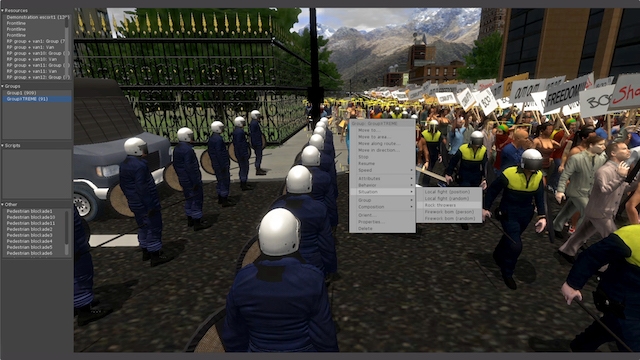

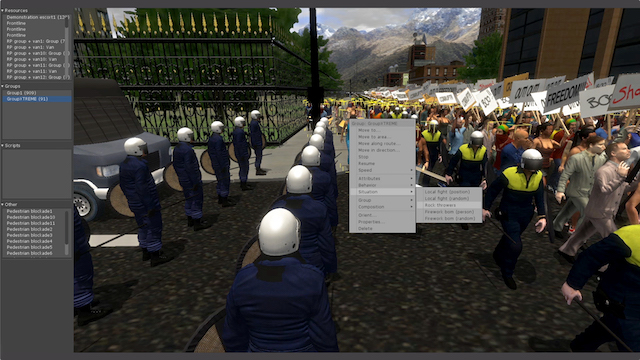

In Stéphanie Lagarde’s 16-minute video Déploiements (2018), the Paris-based artist cuts between footage of a military aerial display team, the planes’ vapour trails often taking the patriotic red, white and blue of the Tricolore, and an animated rendering used to train police in crowd control. The latter is introduced via a simulated aerial view of an empty city, before a computer cursor appears, hovers over an imaginary street and, with a click of the unseen animator’s mouse, adds a line of identical police officers to the scene. A crowd of demonstrators holding generic placards are conjured up in a similar fashion, and begin to advance on the police.

The video runs through various possible behavioural scenarios for the demonstrators – their movements hectic and confused compared to the calm advances of the uniformed police – most of which end in their containment by the authorities. What becomes clear in Lagarde’s work is the tension between the rehearsed order of the authorities and the emphatic (and deliberate) disorder of the demonstrators. The movements of the police follow a pattern (akin to the dance of the aerial-display teams), while the demonstrators’ explicit aim seems to be to use disorder and the disruption of the normal choreography of the street to gain control of it. The computer animation plays out a centuries-old battle: when Georges-Eugène Haussmann demolished the rabbit-warren lanes of the Parisian slums during the 1850 and 60s to build the city’s wide boulevards, it was with the specific purpose of creating an urban realm in which demonstration (and the building of barricades) would not easily flourish, and in which Napoleon III’s troops could be easily deployed to quell unrest.

The amorphous mass of disgruntled students and their supporters ended up contained in a neat police-lined cage for several hours. Tempers frayed and violence broke out. It would be seven hours before the demonstrators were allowed out

Watching Lagarde’s video recently I remembered how, in November 2010, through a neat bit of police choreography, I too was corralled at a demonstration. It happened while I was marching, alongside a thousand or so others, on London’s Whitehall to protest a rise in university fees in England. At a certain point, a solid line of police appeared in front of us, blocking our path. We turned around and began to make our way back towards our rallying point at Trafalgar Square. Another wall of helmeted officers began to form ahead of us. And behind them we could make out a clutch of their fully armoured, mounted colleagues. Panic began to ripple through the crowd. With a few others I dived down an unguarded alley, somewhere close to the South African High Commission and the Lord Moon pub. I escaped. And checking Twitter later it became clear that that escape had been a lucky one. The amorphous mass of disgruntled students and their supporters had ended up contained in a neat police-lined cage for several hours. As the day wore on, tempers frayed and violence broke out. Shaky mobile-phone footage documented examples of apparent police aggression, each social-media post eagerly picked up by news organisations. It would be seven hours before the last of the demonstrators were allowed to leave, by which time 41 arrests had been made and injuries sustained by individuals on both sides. Since the early 2010s the ethics of the so-called police ‘kettle’ tactic has caused much debate. In 2011 campaign group Liberty said it was having ‘a chilling effect on many people’s rights to freedom of expression and assembly’, and various reports make clear that the threat of kettling was a worry for all but the most hardened demonstrators (a cynic would say that this was precisely the police’s intention). In 2012, following legal action in the UK challenging kettling, it was deemed a lawful means of policing demonstrations. ‘Containment of a crowd involves a serious intrusion into the freedom of movement of the crowd,’ the judge warned in his ruling, noting that ‘it should only be adopted where it is reasonably believed that a breach of the peace is imminent and that no less intrusive crowd control operation will prevent the breach.’

It is this expression of power, in which political action by the people elicits violent state reaction, that plays out in several recent works of moving image, in which the politics are given less prominence than its spatial form

A demonstration, which the historian Eric Hobsbawm defines as ‘some physical action – marching, chanting slogans, singing – through which the merger of the individual in the mass, which is the essence of the collective experience, finds expression’, relies on those protesting taking control of a (usually public or semipublic) space to articulate, or appear to articulate, the will of the people (the demos). The ‘breach of the peace’ the judge refers to is in essence an undermining of state authority (the definition of breach of the peace under UK law is ‘against the peace of our Lady the Queen, her crown and dignity’), which the state’s enforcers, the police, must in turn counteract. But it is the presence of the police – modern crowd theory dictates – as much as any uniform philosophy that gives a demonstration its unity. The most up-to-date thinking among psychologists is that demonstrators retain their individual personalities (with their varying propensities to violence, illegal actions, desperation to escape, etc) but will unite when faced with a common, hostile force. ‘You didn’t lose your identity,’ the clinical psychologist Vaughan Bell notes of a demonstrator, ‘you gained a new one in reaction to a threat.’ The threat is not just of physical violence or arrest, but also that the crowd’s control of the street will be imperilled by the defensive actions of the police (a common chant of demonstrations globally is “Whose streets? Our streets!”). Speaking of her 2007 performance Tatlin’s Whisper #5 (2008), for which she employed two police officers on horseback to round up visitors in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall using established crowd-control techniques, Tania Bruguera noted that “mounted police is something you can see in the photos in 68. You can see it in 1935, 1968 and 2000, you know, so it’s a kind of historically recurrent image of power. And always linked to a very specific political action.” Indeed, it is this expression of power, in which political action by the people elicits violent state reaction, that plays out in several recent works of moving image, in which the politics or the motives behind a demonstration are given less prominence than its spatial form: the shape of the crowd and the area that crowd occupies.

Like Lagarde’s artwork, Greek artist Manolis D. Lemos’s video dusk and dawn look just the same (riot tourism) (2017) recalls a philosophical history stretching from the Commune of 1871, through to the student uprising of 1968, and the Reclaim the Streets and Occupy movements during the 1990s and 2000s (and, more obviously, the Greek antiausterity protests during the early 2010s), in that it examines how a group of people can enact a radical and antiauthoritarian agenda through their collective presence in a public space. The slow-motion video, recently shown at the New Museum Triennial in New York, opens with a group of 26 figures pictured from behind walking down the middle of an Athens street, all dressed in identical spray- painted overcoats. A rebetiko plays as soundtrack. This gang gets the occasional odd – perhaps even fearful – look from passersby. As the work progresses, the figures pick up pace, their speed again out of sync with the normal behaviour expected within this environment. As they arrive in Omonoia Square, a commercial district, tourist destination and site of those antiausterity demonstrations , the gang eventually fans out, weaving among taxis, their unpredictability co-opting this urban space as its own.

Containment is a weapon used by the police to neuter the unpredictability of demonstration tactics and the manner in which they seek to colonise space (as one blogger on a far-left activist forum bemoaned in 2011, after a particularly unsuccessful outing, ‘It is difficult to imagine anything quite so moronic as chanting “whose streets? Our streets!” inside a police kettle. If they are “our streets”, why aren’t we marching down them?’). The other option at the disposal of the police when presented with an unwanted crowd is dispersion. In Hiwa K’s 2011 film This Lemon Tastes of Apple the Iraqi artist documents a performance he made during a demonstration in the Kurdish city of Sulaymaniyah, through edited-together footage filmed by others present. Occupying a street en masse, demonstrators command attention through shouts, declamations and chants, their fellow protesters capturing the commotion by way of camera phone. Groups moving in opposite directions thread between each other. The video follows the artist and an accomplice, who, weaving their way through this throng, play Ennio Morricone’s melancholic refrain from the spaghetti western Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) on harmonica and guitar. The title of Hiwa K’s work (which has a political complexity far greater than my outline here) refers both to the aroma of apple said to have been given off by the poison gas that Saddam Hussein’s regime deployed in Kurdish settlements in 1988, and to the use of lemon to counteract the effects of teargas red against contemporary demonstrators by the armed forces of their own Kurdish regional government. The ring of teargas canisters and rubber bullets is heard midway through the six-minute lm; the crowd scatters, demonstrators escaping in all directions, some bleeding, others helping the wounded. To restore the order – and the predictability – of the streets, the authorities elected not to imprison the body of the demonstration, but to destroy it. Of course, given that one aim of a protest action is spectacle, this could have back red, police aggression often only raising the visibility of a protest in the media (both social and traditional).

In this haunting work the sound of the crowd and sirens gives way to the lonesome gure of Lee Han-yeol, a man in his twenties who explains the circumstances of his death, killed after being hit by a gas canister

The violence present in This Lemon Tastes of Apple is taken to its logical conclusion in Kurdish artist Ahmet Öğüt’s United (2016–17). An animation in the style of Korean manhwa, the opening scenes follow the arc of several canisters of teargas red at a protest in Seoul. In this haunting work the sound of the crowd and sirens gives way to the lonesome figure of Lee Han-yeol, a man in his twenties who explains the circumstances of his death, killed after being hit by a gas canister while taking part in the June Struggle of 1987, the movement for democracy that formed after the South Korean military dicta- tor Chun Doo-hwan unilaterally nominated a successor. The video returns to another street battle but this time in the Turkish city of Diyarbakır (where Öğüt was born). Teargas has again obliterated a demonstration, claiming another victim. The animated avatar of eight-year-old Enes Ata, who attended a demonstration in March 2006, describes his death and how a gas canister had fatally hit him also. Both occupations of the public realm that Lee and Ata participated in threatened the state authorities, and both were the victim of fatal retaliation. United was originally commissioned for the Gwangju Biennale in 2016, an exhibition founded to commemorate the Korean democracy movement, where it was exhibited on a vast video-display board overlooking a crossroads in the Korean city; in choosing this site for the video, Ögüt neatly takes back a small slice of the urban environment on behalf of the two victims.

As much as these works occur during a moment of reengagement with demonstration internationally, they also mark the end of the demonstration as a merely physical form. While the artists discussed here illustrate the visual power of street protest, they also reveal its limitations, showing how easily the state can contain or disperse the voice of the demonstrations. It is striking in this regard that the demonstrations of the Arab Spring were characterised by constant mediation (in his 2012 performative lecture, Pixelated Revolution, artist Rabih Mroué details how activists had posted extensive instructions online for how demonstrations should be filmed and photographed for maximum effect on social media); no demonstration would be deemed successful today if it did not garner viral coverage. While in the simulated protest presented in Déploiements the protesters are waving placards, This Lemon Tastes of Apple demonstrates that they would be more likely to be holding their phones aloft. The co-option of online attention has become as important as the occupation of physical space, giving rise (for better or worse) to global conversations over localised battles. Indeed, the most vocal protester movement of 2018 has not been enacted through marches and megaphones, but through the digital force of #MeToo. It is, after all, hard to kettle a hashtag.

From the May 2018 issue of ArtReview