Much can been read into the politics of Ai Weiwei’s name in China over the last few years, the rate at which it is omitted from exhibitions, catalogues and the public sphere in general corresponding inversely to the level of hearsay and idle chatter about him.

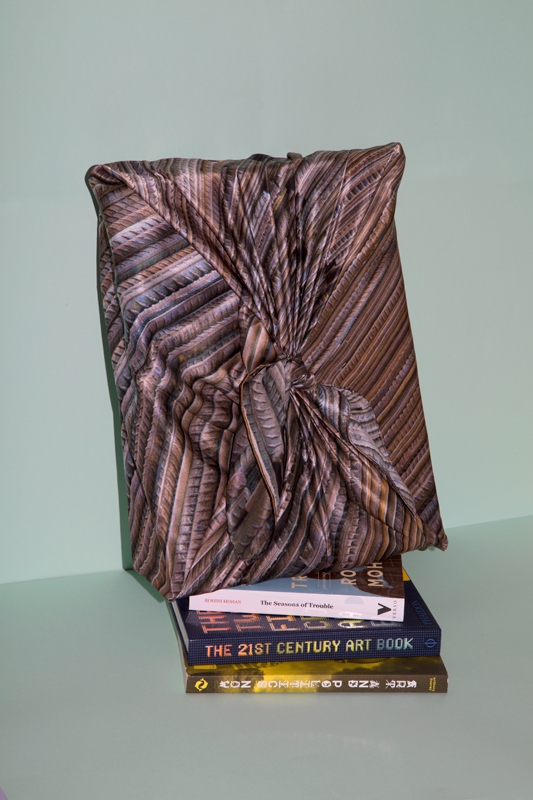

Taschen’s eponymous book offers two editions: the hardcover edition is a 724-page coffee table (33 by 44 cm) clothbound book wrapped in a Habotai silk scarf (the design is based on a detail from Ai’s work Straight, a reference to the Sichuan earthquake of 2008); the art edition – sold out by the time of writing – adds an 18.2 by 76.3 by 52.2 cm marble lectern. The book features a chronological account of the artist’s career from 1983 to the present, juxtaposing artworks with Ai’s running commentary on their context and production, and on his authorial intentions. In addition, it features articles by curator Roger M. Buergel, international relations professor William A. Callahan, oriental art dealer James J. Lally, Chinese cultural studies professor Carlos Rojas and collector Uli Sigg. While each contributes a different perspective to the discussion, collectively they offer little beyond established commentaries, and either overtly or covertly support the book’s apparent aim of perpetuating the now iconic image of Ai as the singular personality shining out amidst the menacing and faceless background of China’s ruling regime and its docile subjects.

It should be evident that Ai is no longer interested in making art. It can be argued that Ai, by abolishing the border between art and activism, simply mirrors the mechanisms of control that collapse discourse into proclamation, rather than reflecting on what has made them possible. His constant provocation that demands social injustice to show itself as such creates the opposite effect of concealment and trivialisation; the countering face of power summoned forth by Ai’s work is brutal and unrelenting, but it is also tailored neatly to construct the required interpretation of the authoritarian condition. By becoming a recording machine of duelling forces, Ai retrogrades into a redundant object of an experiment whose results have long been translated into axioms of good and evil, thus cornering his methodology into a process of self-victimisation that threatens to collapse unless simultaneously transformed into a global spectacle.

This logic of confrontation has recently reached its ideal form: the absence or removal of the name now becomes a sign of something substantial or authentic, constituting a narrative of the underground that has, from the beginning, fuelled the marketisation of Chinese contemporary art, serving Western collectors’ expectation for a Chinese art that critiques authoritarian control from the shadows. The politics of the name ultimately degenerates into an economy of the signature. Thus in response to Sigg’s determination of Ai’s identity as an ‘activist-artist’, Rojas’s comment on his strategy as ‘making visible the state’s politics of visibility’ and Buergel’s assertion of his political status as homo sacer, the most problematic aspect of Ai’s work is not that it is bad, but the extent to which it relies on an intellectual framework that allows even incompetent forms of activism, including daily tweets constantly reminding the world of his disenfranchisement, to be sanctioned or even celebrated in the name of art. Undermining both the art of activism and activist potential of art at the same time, the purported direct social critique that characterises his production falls prey to one of the most ancient criticisms of art: that it’s a form of imitation without insight.

This article was first published in the Spring 2015 issue of ArtReview Asia.