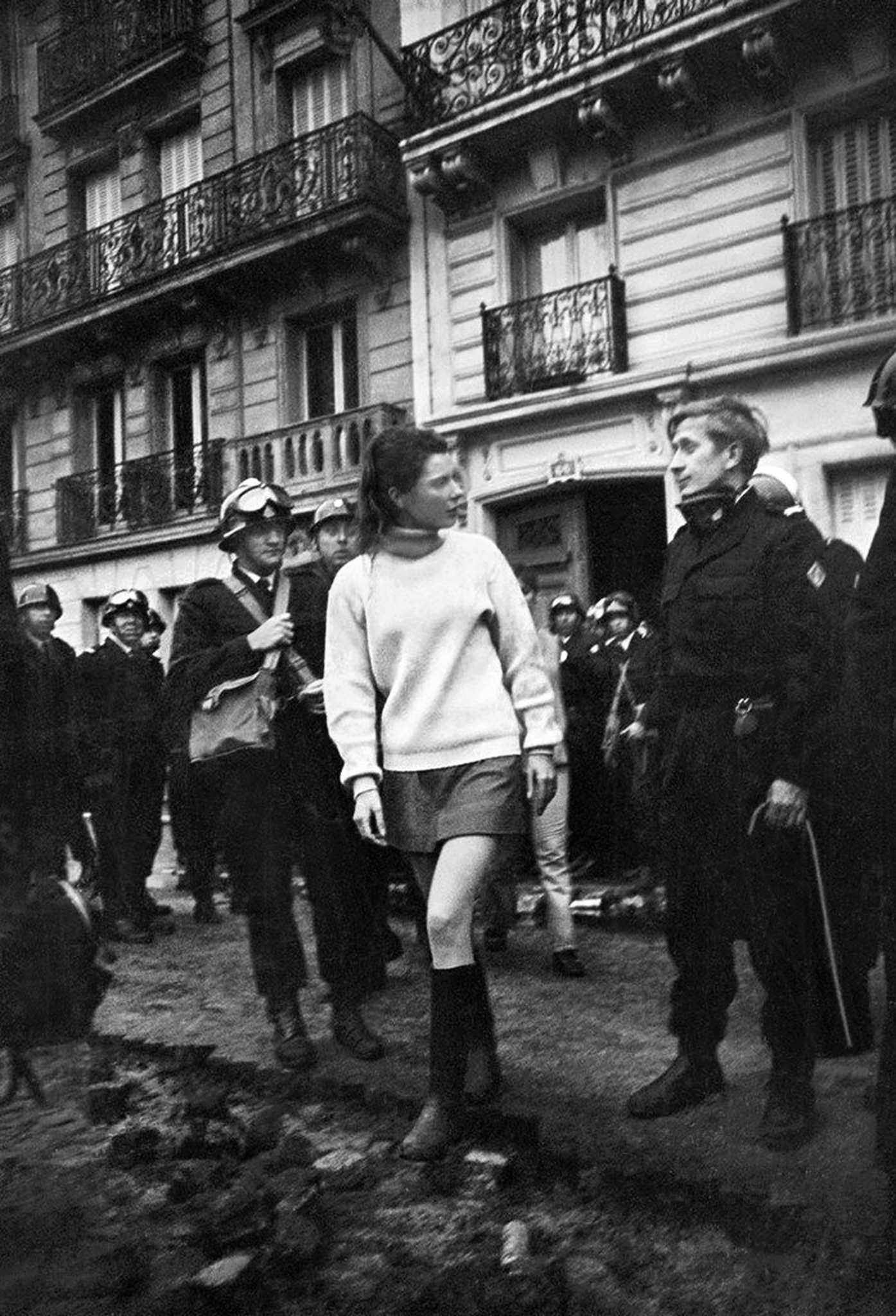

I experienced the événements in a slightly schizophrenic way, since it was enough to step out into the street to smell the tear gas. In 1968, I was living with Daniel Templon in a bedsit in Rue Bonaparte. Daniel and I were out almost every night in the streets. But not having any experience of student life, neither of us felt particularly involved in the movement, nor did we connect much with the students’ demands. I didn’t throw any paving stones. The only thing I had in common with the demonstrators was youth and energy, and with my generation, a very liberated approach to sexuality. Daniel and I practiced free love, without qualms.

If we consider the immediate impact of May 68 on art production, I’d argue that nothing much happened. But 68 provoked a reform of art education. It wasn’t so much a revolt against academicism, since many of the artists who were getting recognition at the time hadn’t studied at the Beaux Arts in the first place, yet after 1968, art schools started admitting young, radical artists as teachers. It’s paradoxical, but I think the post-May 68 generations went to art school much more spontaneously than their predecessors.

I firmly believe that an artwork should, first and foremost, be about making ideas. Before making money! … Sadly, today’s artworld is marked by a profound shift; the majority of contemporary artists are caught in the nets of a speculative market, and some of them are willing to play by those rules. But today’s globalised artworld, with its openness to a diversity of artistic practices could also be seen as a more or less distant consequence of the open-mindedness of 1968.

Attitudes are more open than they once were but, compared to our ways in 1968, it seems the playful element has somehow withered out; as for sexual freedom, it has only gone backwards since then. I feel like this spirit of openness is under threat nowadays. The May 1968 generation, those for whom it was ‘interdit d’interdire’ [‘forbidden to forbid’], can see censorship resurfacing here and there.

Censorship has today taken the shape of a certain brand of feminism. But we need to stop entrapping women into the role of the victim. That’s what’s happening lately, in the wake of the Weinstein scandal. I am astonished to read testimonies by women who claim they have been the victims of men. How so? Are they paralysed? Stupid? They don’t seem to know how to react in a way that strikes me as elementary. All of this nurtures the idea of women as eternal victims. I can understand that a woman working in a factory, whose job depends on an overbearing foreman, doesn’t dare speak out; but I find it harder to believe that a university student can’t stand up to their professor. A woman today must have the education and strength to fight back.

Sometimes, young people strike me as being much more serious, much more conformist, generally speaking. They have their reasons: we are the children of consumer society, we never had to experience unemployment, or face up to AIDS! Having said that, I still believe that morality should be able to free itself from contingencies.

This text is an abridged translation of a article originally published in French in Femmes et Filles. Mai 68, Éditions de l’Herne © Éditions de l’Herne, 2018

From the May 2018 issue of ArtReview