At first glance Infinite Resignation seems to be a high-end toilet book, a collection of original and assembled philosophical-poetic fragments, short essays and aphorisms to be stored next to old copies of Viz and leafed through at random. However, it’s advisable to read the flowering of its ‘efflorescent grumpiness’ in sequence, as Thacker’s tussles with the ‘quasi-philosophy’ of pessimism accumulate detail. Pessimism – here a transient point or double-bind between suicidal despair and optimism, philosophy and mysticism, tragedy and farce – can, we learn, be moral, physical, metaphysical and even cosmic. ‘I am a pessimist about everything, except pessimism,’ Thacker writes, and shortly after: ‘There is no philosophy of pessimism, only the reverse.’

Nonetheless Infinite Resignation serves as an engaging introduction to Thacker’s patron saints of pessimistic thinking – ‘Laconic and sullen… perhaps they need us more than we need them’ – chiefly, Nicolas de Chamfort, Friedrich Nietzsche, Emil Cioran, Søren Kierkegaard, Blaise Pascal, Miguel de Unamuno and above all Arthur Schopenhauer. In some senses the entire book is both a dedication and ongoing response to Schopenhauer, who is both rendered in preposterous vignettes (a tragic courtship attempt involving a bunch of grapes; being pelted by school children with balls on his daily walks) and treated with seriousness. ‘If a thinker like Schopenhauer has any redeeming qualities, it is that he identified the great lie of Western culture – the preference for existence over non-existence.’ As Thacker notes, quoting Schopenhauer: ‘at the end of his life, no one, if he be sincere and at the same time in possession of his faculties, will ever wish to go through it again’. Under Schopenhauer’s shadow, Thacker’s pessimistic fragments self-reflexively worm through the pointlessness of philosophy proper, of life as a disenchanted writer and of writing itself. Somewhat unusually given its frequent references to pathology, there is also an invigorating lack of reference to psychoanalysis.

Existence/nonexistence for Thacker is also entwined with the probing of the human in relation to the nonhuman that has preoccupied his work to date (including the New York-based academic’s cult 2011 In the Dust of This Planet). Stemming from weirder brands of dark ecology, the book branches into the tantalising prospect of eradicating the pestilence of humanity in favour of a-world-without-us and/or general self- abnegation. This is one of many similarities between Thacker’s pessimism and the (disturbingly purist) aspects of mysticism – but as it cannot fully commit to either absence or mysticism, it wallows around them without resolution. This noncommittal attitude is perhaps Infinite Resignation’s greatest strength, though: it exemplifies in its form and content what could be called a pessimistic style. Aphoristic fragments are not short for wisdom’s sake, rather they are short because of ‘laziness, listlessness’, Thacker admits. ‘The pessimist harbors no ideals concerning literary craft of “ finding one’s voice” as a writer. There is only what suffices, what is finished enough, what can be left off, cast away, abandoned when it physically hurts too much to write so much and to sit for so long.’ Paying homage to Nietzsche’s ‘style as illness’ and Schopenhauer’s ‘style as intolerance’, Thacker’s championing of everyday tedium as an aesthetic is a refreshing addition to the contemporary resurgence of interest in the possibilities of the hybrid essay form. The book also repeats itself at points and perhaps goes on too long – but shouldn’t it?

One notable absence in Infinite Resignation is references to women writers. This is the domain of the dispirited male academic who pities and laughs at himself in turns. The exception is a short paragraph on Clarice Lispector’s surreal visions of plankton and insects. And yet, Lispector’s influence seeps through the book almost as much as Schopenhauer’s via Thacker’s interspersed short poetic sentences on strange undersea worlds of stars and plants, often the only counterpoints to the seething disappointment of pessimism: ‘Written in the Hall of Mosses. Thought wanders in eerie shapes, growing in unexpected, verdant directions. Slowly, imperceptibly, it covers the entire surface of the brain. It drapes itself like a viscous and dazzling early morning moss.’ But, horror, the loo roll has run out again.

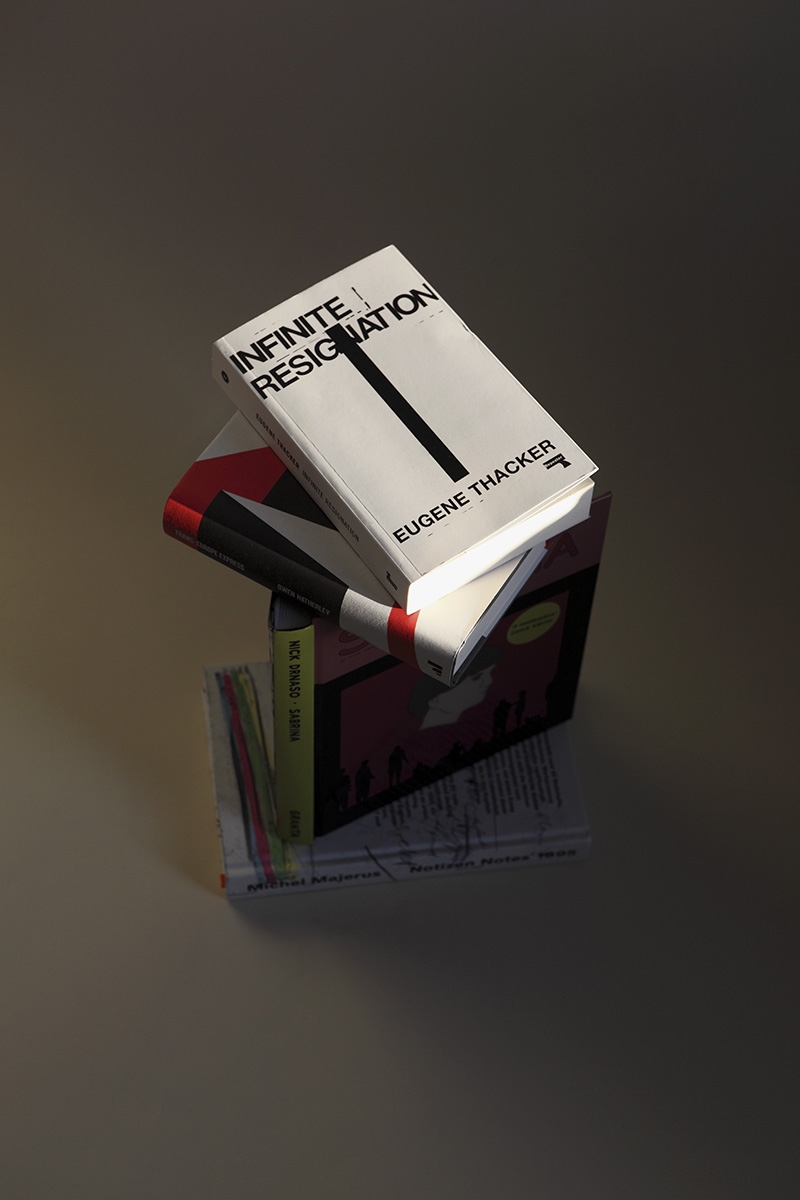

Infinite Resignation by Eugene Thacker, Repeater, £12.99/$17.95 (softcover)

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview