Editor’s note: ArtReview has invited some artists to consider the legacy of Nam June Paik’s today. Some of these answers were first published in the October 2019 issue, while others appear here for the first time.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (Young-hae Chang and Marc Voge)

How did you first encounter the work of Nam June Paik?

Paik accosted us in Paris, on the rue de Seine, in front of his hotel, La Louisiane, during the open market. Then he ran up to his room and brought us back a catalogue of his current show.

Do you have a favourite work?

Vidéo tricolore (1982) for its African-flavoured music soundtrack.

Has his work influenced your own work directly or indirectly?

Yes. It tells us that it’s perilous to work with a chaebol.

Do you see his work as having an influence more widely today?

Yes, as you can see.

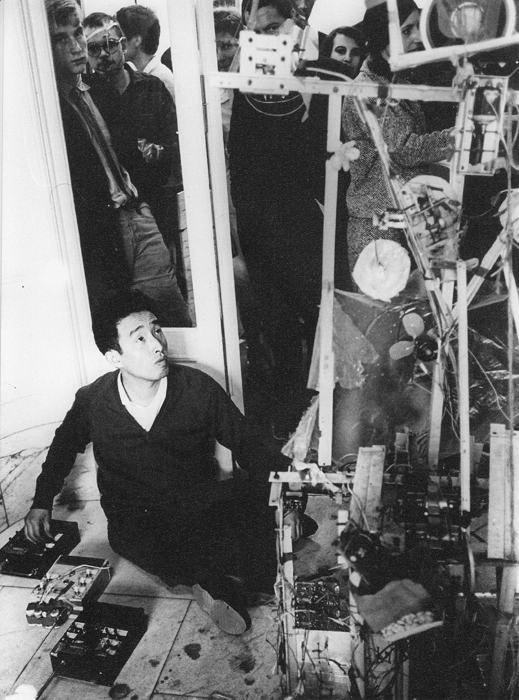

Aleksandra Domanović

The first works by Nam June Paik I came across were perhaps not the obvious ones. I was studying graphic design in Vienna but we had a course on video. Of course, this is Austria, so Fluxus dominated. Our teacher showed us this black-and-white documentation of a musical performance Paik did which was totally crazy, the band were on the floor; at one point he jumped off the stage, grabbed hold of John Cage, poured shampoo in his hair and cut off his tie. I recently saw the video synthesisers he made with Shuya Abe, at HKW in Berlin, in which there’s also this total sense of freedom, something I think we have lost in a lot of art today. My favourite work however is Magnet TV, from 1965, in which an industrial magnet is placed on top of a television set so as to interfere with the signal. It’s so direct as it unveils the meta-reality of technology; it hits you in the stomach like a bullet. To reveal how technology works, you need to break it.

Obviously technology has moved on since he was working, but I don’t think our relationship with it has really changed that much. Growing up when Yugoslavia, itself an unfinished utopia, was collapsing, I found it obvious that technology was neither intrinsically good or bad. My 2013 film .yu and .me is about the beginning of the internet in Yugoslavia. In the 1990s it promised to be a tool for freedom, but only because it was under the control of mathematicians and scientists; the more dominant technology of the time was television, however, and that was the enemy of the people, because it was entirely in the hands of Miloševic. As a consequence, it was impossible to get real information back then; television was a mechanism for filtering out the truth. Tech is like the sun: we need it, but it can cause an incredible amount of damage.

Haroon Mirza

I first saw Nam June Paik in his Guggenheim show in 2000 whilst on an art-school trip. It was a wonderfully installed show with many works, including collaborative pieces with Merce Cunningham. There were also lasers.

At the time I remember wondering how one of the artworks qualified as art, yet having an overwhelming feeling of reassurance that it was in a museum. It was a piece called Random Access (1963/2000), which consisted of seemingly randomly placed strips of magnetic tape adhered to the white gallery wall. There was also a tape head hanging next to it, and one could rub it against the tape to audibly reveal what was encoded on there. I think it is very clear my work is influenced by Paik.

I would say that he is one of the undisputed godfathers of media art: art that is made with mass-media technologies of the twentieth century. He’s also super interesting because he introduced an Eastern ideology to the West, and so as my recent collaborator Victor Wang would argue, it was a Korean that invented media art – not an American. I think living in New York with people like Marshall McLuhan around him really paved the way for a new genre in art to emerge.

Jae-Eun Choi

In 1986 I saw Nam June Paik’s performance with Joseph Beuys at Sogetsu Art Center in Tokyo. It was around the time I was starting my career as a young artist in Japan. Since then our paths coincided at two significant national art events of Korea. We were both invited to show at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, in commemoration of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, and then also at the Taejon Expo in 1993. We became close friends as artists working mainly outside of our motherland.

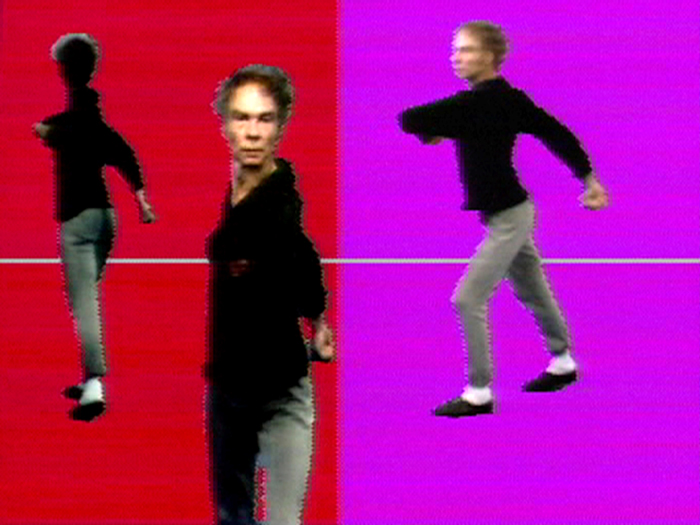

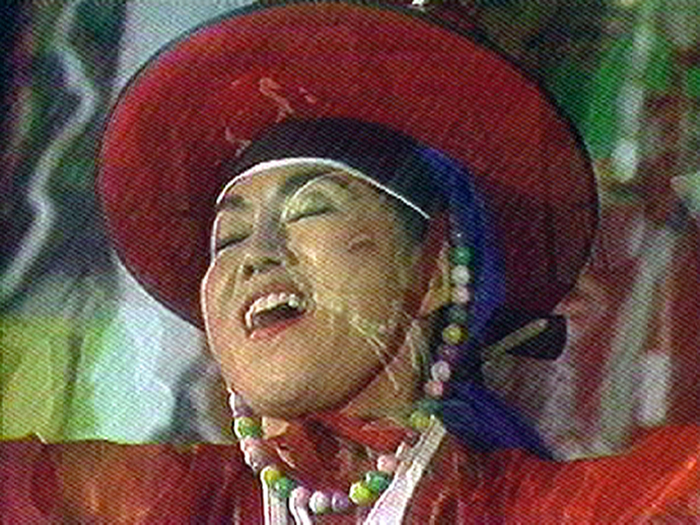

I particularly like his works Bye Bye Kipling (1986) and Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984). Witnessing the collaborative production process of Bye Bye Kipling in Japan was a shocking lesson for me, and his audacious will to connect the world through his art back then is still a powerful inspiration today.

Paik taught me to love Korean culture and be bold in scale. He believed that the peculiar shamanistic culture of Korea, what he referred to as ‘phantasm’, allowed Korean artists to fantasise and dream in largescale. I have been developing a collaborative project around the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone) in Korea for the past five years. Every time I run into a wall, I ask myself, “What would Nam June Paik have done?” Although he is not here with us today, he is my spiritual teacher for the DMZ project. Nam June Paik was a pioneer. He had already lived a world that we are only now learning to see.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

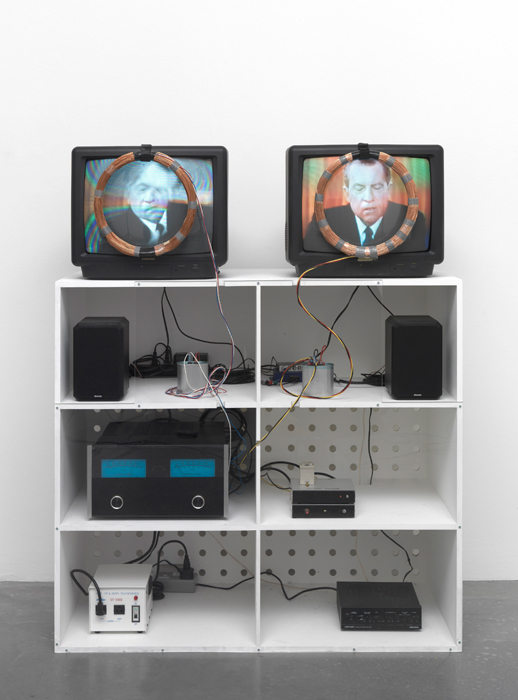

I do not remember the first time I encountered the work of Nam June Paik, but I think it involved a piano. Nixon (1965/2002) is one of the best examples of a work in which form and content are collapsed; conjoined so concisely and beautifully that the political claim and the technological intervention are inseparably intertwined. I think I took a lot from his work as a formalisation of what I took from Marshall McLuhan. That is a foundational encounter with the understanding that mediation itself is an aesthetic practice. His work made me attuned to the politics of amplification, network and broadcast. By now his influence has reached a level that is so pervasive to artists working with the politics of technology that it has become invisible.

A retrospective of Nam June Paik’s work is on view at Tate Modern through 9 February 2020

Further reading

Read Nam June Paik today – Part I, including responses by Koki Tanaka, Yuko Mohri, Samson Young and Ho Tzu Nyen

Juliet Jacques on Nam June Paik’s revolutionary work Good Morning, Mr Orwell

Published online on 18 October 2019