Paola Pivi, Perrotin Tokyo, through 11 November

They all look the same. The seasonal-preview-writer’s rulebook states, categorically, that this last sentence is no way to begin a summary of exhibitions that you’re inviting readers to check out over the coming months. If there’s an equivalent manual for gallerists, then presumably the same phrase has similar prohibitions relating to its use as a title for a commercial art exhibition. The thing about selling the contemporary is that you are required to feed your customers a steady diet of difference, uniqueness even; people never want ‘the same’. Nevertheless, They all look the same is the title of Italian Paola Pivi’s latest exhibition at Perrotin in Tokyo. She’s a bit of a joker: her last exhibition at Perrotin New York was titled OK, you are better than me, so what? She presented a collection of her signature lifesize feathered polar bears in that show; she’s showing more polar bears here. They’re formed naturalistically out of urethane foam and covered, unnaturalistically, in feathers rather than fur. That last gives them the appearance of a child’s toy that’s been washed once too often (think Sebastian Flyte). And, weirdly, that makes them feel more familiar than an actual polar bear. The artist herself, who lives in Alaska, considers the actual animals her ‘neighbours’. Often her bears look suitably depressed about that. After all, they’re unnaturally naturalised. They come in a variety of more-or-less garish colours and are frozen in a variety of poses that suggest dancing, sitting, slumping and sprawling. Overall they seem to contain equal measures of the surreal, the cartoonish and the sublime. The bears in the Tokyo show will be complemented by a series of kinetic sculptures featuring bicycle wheels adorned with various bird feathers. The latter, we are told, are sourced in Japan (where, as it happens, Pivi’s work is also included in the ongoing Yokohama Triennale). Does that make them site specific? Multicultural?

Jesper Just, Perrotin Hong Kong, through 11 November

Maybe multinational. Which leads us seamlessly over to Perrotin’s Hong Kong space, where there’s something different: Jesper Just’s Continuous Monuments (Interpassivities). The title references influential late-1960s radical architects Superstudio’s (semiironic) proposal for a continuous, monotonous, grid-based, urban form that would pass over or around fields, mountains, rivers and existing cities, and builds on the Danish artist’s interest in architecture and the effects of the built environment on social formation, which came to the fore during Intercourses, Just’s multichannel video installation for the Danish Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale. The Hong Kong show also nods to Interpassivities, Just’s recent collaborative performance with the Royal Danish Ballet (with music by Kim Gordon), which took place this past March in Copenhagen. Featuring a mix of recorded and live material, it was based on a Jorge Luis Borges story ‘On Exactitude in Science’ (1946), itself based on a scene from Lewis Carroll’s final novel, Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1889), concerning an obsession with cartographic accuracy that escalates until the map is the same size as the territory. Asked if the map in question has ever been laid out, one of Carroll’s characters replies: ‘The farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.’ Expect some musing on the fluid interrelationships between reality and its representation then, and the ways in which environments shape the territory of things such as labour, relationships and gender.

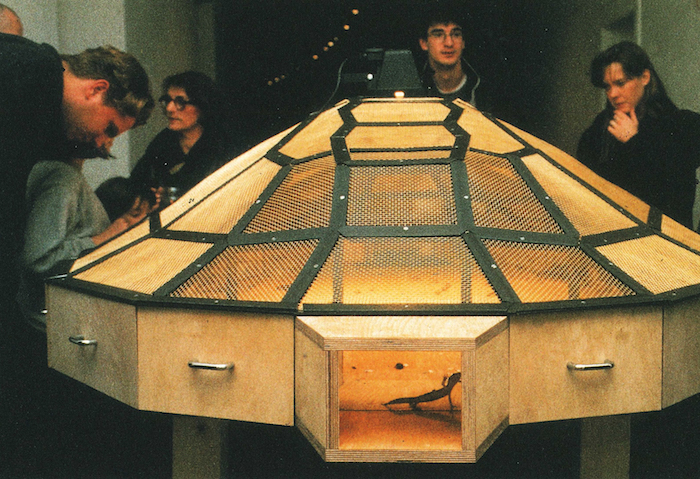

Art and China After 1989: Theatre of the World, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 6 October – 7 January

Mapping a territory is certainly the theme of the Guggenheim’s big autumn show, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World. You’ll have observed a certain grandiosity (and remapping) in that schema – China as the centre of the world via a show in New York – which might have made Carroll’s mapmakers proud, but which also hints at the fact that this is a hugely ambitious project. Curated by the Guggenheim’s Alexandra Munroe with assistance from MAXXI’s Hou Hanru and UCCA’s Philip Tinari, the exhibition maps out a temporal span starting at the end of the Cold War and ending with the rise of globalism (taking in two generations of conceptualist artists). In spatial terms it’s about China and – more ambitiously still – art’s role in anticipating ‘the sweeping social transformation that has bought China to the center of global attention’. In real terms it features work by 75 artists and collectives, ranging from Ai Weiwei (of course) to Zhou Tiehai (whose landmark nine-act film Will/We Must (1997), cruelly skewering the ambitions and realities of China’s contemporary art scene at the time, together with a series of associated paintings, was recently on show at Shanghai’s Yuz Museum). Look out also for Huang Yong Ping’s Theatre of the World (1993), a cagelike structure in which thousands of live scorpions, beetles and ‘lesser’ insects will gradually devour each other over the course of the show. Who needs Mayweather vs. McGregor? This shit is real. Or at least as real as it gets in an art gallery.

Hyper Real, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 20 October – 18 February

That said, things are even more real over in Canberra, at the National Gallery of Australia’s Hyper Real exhibition, where the word ‘uncanny’ will doubtless be bounced around more times than a squash ball. More real than real is a ‘thing’ in Australian sculpture, so expect to be freaked out by works by Patricia Piccinini, Ron Mueck and Sam Jinks. The exhibition maps out sculpture produced between 1973 and the present day, and also samples from the oeuvres of Maurizio Cattelan and earlier pioneers, such as the late, great Duane Hanson, of the sculptural real. Pick of the bunch, however, might be Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Old Person’s Home (2007), in which 13 lifesize sculptures of world leaders (of a generation ago: think Yasser Arafat), aged and decrepit, engage in a version of automated dodgem in their motorised wheelchairs. The faces may change, but the game does not…

Zhongguo 2185, Sadie Coles HQ, London, 21 September – 5 November

Except the Chinese art game of course, which remains the flavour of the next few months, this time in London, where Sadie Coles HQ will stage Zhongguo 2185, a group exhibition of work by young Chinese artists, just in time for the Frieze London art fair. The exhibition’s title derives from the first (unpublished) novel by Chinese sci-fi star Cixin Liu. Best-known internationally for his Three-Body Problem trilogy (2007–10), Liu wrote Zhongguo 2185 (China 2185) in the spring of 1989, and the text has since circulated (in Chinese only) on the Internet. The work itself concerns a young computer engineer’s visit to the Mao Mausoleum in Tiananmen Square (the story was written just before the protests), which leads to the virtual resurrection of the Chairman’s consciousness (along with those of five other dead individuals), which in turn leads to the creation of an online utopian revolution and republic, which begins to affect ‘realworld’ China. The republic and the revolution eventually die out, leaving behind a debate about that most fashionable of art subjects: posthuman alterity. Curator Victor Wang will be planting works by Yu Ji, Lu Yang, Nabuqi, Zhang Ruyi (see the spring 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia for more on her), Sun Xun and Tianzhuo Chen in that fertile soil.

Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum, through 12 November

And fertile it certainly is, for back in China, Frenchman Céleste Boursier-Mougenot will be offering his own vision of posthumanism at Shanghai’s Minsheng Museum. SONSARA (in the spirit of cultural exchange, the exhibition title fuses the French word for sound – son – with the Sanskrit Saṃsāra – an idea developed in the Vedic Upanishads that denotes the world, in the sense of the cyclical nature of existence) will feature six sound installations. The exhibition seeks to tackle the twin issues of ‘how humans co-exist with the artificial nature’ and ‘building an ecology, imaging the world after human’. What does that actually mean? The artist’s installation clinamen (2013), for example, features a collection of variously sized white porcelain bowls, floating in an intensely blue-lined tank of water and producing bell-like sounds as they randomly clank into each other.

Occulture: The Dark Arts, City Gallery Wellington, through 19 November

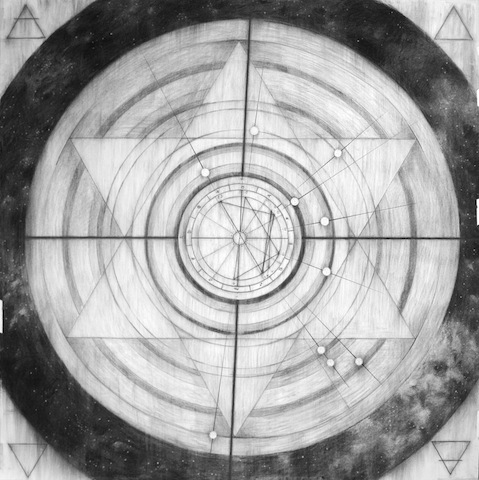

‘All art is Magick,’ wrote the turn-of-the-century English occultist and sometime painter Aleister Crowley (no stranger to Vedic philosophy himself). Crowley took up the brush during the First World War while in the US, campaigning for the German war effort – a move he later claimed was an infiltration at the behest of the British secret services: Magick. Still, the earlier quotation is the jumping-off point for the City Gallery Wellington’s group exhibition Occulture: The Dark Arts, which aims at exploring the ways in which art has drawn on the occult and the esoteric in order to explore alterity. On show, among other things, will be Kenneth Anger’s short film Lucifer Rising (1972 – incidentally, but because everything is connected – Anger met Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page when the pair were bidding for a piece of Crowley memorabilia in London and convinced him to compose a soundtrack to the film; Anger later fell out with Page, ending the project, and Page’s music for the film was released only in 2012) and a wallpainting by Australian Mikala Dwyer. The highlight, however, may well be Taiwan-based Yin-Ju Chen’s mandalalike Liquidation Maps (2014), a series of five charcoal charts that investigate five political genocides and massacres in recent Asian history (the 1987 Lieyu Kinmen Massacre in Taipei; the 1942 Sook Ching Massacres in Singapore; the 1975–9 Cambodian genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge; the 1999 East Timor massacres; and the 1980 Gwangju Uprising in South Korea) through the lens of astrology and astronomy in order to engage with themes of predetermination, cosmic planning and subjective views of history. The Liquidation Maps also feature in the group show Interrupted Survey: Fractured Modern Mythologies at the ACC in Gwangju (through 30 Sept).

Colonial Sugar, City Gallery Wellington, through 19 November

When it comes to the reconsideration of atrocities, the City Gallery is on something of a roll. Concurrently with Occulture, the institution is staging Colonial Sugar, a two-person exhibition that investigates the legacy of the British colonial sugar trade and, more particularly, that of the 62,000 people who, between 1863 and 1904, were taken from their homes in the Pacific and enslaved on sugarcane plantations in Queensland Australia. The practice ended when sugar was declared a ‘white industry’ and many of the slaves were deported. Jasmine Togo-Brisby, an Australian South Sea Islander whose great-great-grandparents were taken from Vanuatu as children, shows Bitter Sweet (2015), a pile of skulls cast in unrefined sugar and resin (and prompted by the discovery of an unmarked mass grave in Queensland), while Sydney-based Tracey Moffatt (who is also representing Australia at this year’s Venice Biennale) shows Plantation (2009), a series of photographic diptychs, arranged in 12 chapters, that chronicle colonial ‘sugar slave’ tropes.

Sahej Rahal, CCA Glasgow, 16 September – 29 October

Mapping and the occult come together again in Mumbai-based performance and mixed-media artist Sahej Rahal’s Barricadia at the CCA Glasgow. Rahal’s work is notable for its fusing of history, mythology and popular culture in order to create metanarratives that interrogate the realities of contemporary urban life. The exhibition features a series of new works created during a residency at Cove Park, overlooking Loch Long on Scotland’s West Coast. These include a series of drawings, a development of Rahal’s recent videowork The Dry Salvages (2017, named after the third of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, 1943, in which the British writer continues his meditation on mankind’s relation to time through a mix of Eastern and Western theology – in this case the image of Krishna) and a series of works, centred around an imagined grimoire and various other artefacts relating to the borders and land of ‘Barricadia’. The exhibition as a whole merges fact and fiction to comment on current political events in India: notably a series of Islamophobic lynchings and the subsequent public response. This is the second in a series of three episodic exhibitions, the final instalment of which will be on show at the MAC, Birmingham in 2018.

From the Autumn 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia