Editor’s note: this article first appeared in the October 2017 issue of ArtReview and is being republished on the occasion of Jacqueline de Jong’s retrospective, Pinball Wizard, at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 9 February – 18 August 2019. De Jong was a member of the Situationists, and the founder and editor of the journal The Situationist Times (1962–64).

The artist Tino Sehgal once asked me what I was working on. “A small book called 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International,” I said. “May there be 50 years more!” he replied. That’s the spirit, I thought. Perhaps, when the Situationists have been fully absorbed into the totality of the spectacle, the ground will be cleared for a renewal of the avant-garde ambition to remake the world.

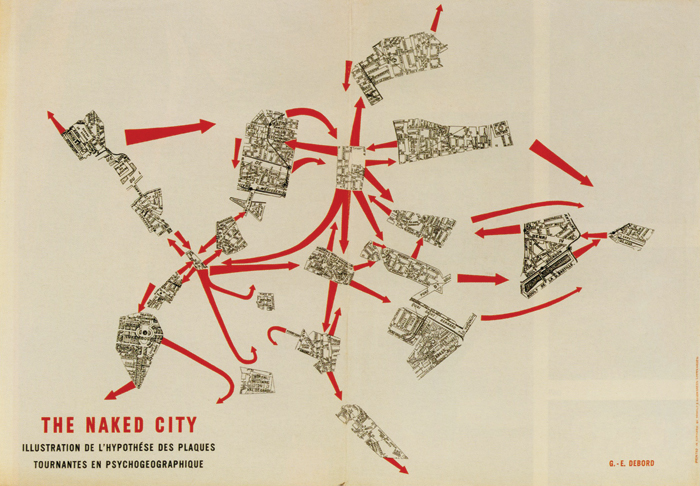

I was in Las Vegas recently, so naturally I went for a walk. It turns out to be a hard city in which to practise the ancient situationist art of the dérive. I started on the Strip, and soon discovered how thoroughly weaponised the urge to wander is in this most advanced centre of industrialised play. There’s no turn you can take that does not fold you back towards the bars and the slots. I had more luck on the edge of town, where the desert dust blows over the fenced-off driveways of abandoned motels.

It’s getting hard to wander, and yet it’s become something of a mainstream art, in the writings of Will Self, for example. But I’m encouraged by those like Stewart Home, Laura Oldfield Ford, Tina Richardson, Phil Smith and many others who keep dérive alive at the edge between art and everyday life. But perhaps it’s an oldworld pursuit, not suited for the contemporary megalopolis. Non-Western cities might need another practice to unlock the secrets of another city for another life.

The practice of dérive is supposed to lead to the theory and practice of unitary urbanism, which would be a built form without private property, capitalist relations of production and the division of work and leisure. Rather than abolishing work, the current stage of commodification has abolished leisure. The cell phone is an instrument of extracting value not only from labour but also nonlabour. Everywhere you go, everything you do with it generates data to be harvested and momentised by some corporation or other. The world we live in is the dialectical negation of Constant Nieuwenhuys’s New Babylon (1956–74), the highpoint of Marxist-Situationist urban utopianism. In models, maps and drawings, Constant imagined megacities for nomadic play. Only in fiction do I think you find work that dares to imagine a whole new built form at planetary scale, in Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy (1993–6), for example.

Guy Debord thought the diffuse spectacle had given way to an integrated spectacle by the 1970s, which folded the secrecy and industrialised corruption of the Soviet concentrated spectacle into its Western double. Now I think we would have to conceive of a spectacle of disintegration, in which the spectacle’s principle of the separation of being from having, and then of having from appearing, constructs a world in which even the ruling class can no longer know itself or the world it once conquered. Now it feeds on its own fragmentation and waste products.

For a while it looked like the situationist practice of détournement could break through separation and restore to creative labour the possibility of a communism of collective aesthetic self-making. One by one, media forms escaped from the grip of private property. But the ruling class regrouped at a higher level of abstraction. What was once the culture industry finds itself subsumed under the vulture industry, which no longer cares much who owns the content of the spectacle but rather who owns the vector along which information moves.

Once, we were all data punks: here’s three gigabytes, now form your radical media-art collective. Now we have to be meta-data punks. Our struggle is to socialise not the media content but the form, as my comrades at memoryoftheworld.org have grasped. Here it is worth remembering that the Situationists before us were also careful archivists, but in that domain their practice was very conventional, and gave up many hostages to the archive-industrial complex.

The medium in which all avant-gardes work is never really art. It is always media. The Situationist International may have been the last avant-garde whose media strategy included the production of forms of novelty that created visibility. The Futurists, Dadaists and Surrealists had all played this game before, as Fluxus did alongside them. But the Situationists were perhaps the first to appear by way of negation, by refusing to appear. It’s a tactic absorbed into the very name of entities like the anonymous collective known as The Invisible Committee of more recent times.

The later work of Debord and Alice Becker-Ho takes this a bit further, with what, to borrow a phrase from Debord, we might call the devil’s party. Perhaps the avant-garde of today would refuse any visibility, or appear only so as to convey coded messages to each other. Mediation might remain the consistent plane of attack of the avant-garde in the disintegrating spectacle, but no longer to appear in it, even in negative.

There’s no shortage of relatively neglected work by Situationists and former Situationists that bears working through in the current spectacle of disintegration. René Viénet stood aside from the fascination with Maoism on the French left. His extraordinary film Peking Duck Soup (1977) tracks China’s Communist Party as a distinctive form of spectacular ruling class. Given how integral China became to the global spectacle of disintegration, it bears up rather well.

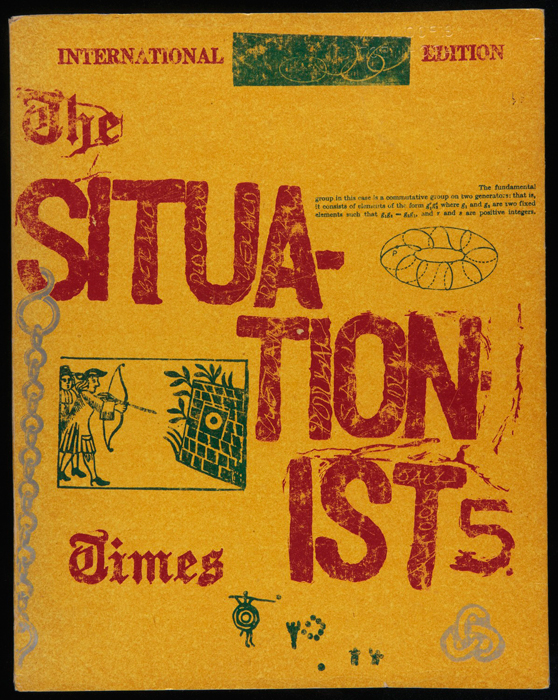

Asger Jorn and Jacqueline de Jong spent a considerable amount of time trying to find ways to diagram the possibilities of situations. Her journal The Situationist Times is a remarkable and multilingual attempt to imagine what forms of organisation might be after the decline of centralised and hierarchical forms, but without being too utopian about distributed forms of order.

That Michèle Bernstein’s détournement of the novel, All the Kings Horses (1960), was published in English by Semiotext(e) seems appropriate, given the way that house became its own kind of diffuse, acephalic avant-garde, one finally prepared to speak frankly about certain domestic matters on which the Situationists were notoriously silent. Those who talk theory without copping to who and how they fuck, what and how they get paid, how the little art-and-lit-world industries on which they depend really function, speak with a corpse in their mouth.

That the Situationist International mostly kept the institutions of art, media and academy at arm’s length, particularly during its ‘political’ phase, tends to mask the extent to which it always relied on patrons. But there is something contemporary in its ambiguous working of the margin between commodification and precarity. Many of those in the Parisian milieu from which the Situationists in part emerged were children of the war. They had already experienced the failure of middle-class family life before it had become a sanctified postwar ‘lifestyle’. Some among them were fuckups, loafers, addicts, sex workers. They anticipate those who today live among the ruins of the neoliberal war against us, remote from any official artworld, but doing the most interesting things, never the less, and out of sheer necessity.

During the May ’68 events in Paris, the Situationists decamped to the Committee to Maintain the Occupations, and did their best to maintain communication between the students and striking factory workers. They had already identified the subjects of postwar mass higher-education as future proletarians, but of a novel kind: able to buy some consumer goods with their middle-class income should they be lucky enough to get jobs, but paid in the debased currency of mere things and separated from the capacity to act in and on the world.

Debord did not see May ’68 as a unique event but part of an endless cycle of irruptions of historical time into the fashion cycle of spectacular time. It would not have surprised him that these continue to happen, whether in the form of Tiananmen Square or Occupy or the so-called movements of the squares. Boredom breaks through the skin of the spectacle of disintegration as regularly now as cyclones. One of Debord’s texts from the 1970s diagnosed a sick planet: on the one hand shrouded in the clingfilm of spectacle; on the other hand unable to integrate into its false totality its two great externalities – pollution and the proletariat. The historical impasse diagnosed by the Situationist International remains, even as their strategies against it pass into and are recuperated by that history. Avantgardes are made to die in the war of time.

McKenzie Wark is professor of media and cultural studies at The New School, New York. He is the author of The Hacker Manifesto (2006) and a number of books exploring the history and legacy of the Situationist International. His General Intellects: Twenty- One Thinkers for the Twenty-First Century was published in 2017

From the October 2017 issue of ArtReview