While many of the products of Japanese manufacture and design are known internationally, and the nation has long been exporting its pop culture in the form of music, animation/manga, films, video games and various sub-cultures to Asia and the world, broadly speaking its contemporary art remains a domestic phenomenon. It is certainly the case that relatively few young Japanese artists, often collaborating with luxury brands and fashion houses, have entered public view internationally.

The biennial Nissan Art Award is one of the vehicles set up to combat this and the five finalists for this year’s edition each present a new work at BankART1929 in Yokohama. Beyond the competitive agenda, the award exhibition provides an opportunity to examine the output of a generation of artists in Japan who are emerging from an age that has been defined by the politics of Shinzō Abe and the lasting impact of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

The exhibition begins with the work of Ryuichi Ishikawa, a photographer who believes that his medium allows for a ‘confrontation’ between the artist and the world. His project here is a collection of photographs of daily life in his hometown, featuring depictions of his bedroom, living room and toilet, and more intimate details such as the toys his child leaves lying around the home. It also includes ostensibly less personal photographs of US military planes flying above Okinawa – sometimes so close to the buildings that they look as if they might be plucked from the window – but this is in fact an occurrence that is so regular in the city that it forms just another aspect of domestic life. Riffing off a tradition in Japanese photography of recording daily objects, the series is an ode to everyday life, honest and intimate, that ultimately reveals the sensible truth of the country to be a far from normal state of being.

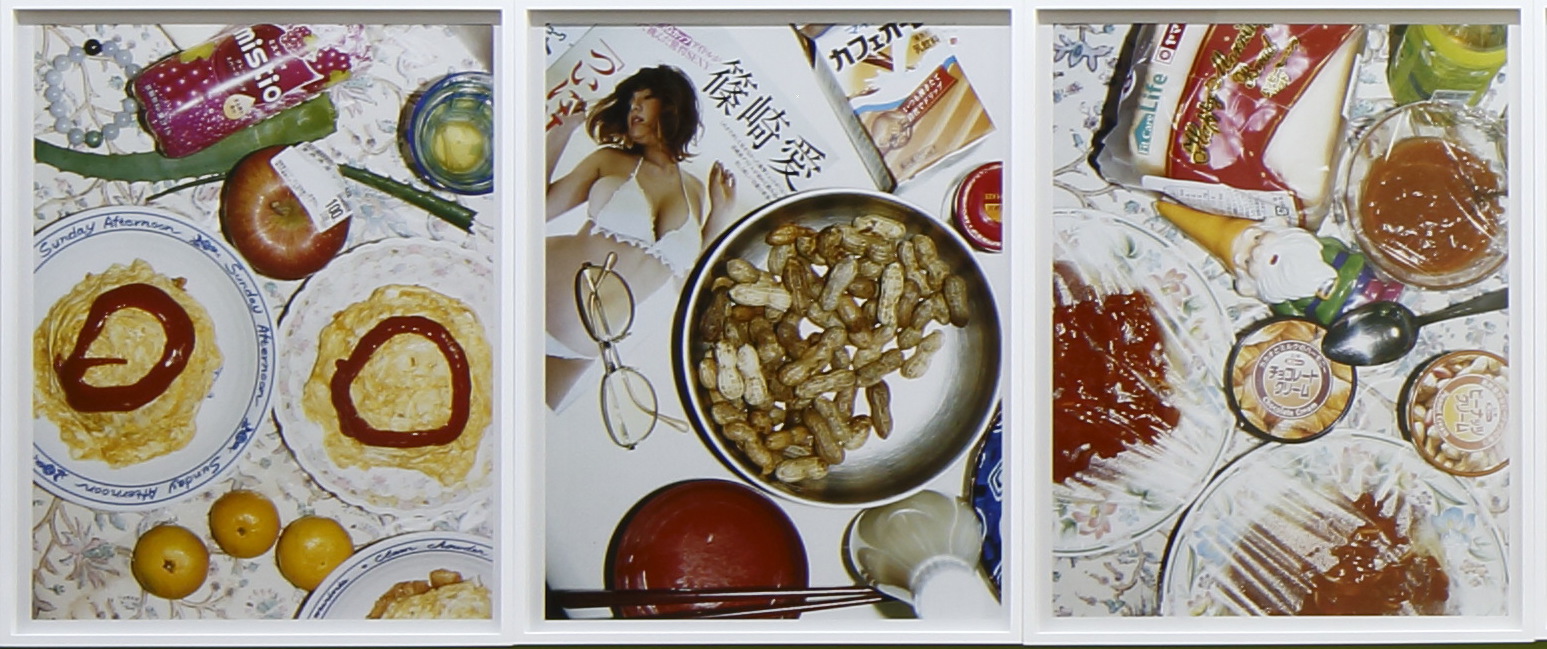

The photographs of another finalist, Motoyuki Daifu, also focus on quotidian life – in this case his daily meals, often comprising microwave foodstuffs, and canned and packaged products. On the one hand this is a celebration of sometimes garishly colourful (or colourfully packaged) food; on the other hand it documents commodities, consumerism and excess. More minimalist is the work of Nami Yokoyama, the only female artist and the only painter included in the exhibition. She presents a set of paintings of neon texts and graphic patterns (a Christian cross, cartoon-style characters and texts about art history and painting). While the work signals a conceptual turn in her painterly practice, it is also another rendition of Japan’s dominant consumer society.

Yuichiro Tamura’s installation End Game (2017) features three theatrical stage settings: a ‘sculpture workshop’, in which a Corinthian pillar is being processed from the engine of a deconstructed Gloria (a signature Nissan car series, first launched during the 1960s), a typical Japanese interior decorated with objects imported from the West including a pianola that plays Gloria from Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis (1819–23), and lastly a small glass-walled room papered with news stories about Laura Branigan, singer of the 1982 cover version of Umberto Tozzi’s 1979 disco hit Gloria, inside of which a three-channel video showing the deconstruction of a silver Gloria and the reuse of its materials into the pillar and two trash bins (these last echoing the symbolic props from Samuel Beckett’s 1957 play Endgame) exhibited in the installation. By dispatching various cultural and historical references, Tamura illustrates how the idea of glory, as one driving force in cultural production, is born, grows, exists, ends and is then transformed.

In a sense, you start to get the feeling that the artists on show here play a role in modern society that is rather like that played by Godzilla during the 1950s: they are a product of their time, and simultaneously the destroyers of it and (potentially) the creators of a new future.

Hikaru Fujii, born in Tokyo and the winner (selected by an international jury) of this year’s grand prix, uses documentary, video art, archival material and workshops to reflect on what it means to be Japanese. Playing Japanese (2017), inspired by British clergyman H.N. Hutchinson’s 1901 ethnological study The living races of mankind and by the Osaka Expo of 1903 (which featured many anthropological displays, among them a ‘Human Pavilion’), is a multi-video documentary installation of a workshop in which participants were invited to ‘play’ the Japanese of 1903, observing the indigenous peoples of Hokkaido, Okinawa, Taiwan and Korea through a Western perspective. By bringing a historical context back to life, participants and viewers are able to stand in the broad scope of history to examine the difference and commonality between people of today and of a century ago, to witness the violence of colonialism, and how anthropology was once used to help Japan build up its national identity and imperialist vision. Aside from the historical studies and performative workshop, Fujii uses a video language that is quiet, calm and poetic, and distinct from many other documentaries.

As the winner of the Nissan Art Award grand prix, Fujii will be supported in taking up a residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in New York. One tiny step towards building an art scene free from Japan’s inherent isolation.

From the December 2017 issue of ArtReview