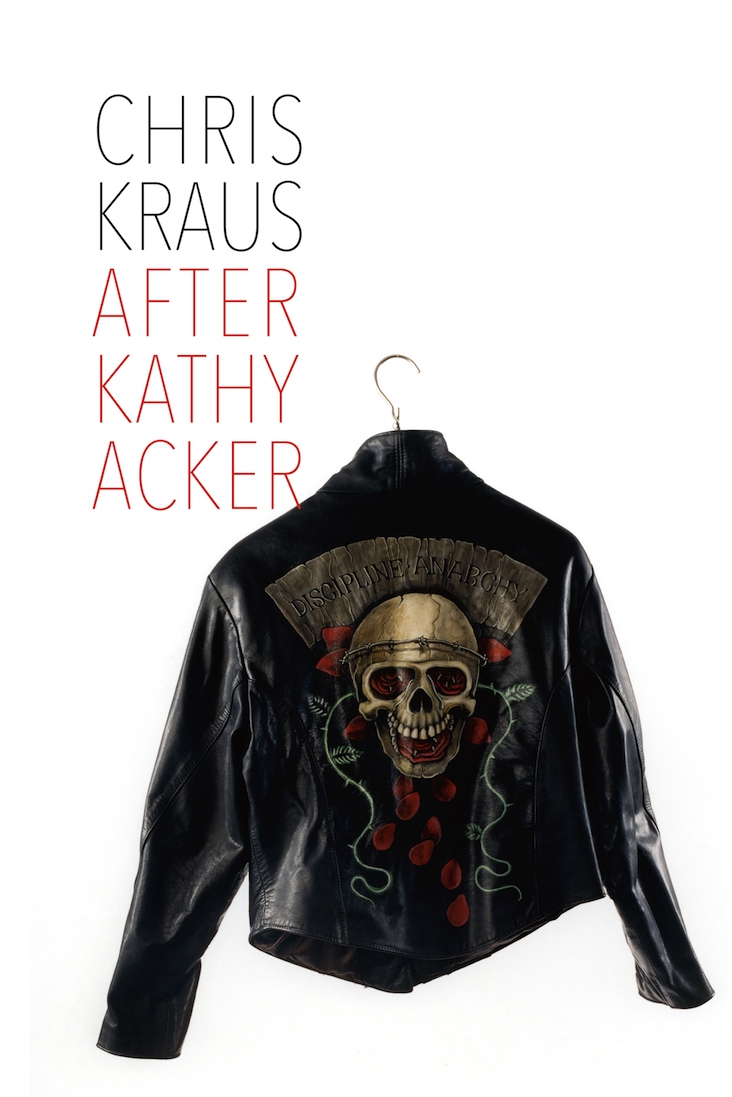

After Kathy Acker draws together the work of two writers who carved out singular spaces for themselves in experimental literature. Chris Kraus, a star in the bright firmament of today’s autofiction writers, and best known for I Love Dick (1997), here writes a lucid, revealing biography of her iconic forebear, the late Kathy Acker. A highly transgressive, postmodern figure, Acker is notorious for her piracy of other writers’ work; for her prose, which, by turns abrasive and girlish, drew on her experiences of family psychodrama, sex work, BDSM and illness; and for her image – a punkish downtown celebrity with tattoos, piercings and, later, a motorcycle. Importantly, according to Kraus’s analysis, Acker is also the first woman to seek and attain the ‘iconic status of Great Writer as Counter Cultural Hero’ (in this sense, then, female writers in a certain tradition will always be ‘After Kathy Acker’). She did this, Kraus suggests, by writing from a nonnaturalistic, psychic space and by excluding all viewpoints aside from her own. In other words, it’s Acker’s formidable focus on herself in all its possible manifestations that allows the reader to navigate a torrent of Burroughsian cutup and personal prose, and which also serves to elevate her to stardom.

For the most part, Kraus maintains a careful even-handedness, reflected in a dominant prose style that distances itself from her own works that have explored slippery disclosure and mutable selfhood. We read that Acker ‘enjoyed an affair’ here or there, or that friends are ‘keen to introduce her’ to people, a sometimes-formal tone that strikingly contrasts with Acker’s visceral language of batshit all-caps, erratic grammar and a committed approach to the word ‘cunt’. Kraus’s journalistic coolness also steadies a journey through some thrillingly salacious content involving a cast of well-known figures from art, theory and literature. We’re party to Acker’s hot pursuit of Dan Graham, to her affairs with Len Neufeld (partner of Martha Rosler), Peter Wollen (partner of Laura Mulvey) and a host of others, and to her dramatic fallings-out with friends and peers. It is a strategy that deftly allows the younger writer to extricate herself from the narrative, which includes a shared milieu (most prominently, Acker and Kraus were both involved with Sylvère Lotringer of Semiotext(e), though only Acker’s affair with him is discussed). It works beautifully, in any case: using tweezerlike precision in displaying her research materials and interviews, Kraus builds a questioning picture of a life, necessary for a subject who treated her own biography as a work of fiction. Kraus, indeed, is largely sympathetic to this self-mythologising aspect of writing, though there are clearly places she draws a line, and occasionally laces her comments with judgement.

Elegantly summing up the queasy bargains that art made with celebrity during a particular period, for example, Kraus dissects the lasting impressions made by Acker in an episode of ITV’s The South Bank Show, presented by Melvyn Bragg, which was devoted to the writer in 1984. Acker wears an ‘improbable long Comme des Garçons white linen tunic’ and heavily kohl-lined eyes as she points to the poverty of a building in her Lower East Side neighbourhood, describing the ‘junk trade’, ‘murders’ and other scenes of squalor. This image, Kraus points out, ‘juxtaposes the aspirational glamour of mid-’80s alternative culture with scenes of the unreconstructed underclass misery that became a ubiquitous backdrop to the Bush/Thatcher years… holding a mirror to her mirrors’. In Kraus’s telling, it will be this period that consolidates her fame, and it will be this particular brand of fame that will cause her work to suffer. She quotes Burroughs: ‘Involvement with his own image can be fatal to a writer.’

In fact, by the time I was studying literature in the UK the early 2000s, Acker had been canonised within British academia, a reflection of the UK’s particular embrace and augmentation of her avant-garde celebrity. The writing remains shocking, I found on revisiting, particularly in the way Acker ferociously applies the literary cutup. In Great Expectations (1982), scenes of soldiers raping on a battlefield canter through with commas to a Freudian family drama scene in which the protagonist’s ‘I’ appears from nowhere: ‘she sleeps she purrs her open palm on her forehead to his shudder trot, the clouded moon turns his naked arm green, his panting a gurgling that indicates rape sweat dripping off his bare strong chest wakes the young girl up, I walked into my parents’ bedroom opened their bathroom door don’t know why I did it, my father was standing naked over the toilet, I’ve never seen him naked I’m shocked’. In fact, Kraus’s closest and most admiring analysis of Acker’s writing relates to her inventive use of punctuation in Great Expectations, and the way that she uses colons to amplify thought: ‘the colon functions as a slap, a jolt, an epinephrine shot that yanks the sentence – and by extension, us – from grief’s downward drift into the present time’. It’s a grammatical device that stands in for Acker’s pushy rawness, and her drive to enter uncharted territories. It’s also indicative of Kraus’s care with this book, in which she has conscientiously paid attention to every way a writer’s life can be read, down to two dots. No mean feat, given that Acker was quite the piece of work, in all senses.

After Kathy Acker, by Chris Kraus, The MIT Press, $24.95 (hardcover)

From the October 2017 issue of ArtReview