In the Emmiyengal language, ‘karrabing’ describes the time at which the tide is furthest from the shore. It also alludes to the coastline that connects the homelands of the extended family of the Karrabing Film Collective, defining neither a specific place nor a fixed identity but a fluid body of people. Membership of the group, all but one of whom are indigenous Australian and were born in the rural Belyuen community that has grown from a 1940s internment camp, continues to swell. “We’ve always said 30,” founding member Elizabeth Povinelli says, “but now we’re saying 50, although really there might be 70.”

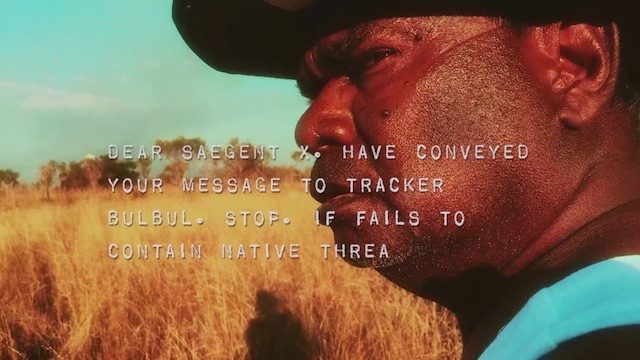

The collective has over the past decade produced a body of work dramatising the conditions – social, political, temporal – in which its members live. The central subject is the struggle to adapt to the more insidious everyday interventions of the state (the intrusion into their small community of police officers, housing corporations, social services), resist the pressures of extractivism and capitalism and maintain their connections to each other and their ancestral lands. Scripted, acted and directed by members of the group, its films challenge the narratives imposed on marginalised communities by those in power. A palpable anger is leavened by empathy, wit and humour: those new to its work might start with the satirical Night Time Go (2017), which combines doctored archival footage with a quasi-British Pathé voiceover to tell an alternative history of the Belyuen community.

It is not only straightforwardly racist narratives that Karrabing exists to rebut but also the liberal forms of indigenous recognition that emerged during the 1970s. Often starting from fictionalised versions of mundane happenings – the threat of eviction, the imposition of a fine by the police or the illegal incursion of a mining corporation into protected land – the collective’s films discredit a model of indigenous identity as consisting exclusively in an anachronistic set of traditions to which its members must rigidly adhere. When the Dogs Talked (2014), for example, shows a family hassled by welfare officers being forced to choose between acceding to the demands of the state and observing a ritual in their native country. This constant negotiation between conflicting systems informs works such as Wutharr, Saltwater Dreams (2016), in which a group stranded on an island by a broken boat motor bickers about how disgruntled ancestral spirits, uncomprehending state authorities and Christian missionaries have contributed to their predicament. The work acts out the multiple and intersecting realities that constitute indigenous identity: like the sea, it is subject to different forces, is ever-changing, is always connected.

It was in the aftermath of one particularly violent interference that Karrabing Film Collective was founded. A confected moral panic prompted by a 2007 report alleging endemic child neglect in indigenous communities gave the federal government an excuse to introduce the Northern Territory National Emergency Response. Also known as The Intervention, it claimed special exemption from federal laws against racial discrimination in order to enforce a raft of measures against indigenous people. Povinelli, who has been travelling to Belyuen since completing her studies in philosophy in 1984–5, when she was invited by its senior members to become an anthropologist in order to assist them in a land claim, remembers that Australia’s ABC radio wanted to report the issue. But the community felt that whatever they said to a state broadcaster, however sympathetic, would inevitably misrepresent their position. So they went hunting instead, and it was on the way back, Povinelli recalls, “that Jojo [Linda Yarrowin] said, ‘Why don’t we make our own little thing about what’s really going on?’”

“It was not my idea to make films,” Povinelli says, and her initial reaction was to caution against the kind of ethnographic filmmaking that purports to give indigenous communities a voice by simply providing them with cameras. “We know about that way of doing things,” was the other members’ reaction to her warning, “We want somebody who knows what they’re doing.”

A palpable anger is leavened by empathy, wit and humour

Delivered in the community’s creole and often structured according to shifting time signatures, the films’ vitality is instead consistent with their criticism of the liberal assumption that indigenous identity is rooted in a frozen past. Not better than the forms of discrimination that preceded it but “differently bad”, the effect of Australia’s land rights reforms being predicated on a model of authentic, singular and demonstrable indigenous identity was destructive. “A specific anthropological form became the mandate for indigenous people getting their lands back. This foreign form had the effect of dividing communities on the basis of what settlers believed were traditional versus historical relations to land.” The ensuing fragmentation of those groups, Povinelli points out, had consequences including that it was “easier for capital to get in there”.

Capital in Karrabing’s films is represented by the mining corporations that have coopted large swathes of the Australian landscape. In Windjarrameru (The Stealing C*nt$) (2015), four young men are chased by police into private – and poisoned – land. In their experience and the discussions that surround it, an understanding of country as a complexly interconnected system is counterpointed with the Western principle that it can be parcelled up into independent territories (an idea discredited by, among other things, the global ecological crisis so dramatically symbolised by Australian bushfires). But it’s typical of these films that the construction of any simple binary between Western and non-Western ways of thinking quickly breaks down. Doesn’t the indigenous model of dynamic interaction and creative exchange resemble a progressive model for globalisation? And isn’t it the Western principle of sovereignty, individualism and rational self-interest that now seems stuck in the past? “Everybody knows where their country is,” Povinelli cites Yarrowin as saying, “but your own land is connected by story, by ritual, by marriage, by sweat to other lands, so you have to keep them strong if yours is going to be strong.”

Past and present, too, are inextricably entwined. In Wutharr, ghostly ancestors stalk the landscape even as state officials visit the family; The Mermaids, or Aiden In Wonderland (2018) is set in a dystopian near future that also invokes Australia’s shameful history of separating indigenous children from their families for ‘reeducation’ or medical experiment (the destructive consequences of which continue to be felt today). That the present and past are bound up in ways other than the conventionally linear has implications. If the past is not dead – if it is not even past – then these and other state crimes cannot simply be confined to school textbooks and redressed with an apology, however sincere. They continue to act upon the present in ways that must be acknowledged, addressed and incorporated into policy.

Karrabing combines fact and fiction in order to represent the complexity of these intertwining realities. “It’s a story, but it’s real,” according to Povinelli, “not exactly what happens but what happens.” To assume that because these stories are authored by members of a rural Australian community their meaning can be confined to a specific time and place is to ignore the profound entanglements that they enact: these concepts have applications far beyond the local conditions the films begin by describing. As it is impossible to separate the past from the present, so it is futile to attempt to cleanly separate here from there, to establish conclusive definitions of ‘us’ as distinct from ‘them’. As Povinelli says, “it’s all happening in the present.”

Day in the Life, Karrabing Film Collective’s latest film, will premiere at the International Film festival, Rotterdam, 22 January – 2 February. Lunch Run, a new short film commissioned for Projections’ Artists in the Cinema 2020 programme, will launch at Tyneside Cinema, Newcastle, on 28 February before touring UK independent cinemas

From the January & February 2020 issue of ArtReview