Early in the feature film Women Without Men (2009), set in Tehran during the 1953 coup d’état, a young woman visits a friend who is housebound but desperate to participate in the political actions out on the streets. “But why? It’s just a lot of idiots making trouble outside!” chides the woman. In the work of the film’s director, Shirin Neshat, the courage to engage in political action is closely linked to an understanding of the creative act as a counterpoint to oppression: the melancholy legato of the singer soaring against the snap of jackboots on flagstone; poetry in the law courts; the will to become visible and audible when comfort and security rest in remaining silent and unseen. “I don’t want to make ‘political art’,” explains Neshat, who returns to these themes over and over again in both her artwork and her feature-film projects, “but I can’t help it.” In part this is involuntary: her work investigates areas – religion, gender, the recent history of the Middle East – in which any form of expression will be identified as political, for better or worse, whether she desires it or not. In part it is because for Neshat the ‘political’ is not something abstract and apart, but something intertwined with every aspect of life; you may set out looking for family, for cultural identity, for love, but eventually you will always find politics.

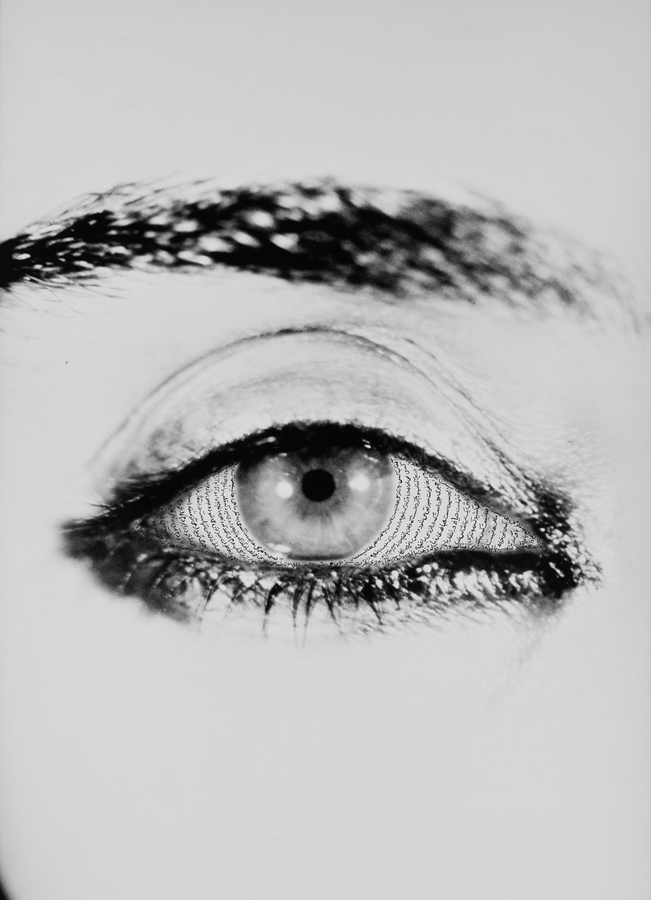

Neshat does not create lightly, or fast, and is “not drawn to the celebrity world of art fairs”. During the ten years after completing her MFA at UC Berkeley, she produced almost no artwork, only recommencing in 1993, following her first trip back to Iran, a country she had left some 19 years previously as a seventeen-yearold student, and to which – following the Islamic Revolution of 1979 – she had until then been unable to return. She came to wider attention with the subsequent Women of Allah (1993–7) – a series of photographs of Iranian women inscribed with calligraphic Farsi text that now forms the first part in an informal trilogy currently on show at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha. In common with Women of Allah, The Book of Kings (2012) and Our House Is on Fire (2013) portray the hidden faces of revolution – not the heroes of the frontline, but those who endure its aftermath.

Nida (Patriots), from The Book of Kings series, 2012. © the artist. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York & Brussels

Ferdowsi’s epic poem Shahnameh (The Book of Kings, c. 977–1010 AD) combines myth and history in telling the story of Persia. In its themes of patriotism, violence, sacrifice and conquest, Neshat found echoes of her own interest in the struggles of the present day; her Book of Kings was started after the suppression of Iran’s Green Movement in 2010 – a pro-democracy uprising that she had supported from her hometown of New York. Cast using other Iranian activists she had encountered in the American city, the 58 portraits of The Book of Kings divide a population – the actors in a history – into Masses, Patriots and Villains. Stripped to the waist and painted with the bloodied battle scenes that illustrate Ferdowsi’s poem, the Villains literally embody their own violence; portrayed in a uniform stance with hand on heart and the fixed, wide-eyed expression of the true believer, the Patriots are likewise defined by their role and beliefs, the text of the poem painted across their forms in regimented verse; it is instead in the irresolute and heterogeneous Masses – presented in a crowded grid of intense headshots, many depicting apparently traumatised subjects – that Neshat shows the less easily defined face of history’s witnesses.

In Our House Is on Fire, a work commissioned by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Neshat portrays the postrevolutionary condition of Cairo through its margins – those stooped and withered by illness, poverty, loss and the weight of years who stood around the edges of Tahrir Square as the young pushed to the forefront. Over two weeks, Neshat and longtime collaborator Larry Barns tracked down appropriate subjects from the neighbourhood surrounding Cairo’s Townhouse Gallery, bringing them into the gallery’s studio to share stories and to mourn the dead (Barns’s daughter Teal had also recently died). The tears seen in the subsequent portraits are real, though the barely visible veil of calligraphy that sits like dust on the images is revolutionary poetry, rather than the sitters’ stories; Neshat “never wrote down what they said, I just listened to them”. When shown as a series, the pictures of the living are hung alongside similarly sized portraits of the feet of the ‘dead’ as illustrations of absence.

Neshat’s approach to photography is more cinematic since she became a feature filmmaker

Unlike Women of Allah, these recent projects are comparatively hermetic – they have a tight internal structure more suggestive of narrative. Carefully cast, and with a strong narrative tension between the individual images, Neshat’s approach to photography is more cinematic since she became a feature filmmaker. Such interdependent image suites are alas ill-adapted to this era of image anarchy – in which individual pictures habitually float free first of their series companions, then of their artistic context, and even authorship – particularly since an overwhelming proportion of Neshat’s geographically farflung audience sees her work online via migrating gallery images and YouTube clips. The Mathaf show is her first solo exhibition in the Middle East, but the number of young women who came to hear her speak at an event for students the morning after the opening in Doha, and the size of the audience and the heated debate about her representation of women and the Middle East accompanying her recent screening and talks at the American University of Beirut give a sense of a public already engaged with her work via the Internet.

The popular reach of Women Without Men, which was screened more widely than Neshat has ever exhibited, combined with the fact that, unlike a migrating suite of photographs, even online it has an emphatic totality, has firmed up Neshat’s resolve to continue working in feature films. “To be honest, you reach a much bigger audience with cinema. I work within the reality of the artworld, and I feel there’s a limit to how far you can push the boundary of political art – but with the film world I feel there is the space for me.” Largely funded by governmental and private European foundations as well as Middle Eastern institutes that support films, Neshat’s movie projects are consciously geared towards a more general audience: more narrative, less enigmatic than her artwork, though sharing its aesthetic and intellectual sensibility.

The slow pace of Neshat’s working process evidences the constant self-questioning and the weight of responsibility she feels towards both her subjects and her audience (and the point of overlap between those): currently she is working on a new series of Azeri portraits for the opening exhibition of the Yarat Contemporary Art Space, in Baku (a not-for-profit founded by Aida Mahmudova, an artist and niece of Azerbaijan’s president), and is concerned to ensure that “people without any art education can enter the room and feel moved”. While the artworks remain the same whether she is showing in Doha or New York, and she is as committed to keep treading new ground, formally, conceptually and thematically, as she is to connect with fresh audiences, context has an unquestionable impact on the reading of her work; she feels simultaneously of New York’s artworld and alien to it, both of the Middle East and an outsider to it. Presenting Our House Is on Fire earlier this year at the Rauschenberg Foundation, she worried about how sad the work was, that it might be too “Eastern and emotional” for New York, that it was the kind of work that would never be purchased for a collection.

Souad, from Our House Is on Fire series, 2013. Photo: Larry Barns. © the artist. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York & Brussels

Neshat’s depth of consideration will be materially evidenced in Facing History, a show at the Hirshhorn Gallery in Washington, DC, later this year, that will include her notes and research materials – from newspaper clippings to interview notes to her original copy of the ancient Book of Kings – as well as historical footage, alongside the finished works: a provision of geopolitical and cultural-historical context unnecessary at Mathaf, but one that brings with it perhaps troublesome hints of historicity. Neshat is no documentarian; like Ferdowsi she celebrates the dimension that fiction has to add to history: “To me, imagination is emotion: I need to make art that is faithful to that rawness.”

This autumn, Neshat hopes to start shooting a long-planned feature film inspired by the Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum, whose soulful voice bewitched the Arabic-speaking world for some five decades during the middle of the last century. The figure of the singer is a familiar one in her work – in both Women Without Men and the double-screen videowork Turbulent (1998), song springs forth like an unmediated expression of the soul. Yet in researching Kulthum, the power of whose voice was such that she apparently raised audiences to states of near-sexual arousal, Neshat found evidence of an inner life to be fugitive: the more she researched, the more Kulthum seemed to fragment. Stretched thin between the responsibilities she feels towards her subject, her audience and her own creativity, Neshat has, after six years’ work on the project, opted for an idiosyncratic, somewhat surreal movie rather than a straight biopic. “No fiction film has ever been made about her [Kulthum] – how dare I make a film in a lighthearted way?” she says passionately. “There are people waiting for this film – I have to take responsibility. And I think in the end making a film that is personal saves my ass from people saying ‘that’s not true’ or ‘this is not authentic’.”

Describing her as a public figure without a private world of love, who had essentially desexualised herself so that she could work in the world of men, it seems that at this point in the project, what Kulthum represents for Neshat is not the glory of the creative spirit but a cautionary tale about the loss of emotion, and with it, the loss of imagination.

Watch the artist’s Regents’ Lecture ‘From Photography to Cinema’ delivered at UC Berkeley in 2013.

This article was first published in the Spring 2015 issue of ArtReview Asia.