by Georgina Adam

Lund Humphries, £19.99 (softcover)

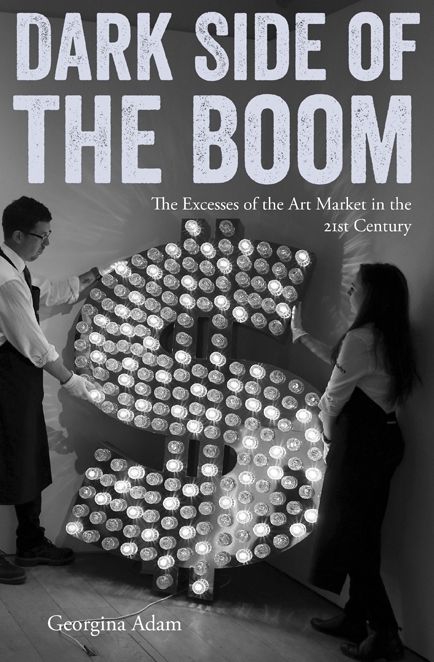

A veteran art-market journalist, Georgina Adam is discrete and observant, and good at navigating the elite social-scene and culture of the art market beyond the noise of auction prices. If her 2014 book Big Bucks: the Explosion of the Art Market in the 21st Century charted the wild ride of commercial expansion at the turn-of-the-millennium (asking whether the art-market boom would ever stop), her new work revisits many of the earlier book’s themes in the light of the art market’s relative slump from 2015. It’s a gloomier take, in which Adam focuses on the ‘excesses the explosion in the market in the twenty-first century has brought in its wake,’ among which she includes ‘the active branding of art and artists as a commodity, the buying of art for investment or speculation, the temptations of forgery and fraud, conflicts of interest, tax evasion, money laundering [and the] pressure to produce more and more art.’

as Adam points out, ‘art’s special qualities of portability means it can be bought with one currency in one country, but resold in another – acting in effect as a sort of alternative currency or shadow money.’

The book is an engaging introduction to these less visible background dynamics, compiled from Adam’s reporting of legal cases, auction results, big gallery and institutional developments and interviews with various industry players, some of them braggingly public, others o -the-record, no-names-please shy. That Adam chooses to focus on such things as the growth in freeport art-storage, the obsession with art as an investment opportunity, speculative buying and the litigious quagmires of copyright and authentication is meant to highlight how much money has become an end in itself within the shadowy corridors that connect galleries, auction houses and art advisors eventually to the global class of the ultra-rich.

Adam’s accounts of the excesses is certainly entertaining; of visiting Zhang Huan in his vast studio-factory in Shanghai, the artist piqued when Adam tells him she’s going to Sterling Ruby’s studio in Los Angeles, which, she believes, is ‘just as big’; of the relentless legal skirmishes of appropriation artists like Richard Prince or Jeff Koons, endlessly in and out of court battling with pissed-o artists claiming they’ve plagiarised their work; of the gala dinner that opened Shanghai’s West Bund art fair, where 360 uber gallerists and collectors are served ‘sea cucumber intestines nestling inside frozen globes’ by 40 radio-earphone-choreographed servers. Indeed, the rise of China features in its own chapter, signalling the increasing importance of the Chinese market and of its dynamic and fabulously wealthy collectors, and China’s staggering rush to build museums, largely driven by tax incentives for big property developments, but where political and economic volatility has encouraged many wealthy Chinese to get money out of the country (especially after the 2015 devaluation of the Yuan), often through buying art in the West.

Lying behind much of Adam’s disquiet is this obscure dynamic of liquidity seeking out art. As she writes of the expansion of freeport art-storage, ‘this plugged into a shift in how the uber-rich were investing their money, by increasingly accumulating tangible assets such as wine, art and vintage cars, particularly after the global financial crisis of 2008-9, when interest rates on other investments plunged to rock bottom.’ And as she points out, ‘art’s special qualities of portability means it can be bought with one currency in one country, but resold in another – acting in effect as a sort of alternative currency or shadow money.’

The real limitation of Dark Side of the Boom is that, while it looks at the art market’s continued relative robustness, even after 2015, there’s no closer explanation of why there’s still so much cash in a period supposedly marked by slump, particularly in the West, and slowing growth elsewhere. Yes, ‘there is the chance of making extraordinary pro ts on art, at a time when other investments have offered poor or non-existent returns,’ Adam writes, and the excesses she describes are no doubt driven further by this new context. But how the global space of the commercial art market intersects with the wider machinery of the global economy remains only glimpsed. What lies beyond is the real dark side of the art boom. J. J. Charlesworth

From the December 2017 issue of ArtReview