The installations, drawings, texts and videos in Julie Becker’s first retrospective – surveying a career cut short by the Los Angeles-based artist’s suicide in 2016 – are preoccupied by correspondence, in both senses: as communication between different parties and a means of identifying hidden patterns in, and thus codebreaking, the world.

Over three purpose-built interconnecting stage-sets on the ICA’s ground floor, the architectural installation Researchers, Residents, A Place To Rest (1993–96) riffs on Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), a narrative propelled by thwarted creativity, the return of the repressed and manifold failures to communicate. An antechamber is decked out as a bland office waiting-room: engraved desk nameplates (‘Entertainment Agency’, ‘Real Estate Agent’, ‘Psychiatrist’) suggest the different functions served by this makeshift building, while newspaper clippings show female switchboard operators making connections. A framed floorplan and copy of TV Guide illustrated with a scene from the film foreshadow a sprawling scale-model of the haunted Overlook Hotel that dominates the next room.

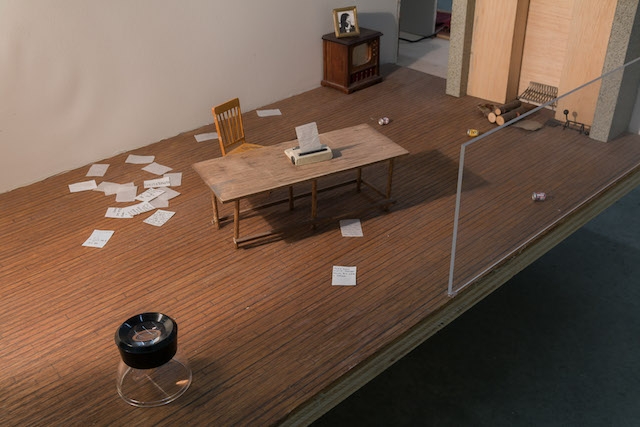

Several scenes in this intricately realised dollhouse are recognisable from the film – through Jack Torrance’s writing room are strewn tiny, crumpled cans of Coors and sheaves of paper from his novel-in-progress – while others seem to be speculations by the artist on the past or future life of the hotel – in a backroom resembling a hoard of objects from the hotel, a selection of guests are categorised by psychological type and given written backstories. That there are no people present other than via evidence of their having attempted to communicate with each other and the world outside – Lilliputian letters and diaries, typewriters and telephones, radio sets and a Ouija board – reinforces the impression of a crime scene littered with clues that, once the hidden links between them are revealed, will resolve the question of what, precisely, is going on.

Yet that desire to uncover esoteric connections – between people, events and things – is repeatedly frustrated. The video installation Transformation and Seduction (1993–2000) twins found cinematic footage of a girl running innocently through woodland with a voiceover adapting the opening of Vladimir Nabokov’s Despair (1934), in which the unreliable narrator encounters a doppelgänger in the woods that he then plots to kill. Yet, as no one else can see the resemblance between the narrator and his supposed double, it’s difficult in Becker’s splice to reconcile the narratives described by sinister words with innocent images without wilfully misinterpreting the latter as menacing, against their ostensible function. The work plays on the viewer’s preparedness to misread one dataset in order to reconcile it with another, and to pursue any tenuous link between the two that might justify that reconciliation. Given that the voiceover was, in the original version of the film, written and delivered by the artist’s father, for example, the title might allude to the biological processes of transformation and transduction by which genetic information is passed on. But it probably doesn’t.

These doublings, delusions and misrecognitions are one recurring theme – the shared frailties of physical and psychological architectures are another – of Becker’s drawings, which line the walls of the ICA’s upper galleries. The most startling is I Am Am I? (2003), in which a pencil drawing of a mirror frame is filled in with reflective foil, returning to the viewer a crumpled and uncanny self-image. It hangs beside a video installation that in isolation appears conceptually slight: Suburban Legend (1999) reproduces the teenage experience of watching The Wizard of Oz while listening to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon on headphones. A text in which the artist lists the supposed synchronicities preempts the viewer’s disillusion: when you’re not stoned, it’s clear that these ‘karmic correspondences’ are nothing more than coincidence.

The narrators of both The Shining and Despair are self-identifying artists who, harbouring delusions of grandeur, perceive in the surrounding world hidden messages that lead them to murder. The negative revelation of I Must Create a Masterpiece to Pay the Rent – that hidden connections rarely materialise, that paper trails don’t necessarily lead anywhere and that complex sets of relations do not conceal a simple unifying truth – feels, in the midst of an era shaped by conspiracy theories, paranoid delusion and quasi-mystical cults, like a valuable type of disenchantment.

Julie Becker: I Must Create a Masterpiece to Pay the Rent at ICA, London, 8 June – 12 August

From the September 2018 issue of ArtReview