What really happened? As it’s always been with the great private investigators, this is the question that drives the ‘cases’ dealt with by Forensic Architecture in its ‘counter investigations’. The research agency, based at London’s Goldsmiths and led by architect and theorist Eyal Weizman, has made it its business over the past decade to take on states and politicians who habitually deny documentary evidence – of unlawful killings, unacknowledged drone strikes and other state-initiated violence – presented by journalists, political activists and citizens. If ‘plausible deniability’ has become part-and-parcel of politics in an era of the ubiquitous digital-mediation of events, then what Forensic Architecture attempts is to up the ante on how the documentary record affirms ‘what really happened’, through the use of advanced digital techniques of spatial reconstruction and simulation, cross-referenced with multiple, often crowd-gathered and open-source information: CCTV, TV journalism, camera-phone footage, satellite maps, etc.

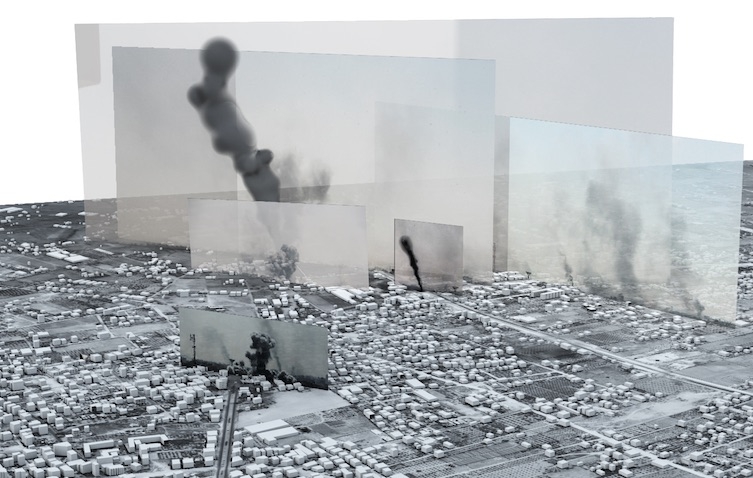

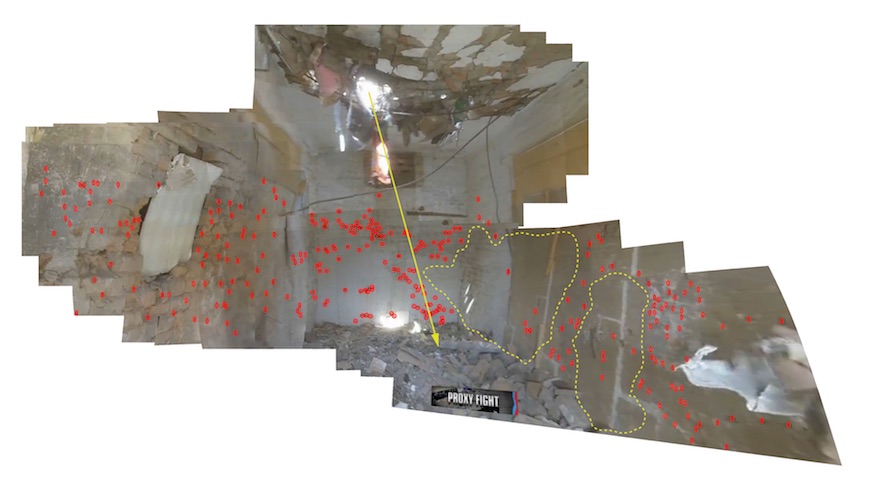

A typical case is Drone Strike in Miranshah North Waziristan, 30 March 2012 (investigation 2013–16). For years, the Bush and then Obama administrations had refused to acknowledge their campaign of drone strikes in northern Pakistan bordering Afghanistan. Here we’re presented with 42 seconds of video footage of a ruined domestic building, seen from a higher adjacent window, then footage inside the battered space, with a hole in the concrete ceiling and shrapnel marks across the walls. The female voiceover takes us through how these frames are mapped onto a computer model – a sort of collage of overlapping image surfaces, checked against satellite views of Miranshah’s streets. Inside, the pattern of shrapnel marks is analysed to suggest the point of detonation – midair in the room – while the areas free of marks suggest the outline of where the human victims must have been standing, the room’s walls ‘exposed to the blast like a film is exposed to light’, the narrator suggests, her tone dispassionately objective. From all this, the conclusion is of the use of a building-piercing Hellfire missile, a weapon only the US could have deployed.

Is this still conjecture, or beyond reasonable doubt? The problem of inference, of uncertainty, shadows Forensic Architecture’s investigations. The most bitterly fought case here is also the visual centrepiece of the ICA show, the huge information-wall, timeline and floor map that contests The Murder of Halit Yozgat, Kassel, Germany, 6 April 2006 (investigation 2016–). A significant presence in last year’s Documenta 14, the work took up a long-running controversy over a series of murders of local Turkish shop owners, initially attributed by state authorities to Turkish gangs, but ultimately to the neo-Nazi terrorist group the National Socialist Underground (NSU). The Murder of Halit Yozgat… however addresses inconsistencies in the testimony of Andreas Temme, a security agent for the state of Hessen, who was at the Internet café in Kassel that Yozgat managed, around the time he was shot dead. As Weizman put it to The Intercept, ‘We’re trying to demonstrate that his statements are questionable enough that the files need to be opened’. The work succeeded in reigniting the debate over an investigation that was mired in secrecy and obfuscation among local and national politicians and security agencies regarding what those agencies knew about the NSU, and how their agents managed informant sources among Germany’s neo-Nazi groups.

what we are presented with here is a celebration of a technique, and the affirmative spectacle of political agency reclaimed through the mastery of technology

Forensic Architecture’s sophisticated and intensive projects have taken shape at a time when human rights organisations, independent activist networks and NGOs increasingly assume the role of challengers to official narratives, or to official attempts to suppress counternarratives. Institutionally, the group’s activity is indicative of how both academic and curatorial cultures have become entwined in this wider shift in the locus of political activism, with the art gallery becoming just another channel of dissemination for this broader political culture of independent and quasi-institutional activism.

But there are political limits to that culture. The ICA show presents a range of subjects – from the gratuitous shooting of two Palestinian teenagers in the Gaza Strip by Israeli soldiers, to the Israeli bombing of the city of Rafah in Gaza, to the disappearance of Mexican student protesters (in The Enforced Disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa Students in Iguala, Mexico, 26–27 September 2014) to the mapping of the Mediterranean calamity of drowning migrants and EU officialdom’s furtive denial of the consequences of its policies (in The Left-to-die boat, Central Mediterranean Sea, 27 March 2011, investigation 2012). The political perspective of Counter Investigations is that of a generalised denunciation of human rights abuses across the world, driven by the assumption that if only irrefutable evidence were presented to the world and if state power could be made more accountable, greater justice would prevail.

In an art gallery presentation, it raises the question of what is being proved, and to whom

Forensic Architecture’s techniques of presentation – the vast infographic boards of timelines, the sophisticated video simulations, models and data visualisations – are attempts at cohering dense combinations of information. But they also produce their own aesthetics, the aesthetics of objectivity, which, ironically, has the goal of persuading us of its objectivity. Forensic Architecture is well aware of this irony, noting in an accompanying text that the legal tradition of establishing truth often relies on performative techniques of persuasion that are never entirely objective. But in this gallery presentation, it raises the question of what is being proved, and to whom. After all, it doesn’t take Forensic Architecture to reveal to an audience of liberal-minded gallerygoers that there are innumerable injustices around the world. If the agency’s campaigns have already yielded their results in the public sphere, then what we are presented with here is a celebration of a technique, and the affirmative spectacle of political agency reclaimed through the mastery of technology, along with the vicarious feeling of political participation.

For all its display of truth-telling technique, Counter Investigations is not a place for deliberating bigger political ‘truths’. How we respond to the catastrophe of the migrant crisis, for example, or to conflict in the Middle East, are big political questions with no easy answers. Beyond the endless stream of particular injustices and abuses, they require us to develop much bigger pictures of what is ‘really’ happening.

Counter Investigations: Forensic Architecture, ICA, London, 7 March – 13 May

From the May 2018 issue of ArtReview