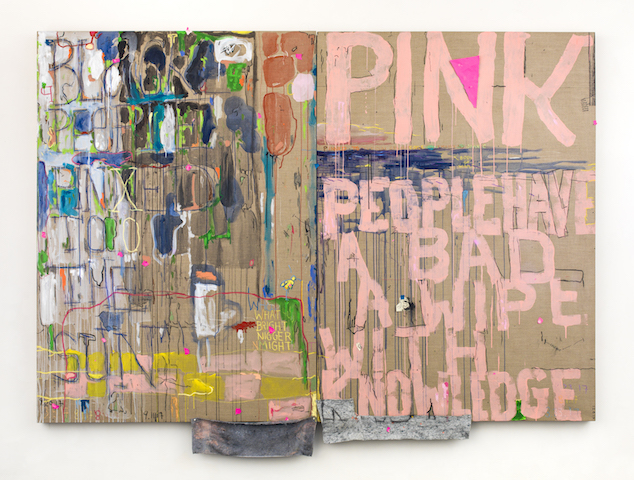

‘Black people are the window and the breaking of the window,’ reads Pope.L’s 2004 text drawing of the same title. ‘Purple people’, according to another work in his ‘Skin Set’ series (1997–2011), ‘are the end of orange people’, who elsewhere are defined as ‘god when She is shitting’. At Documenta 14 in Kassel, a selection of these works raised the dilemma (acute for the exhibition’s predominantly white European audience) of how to respond to the patent absurdity of such statements as White People Are the Cliffand What Comes After or Black People Are the Wet Grass at Morning (both 2001–02). The irresistible impulse to laugh is quickly overtaken by a commingled shame and anxiety. Isn’t it true, after a moment’s reflection, that historic injustices have been perpetrated in the name of racial definitions no less preposterous for having been supported by pseudosciences like phrenology or, let’s not forget, racist histories of art? And that equally imbecilic statements underpin the strain of identitarian politics that seems not only to persist in Europe and the United States but to be in the ascendant? And that people are dying as a consequence? So why was I laughing?

‘The friendliest black artist in America©’, as Pope.L’s business card puts it, clearly relishes the discomfiting effects of charged language. When in our email correspondence I ask him, with perhaps excessive decorum, whether member, the title of his forthcoming retrospective at the newly reopened MoMA, gestures at the same time to constituent parts of society and the body (it also derives from a 1996 walk through Harlem, the full title of which is Member a.k.a. Schlong Journey, for which he strapped a four-metre-long white pole to his crotch), he says that “it sounds funnier coming from you” before clarifying that his “original title of the exhibition was How Much Is That Nigger In The Window”. MoMA, perhaps unsurprisingly, “had concerns”. Factor in the unconventional nom de plume (a first name, William, has been dropped), and the impression is that words matter to this artist not because they are fixed but because they can be manipulated.

A mistrust of categorical distinctions also characterises a body of work – now showcased in a new installation for the Whitney and a collaborative performance supported by the Public Art Fund, as well as the MoMA exhibition, which focuses on a selection of key performances – that moves across painting, writing, theatre, video and sculpture. Yet the artist remains most closely associated with a series of public performances, including the early Times Square Crawl (1978) and Tompkins Square Crawl (1991), for which he dragged himself on his belly across crowded New York communal spaces. Reading as a protest against the city’s inequalities, a critique of the American dream and a reminder of the physical suffering that underpins progress as measured in a capitalist society, The Great White Way, 22 miles, 9 years, 1 street (2001–09) saw the artist don a Superman outfit, strap a skateboard to his back and, across a series of crawls spanning the first decade of the twenty-first century, heave himself along Broadway. For his latest piece of absurdist open-air theatre, titled Conquest and supported by the Public Art Fund, the artist and 140 volunteers will wriggle two-and-a-half kilometres across Manhattan.

These actions always had at their heart the social collective, Pope.L says, even if they were initially undertaken alone, because “I was the only one I could depend on to do it”. Yet their apparent expression of solidarity through self-abasement is provocative (a word one comes across a lot in researching these works), with early iterations drawing criticism from members of the public who read the performances as reinforcing racist stereotypes. The artist has previously stated, in an interview in bomb magazine, that ‘I crawl to remember’, and the action seems, like much of his work, to explore the space between felt experience (of suffering, of abjection) and the abstract definitions that shape people’s realities (for example, that one loosely identified group of people is superior to another). When pressed on what it was he was trying to call to mind on these crawls, he resists the implication that these social and collective memories can ever neatly be articulated: “I am trying to remember things I don’t want to forget and things – possibly things – things maybe I know but don’t know I know”.

Which calls to mind both Socrates’s equation of wisdom with awareness of one’s own ignorance and Donald Rumsfeld’s coining of the (unfairly maligned, in epistemological if not ethical terms) phrase ‘known unknowns’. This question of what it is even possible to articulate underpins works like Circa (2015), a series of 24 small paintings. Bearing the influence of language-based artists such as Joseph Kosuth, they combine the word ‘fuchsia’ with associated words drawn from a rap rhyme generator. That the paintings are rendered in a colour only vaguely resembling fuchsia, and that the word itself is consistently misspelled, firstly draws attention to the space between word and object and then posits it as a place – if you’ll forgive the lapse into the kind of ten-dollar language that the artist is apt to satirise – of free play outside the symbolic order. Which is to say a space outside the definitions through which people are kept ‘in their place’: “When people insist on a specific meaning,” he writes to me, “nine times out of ten, it’s a struggle for power… people use language to do things, to get things done, like say, enslave and control people”. The relationship between knowledge, language and power is explored in Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo (1972), in which American civilisation is threatened by a deadly epidemic of black culture closely resembling jazz. Attempts to restore order are led by an eight-hundred-year-old white European Crusader and leader of the Atonist cult (it’s complicated), who is accused by the novel’s protagonist of perpetuating the myth ‘that all Negroes experience the world the same way’ in order to prevent ‘them’ from breaking through ‘the ceiling above which no slave would be allowed to penetrate without stirring the kept bloodhounds’. The novel’s title plays on the corruption of the name of a West African god worshipped by early American slaves, which has come in English to denote meaningless or irrational speech. The categories enshrined in words – whether ‘Negroes’ or its more pejorative corruption – are the means by which minorities are not only ‘othered’ but subjugated. Meaning that it is a responsibility of writers and artists (and Pope.L is both) to disrupt the language of power.

One means of contesting the truth values contained in those words is to perform them, which is why we most closely associate the acting out of language with legal speech and its theatrical disputes over the meaning of laws written in black and white. Another (and one often taken by those denied equal access to the law) is, in the artist’s description, to “act out”, which he describes as “to misbehave, usually in a childish way”. This Dadaist refusal to conform to socially and linguistically determined expectations of the individual – by, for example, chaining oneself to a bank using a three-metre-long string of sausage while wearing only a skirt made out of dollar bills (ATM Piece, 1997) – “is always done to be witnessed. One acts out for and against an other.”

It is easy to find comparisons between Pope.L’s highly literary practice (he teaches writing and performance at the University of Chicago) and works such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), which also formalises the breakdown of order in the collapse of language by giving voice to a ghost. Which is to say, a repressed voice that breaks in unpredictable ways into the collective consciousness. This impulse to amplify invisible and unacknowledged voices haunts Pope.L’s Whispering Campaign (2017), which installed speakers in public spaces across Kassel and Athens so that residents would unexpectedly overhear snatches of stories in a variety of languages. The effect is to alert passersby to how many stories there are in the world that do not, because the speech of some is privileged over others, reach an audience.

These histories from below are also the subject of a new installation for the Whitney, which is, according to the advance information, ‘inspired by the fountain, the public arena, and John Cage’s conception of music and sound’. Like Whispering Campaign, the title of Choir both reflects the communal turn of these new works and suggests analogies between sound and society; where the former implies the spiteful and targeted dissemination of misinformation to destroy a reputation, the latter carries associations of harmony, collaboration and unity. But the artist warns that while the titles of the works “frame them as knowable… their construction does not”. So visitors shouldn’t expect any easy answers.

Nor should they expect solutions. ‘When you mix art + politics,’ reads a line in Rap Street Journal (1992), ‘you always end up treating the symptoms.’ Which, bearing in mind that this is the artist responsible for the 11m-long, pointedly tattered Stars and Stripes (Trinket, 2008/15) that flapped behind Kendrick Lamar as he performed at the Black Entertainment Television Awards in 2015, begs the question of whether or not art can ever address the underlying causes of the social injustice that his work protests. But, the artist responds, the question might be the wrong one: “Maybe after all there are only ever symptoms”.

If, as he goes on to suggest, “origins and causes are just distractions and fantasies”, then it’s as misguided to look for fundamental causes as it is to look for underlying truths of the kind that have historically been used to underpin power differentials. If the world is as we represent it, then the way we use language and images (which is to say art) is the means by which we create reality. But, once again, this thought only prompts a second take: are not such grandiose statements guilty of the same hubris – the belief that it is possible to grasp a whole truth, articulate a simple solution, apply abstract systems universally – that the artist has spent four decades undermining? “It’s kind of depressing isn’t it?” Pope.L writes at the end of our correspondence. “Uncertainty, contradiction, confusion! Ignorance is a virtue.”

Member: Pope.L 1978–2001 is on show at MoMA, New York, 21 October – January 2020; the performance Conquest took place in New York on 21 September; Choir is on show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, also in New York, 10 October – Winter 2020

All images courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

From the October 2019 issue of ArtReview