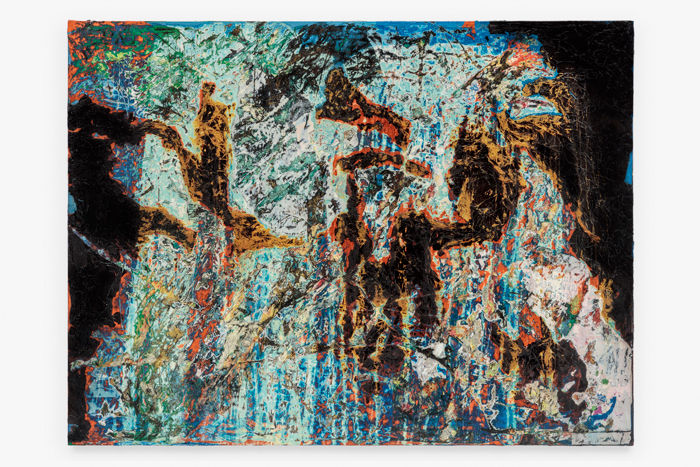

ArtReview caught up with Los Angeles-based artist Mark Bradford in Shanghai at the launch of an exhibition titled Los Angeles, a ten-year survey of his painting, sculpture and videowork at the Long Museum, West Bund. It includes largescale sculptures such as Mithra (2008), an arklike structure created for Prospect.1 in New Orleans as a sign of potential renewal in the wake of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina, and a new series of paintings referencing the Watts Rebellion, which took place in Los Angeles in 1965. While many of the works draw on the particular conditions of the urban experience in the US, other works respond specifically to the Long Museum’s industrial architecture or, in the case of a series of suspended globes (in which the African continent holds a more dominant position than it does in traditional projections), look to a wider perspective. Beyond his own creative production, Bradford cofounded the LA-based nonprofit Art + Practice, in 2013, which is a hybrid exhibition space and social services centre for young adults who are on the point of exiting the foster-care system. In 2017, as part of his presentation at the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, he included a training programme for local prisoners.

Back in Shanghai it is July and the city is at its hottest and most humid. Even the coolest of cucumbers is sweating, and the flowers that marked the exhibition’s opening the night before are starting to wilt.

ArtReview There’s a big sign outside this museum…

Mark Bradford …that says ‘Los Angeles’.

AR I think that there is something very architectural, perhaps more specifically urban, about the surface and skin of your paintings.

MB Yes, which I’ve always been kind of obsessed with: architecture, skin, grids, repetition.

AR Are you conscious of an audience here in Shanghai that might not be familiar with LA, that might not speak English and not be able to piece together the context for some of the works?

MB I’d say that they would probably be less familiar with the complexity of African-American culture, because everyone has some form of YouTube or WeChat or Instagram, so unfortunately we’re broadcasting stereotypes all over the world. People are like, “Oh, I know you!” It’s horrible. It’s just shameless, right? I think it’s actually doing us a disservice in some ways. People saying, “Oh, I know. I’ve seen you on YouTube. I’ve seen you on Instagram. I’ve seen you on Vine.” And I’m like, “OK. Wow, all right.”

AR Are you conscious then about the focus being on your person – your height, your being an African American in China – as much as your art?

MB In this instance, I made a T-shirt that said, ‘Yes, I am two metres, seven centimetres’ [in Chinese and on sale in the gift shop]. Every once in a while, I decide to play with it. Sometimes I’ll just say, “I don’t feel like being an object. I think I’ll be a subject playing with an object.” It’s not going away. It comes up in almost every article – they just comment on my physicality. What I hope comes through is a reaction like, “Huh? OK, this is not the blackness that I’m familiar with”. That’s all you want: plurality.

AR That is the interesting thing about having a place as the title of the show – and I mean, more specifically, a place that is not where the show is – because it already embeds a context as a subject matter that is not about your identity.

MB That’s what I wanted to do.

AR Is that something that’s a struggle these days?

MB No. I think that me and the things that I’m interested in, and Mark Bradford, are two separate conversations. What I really try to do is be very straightforward about the things I’m interested in and very clear when I’m talking.

AR What are you interested in now?

MB I’m interested in public education. If we look at the practitioners in the artworld and what schools they come from, are we developing practitioners from state schools that come out of university owing a modest amount? Or are we constantly going back to the Ivy Leagues? I’m fascinated by that. I’ve been doing a lot more work than just with state schools. Because if we’re asking different questions, but we’re still going to the same groups, isn’t that a way that economic and power hierarchies are built in? There are very few African-American gallery directors. There are certain things that are just built-in, and so on a social level, it’s something I’m fascinated by.

AR How do you feel when you look back at an older work? Do you ever wonder, “What was I thinking at the time?” Or is it always clear that you knew exactly where you were and what you were thinking?

MB I would say that all the works are like a relationship. I do the best I can when I’m in it. And when I’m out of it, I look back, and I’m like, “Well, I could have done a little better”.

AR Do you ever do that?

MB Go back and reenter it? No, when it’s done, it’s done. I really know and understand that I can control what’s in my studio. I do know that. I can’t control a lot of stuff – less and less, actually – but I sure as hell can control that. Nobody gets to my studio, not a gallery, not a collector, no one is telling me what to do. I do that. I decide.

AR How accepting of letting go are you once a work has left the studio?

MB You have to let it go. Some artists get crazy with it, but you have to let it go. I think that if you’ve done everything that you can, and you’ve answered everything that you can, then you should be able to let it go. There’s nothing more that I could do. My maturity level is not the same as it was 20 years ago, but 20 years ago, I did the best that I could at that level. I’ve grown. I can look at my own work and I can see the growth.

AR How effective do you think art can be as a vehicle for commenting on social, political, racial issues?

MB That’s a real slippery slope. At the end of the day, it’s just a painting. I’m very clear it’s a painting. You can construct things around it. There are much more direct ways of dealing with activist work.

AR You tend to do a bit of both.

“Los Angeles is a myth that’s lodged in our collective memory. It’s nowhere and everywhere”

MB I blur it. But then it’s always been blurred for me, because if I keep my mouth shut, maybe nobody’s going to pick up that I’m gay, but I’m always going to be black. There can be no, “I’m just an artist in the world”, it’s impossible. As soon as I step outside, I see the police, they see me, and they drive in the back of my car really fast and check me. I’m aware that the black body is always political. Blurring is the easiest thing in the world for me.

AR Sometimes it feels that art is always doomed to stop at representation, both literally and in terms of society, rather than going directly to the heart of any problems it might seek to tackle.

MB You know what, I always stayed away from representation because I just wasn’t comfortable representing anything. I don’t think anything’s a model, that’s my problem. Saying something like, “I will represent black culture” – that’s a model.

AR Do you get to choose to represent that or do other people choose that for you?

MB They try to choose it for me, but I have developed a practice for me that gives me space, that’s all. It’s ‘Los Angeles’, but it’s not Los Angeles – it’s my version of whatever I think it is.

AR What do you think Los Angeles is?

MB Los Angeles is a myth that’s lodged in our collective memory. It’s nowhere and everywhere. It’s that California sunshine – ‘Hollywood’. I love how in the artworld they’re always saying, “LA is the place, LA is the place. Everyone is moving there.” But LA has always been the same. It’s manufactured. It’s very dystopian. It’s almost a new Las Vegas.

AR I always think of Las Vegas as an extension of LA because so many of my friends keep ‘popping’ over there for the weekend.

MB Totally. And I’m comfortable in a place that eats its young. I like those spaces that are wilder.

AR Do you think those kinds of spaces are still going to be wild or do you think they get better known and the wildness stops?

MB Well, do you know what happens now? There are these ‘alternative sites’ or ‘underground sites’, but nothing lasts for more than 24 hours before somebody discovers it, uploads it to Instagram and it becomes a ‘thing’. There are no weird spaces because we all have these communication devices. You know what I think is going to happen? I think people are going to turn back and say, “You know what? We’ve had enough of that.” Those little hashtags are getting a little tired.

AR Do you tend to experience places by car, by foot?

MB Both. A car if I’m seeing how things have changed in general. And if I really need to micro, I’ll stop and walk so I can really look, and think like, “What was here before? Yes, it was that. Oh, that’s interesting. I haven’t seen this before.” New companies pop up because the need is always there. It’s just basically some type of parasitic lender or some parasitic company. If a company says, ‘We will get rid of bedbugs in 24 hours’, you know the bedbugs are already there. Or, ‘We will buy your home, fast cash in 24 hours’ – they already know you’re losing your home. The biggest one – now that we’ve gone through the bedbugs and we’ve gone through the quick loans, divorce and custody – that I see now is car title loans in ‘five minutes or less’.

AR I was thinking of LA as a place of circulation.

MB It’s not, it’s very segregated. The freeways are the cutoff for race and economics. The West and North are more affluent. In the South and East it becomes much more mixed, more working class. There are some affluent pockets, of course.

AR In his 1971 book on LA, the architecture critic Reyner Banham has a great passage where he talks about how coming off the freeway is the transition between private and public space, because that’s where a woman starts to apply her makeup.

MB That’s great. That’s exactly where I am. I’ve seen much more culture, and more emigration in my neighbourhood. I see street vendors more, I see policing more. You just see it more. You optically see it more.

AR Do you try and take that way of seeing into the paintings?

MB I think it seeps in.

AR I think there’s a way that your paintings present themselves as a complete whole that then gets atomised the more you look at it, into gestures or signs…

MB Yes. I take material from social things like that, but you know what else I think I do? I try to take it from somewhere and then I try to scrub it as if nobody’s going to know where I got it from. It’s silly, right? It’s like a palimpsest. I guess I don’t know why I do that, I just do. Who cares where it came from?

AR Do you see yourself as part of the continuum of this ever-growing palimpsest? That at some point, people see your work and contextualise it completely differently, and it becomes part of a different story?

MB Yes. It seems like I’ve been a part of two or three stories thus far. It seems like I’ve been ‘the hairdresser’, and then I was ‘the urban kind of person’, and then I’ve become ‘the Jackson Pollock of our age’ [a headline for an Artnet.com report on Bradford’s project for the US Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale]. But that stuff just doesn’t touch me.

AR You can’t control it.

MB No, you can’t control it. That stuff just stays out of the studio. It really does. I’ve always been a reader. I’ve always been very curious, and I tend to follow whatever I’m interested in and I do a lot of research. I just kind of do that.

AR Why did you become interested in visual arts generally, and painting specifically?

“When the art teacher was talking, I actually understood what he was saying and I was engaged. I thought, ‘Oh, this has never happened.’”

MB Why did I do visual arts? It never was this lightning-bolt thing. I never really thought of myself as being an artist. When you come from a working-class family, you don’t think of being an artist as something to make money at, especially if your mother is a merchant. Well, you know what, my mom was a hairdresser and I was a hairdresser. She was like, “Look, you’ve got to have a gig to make money. I guess your gig is hair. So do whatever you want.” In some ways, it was kind of freeing. I always felt like I could do whatever I want.

But being a visual artist, I always knew I needed something that I could do every day. I knew I’d like to have a studio practice. I like going to a site, and that might come out of being a stylist. You get into your car, you go to a place, you open shop. There’s a part of me that likes that.

I’m really a shopkeeper. I knew I wanted something studio-based, not poststudio.

Other than that, and going to clubs, travelling and working in a hair salon, it’s like art was the only thing that held my interest. When I started taking classes at the community college it was the only class that I passed and would show up for. Because I had a very long history, from sixth grade until I sort of graduated, of not showing up, not finishing the papers, being in the back – I was that boy.

I was surprised that in art class I sat in the front. When the teacher was talking, I actually understood what he was saying and I was engaged. I thought, “Oh, this has never happened.” I’ll take another class, and another one. Then I looked up and I said, “Well, I’ll be damned, I’ve finished a whole semester – with decent grades”. That was unheard of. I would study, and I was like, “Oh, wait a minute, this is a whole new me”. So really, it was just incremental.

Then somewhere along the line I said, “I’ll be damned, maybe I’m an artist”. But that was a really small voice, because I was still going to clubs and still working in the hair salon. I was really basically going to the community college. Everything was slow. I bumped into myself. I wasn’t one of those people that just knew what they wanted to be. I bumped into it. Even though the signs were always there. I was always creative, I was always making stuff. I was doing stuff for my mom, and just didn’t put the dots together.

When I was a little boy, I used to collect models of airplanes, and I’d put them on strings all in my bedroom. I’d look at the airplanes flying around. I didn’t know years later I was going to travel. I never connected. People would say, “Mark, you want to travel the world?” And I said, “No, no, I’m just making – I just like making airplanes”.

AR So what are you planning for your show Cerberus in London this October?

MB A series of paintings. There is a video [Dancing in the Street, 2019]. I’ve been working on these for about two years. Some of them are based on one of the paintings here and then it just goes where it goes.

AR Does it always go where it goes?

MB Unfortunately.

AR But that can be good: the worrying thing for a lot of people is that it goes nowhere.

MB You know, I grew up in a very unstructured environment; I grew up in a fluid environment. My mother was an orphan very young – at three. She was raised by family members. So she has a very organic, ‘go with the flow’ kind of thing, and when she had me, we went with the flow. I think that whatever you naturally have, you always look for a little bit of the other. So structure was something I was always trying for – well, I was kind of fake-looking for it.

AR You never have a moment when you get into the studio and nothing happens?

MB No. Jesus Christ, no. It goes, it always goes. I’m always trying to structure.

AR So you have a structure?

MB It’s like, “Holy shit: hold it!” The flow I can do, but the structuring, I really need to pump the brakes. That’s what I’m telling myself all the time, “Mark, pump the brakes, pump the brakes”.

AR Do you exhaust places? Do they stop intriguing you?

MB Sometimes what I get less and less intrigued by are just white boxes.

AR Interchangeable ones.

MB Yes, interchangeable white boxes sometimes. One thing I like about being here [in Shanghai] is you see history stretch out a little bit more than just the West, where all cultures started in the Greco-Roman, and that for me is super exciting. I think it’s healthy for a [Western] artist to get out of the West sometimes and see that they don’t need us. Just because you walk in, doesn’t mean that the room always turns to read you. That’s really exciting, because it opens up how you think about Asia, how you think about Africa. You think about all these different people and cultures that we’re taught are, at best, second-class citizens in our school.

Los Angeles is on show at the Long Museum (West Bund), Shanghai, through 13 October. Admission is free. Cerberus is on show at Hauser & Wirth, London, from 2 October to 21 December