing the treasured possessions of a dead Viet Cong solider, which had been scattered during looting, next to the man’s body – for Fenton, the end result was more important.

The most affecting pictures in this small exhibition are those of the landscape after battle. An image dated 23 April 1855 shows a vista in which rocky, dusty inclines meet at the faintest semblance of a path. Fenton borrowed his title for the work, The Valley of the Shadow of the Death, from Psalm 23. Humanity is physically absent, but every canonball on this miserable bit of land seems to call up the ghosts of the slain. This photograph, and two more murky landscapes which show in the foggy, distant Sevastopol, a city in present-day Russian-occupied Ukraine, reminded me of the final room of the McCullin retrospective. The latter’s most recent photographs capture similarly foggy meadows in England’s West Country where the photographer, now in his eighties, lives. Likewise, while bucolic, it feels as if the spectres of McCullin’s memory haunt that landscape.

An American photojournalist best known for her reporting from the drug wars of Nicaragua, Susan Meiselas’s presentation in London derives from an invitation by Human Rights Watch to document the organisation’s work uncovering unmarked mass graves in Iraq. Three photographs grouped together set the solemn tone: a woman lifts up the back of her jumper to reveal the scars of torture; a group of Kurdish villagers crowd to watch an exhumation; a forensic anthropologist stands in a hole in Erbil, clutching the blindfolded skull of an executed teenager. And though it also acts as a monument to the victims of war, Meiselas’s work might offer a more complex vision of the role of conflict photography than McCullin’s more straightforward documentary. In a slide projection populated with further images – her own and found – Meiselas questions her role through a series of intertitles: ‘I began to wonder about all the photographs that had been made and taken from Kurdistan,’ reads one; ‘I can’t escape the tradition of the colonial foreigner,’ acknowledges another. This is a body of work versed in the problematic ethics of the medium. Yet Meiselas also celebrates the power of images. Given the persecution of the Kurdish people in Iraq, she notes, ‘Even a family portrait is an expression of identity and could be deemed subversive.’

These queries prompted her to record the testimony of witnesses and collaborate with the subjects of her images, and so she searched out vernacular photos representing Saddam Hussein’s campaigns against Iraq’s Kurdish population and the violent struggle for Kurdish recognition more generally, from personal collections in Iraq, Turkey and Iran as well as those stored in Western archives. On a visit to Tehran, Meiselas came across a photography studio run by a Kurdish man. In the intertitles she explains that, intrigued, she asked if she could leaf through his archives: his most treasured image dated from 1900 and showed a group of men hoisting up spikes on each of which is impaled the head of a Kurd. The man kept the picture to remind himself of the suffering that had beset his people. Like the Tehrani studio manager, we need to face horrific images. Not because it will necessarily galvanise change (it might, on a local level though) but to understand what people are capable of.

There is no doubt that we are suffering from atrocity fatigue. As far back as 1964 Dorothea Lange, a giant of twentieth-century documentary photography, complained that ‘it takes a lot to get full attention to a picture these days, because we are bombarded by pictures every waking hour, in one wielding a bullwhip form or another, and transitory images seen, unconsciously, in passing, from the corner of our eyes, flashing at us, and this business where we look at bad images – impure. I don’t know why the eye doesn’t get calloused as your knees get calloused or your fingers get calloused.’ In the digital age, such images of suffering are more readily available than ever.

Susan Sontag argues, in ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’, that to hang an image in a gallery automatically renders it art ‘whatever the disclaimers’. I am minded to agree. While she also argues that this aestheticisation of trauma is problematic and that the space of the museum is ultimately one of leisure, it nonetheless remains true that such institutions provide an enclave from the rest of the world in which the act of looking is primary. We cannot ignore the picture on the wall; we cannot pretend we did not see. There are no newspaper adverts, no server tabs to rescue us. Perhaps we need these images to be presented as such – to be aestheticised, in the sense of quarantined from the distractions of the world – if they are to gain our full attention. The horrors of the three shows I saw within a week of each other spanned 150 years: this suffering is not an aberration particular to our age. This is us. And if galleries are not places in which we can confront and attempt to better understand the human condition, then it is hard to know what they are for.

Don McCullin’s retrospective is on view at Tate Britain, London, through 6 May; Susan Meiselas’s work is included in the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2019 on through 2 June at The Photographers’ Gallery, London; Roger Fenton’s photographs can be viewed at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, through 26 April

From the April 2019 issue of ArtReview