The opening scene of Wang Bing’s directorial debut, the nine-hour documentary Tie Xi Qu (West of the Tracks, 2003), is shot from a slow-moving train through the snowflake-covered lens of a digital video camera. Accompanied by the low roar of wheels on frozen, rusted rails, the camera navigates a landscape of dilapidated factory buildings in a once-booming, now rapidly declining industrial zone in northeast China. This point of departure for Wang’s career echoes the overlapping histories of early cinema and industrial modernity, intimately tied to trains and the particular forms of visual experience that moving images produce. While early cinema often celebrated the magic of the cinematic apparatus and the modern technologies of industrialisation, Wang’s films casts a melancholy gaze on industry’s decay. Over the course of his career, he has documented vanishing worlds and lived spaces in their most unadorned forms; yet his investigative and immersive approach has remained unsentimental and understated in its implicit critique of China’s social realities.

Born in 1967, Wang Bing grew up during the Cultural Revolution and later witnessed how his country’s reform-era experiments with capitalist production took a toll on citizens who struggled to adapt to the change. The arc of his career, which began during the late 1990s, was closely aligned with the rise of digital video as an accessible and mobile technology, one that enabled him to document the social worlds of marginalised individuals in ways previously unseen in mainstream cinema and broadcast journalism in China. Wang has long been recognised as a significant director by the international cinema community and is no stranger to the festival circuit, while a recent retrospective of his films as part of Documenta 14 illustrated his embrace by the contemporary art world. Yet his films have rarely been publicly screened in his home country, where for the better part of two decades he has worked to document those who labour precariously against the backdrop of dramatic social transformation.

Across his many films, his signature observational style has not merely been a passive mode of quiet nonintervention, but an active witness to the histories of those rocked by China’s tumultuous waves of change

A 2017 exhibition at Magician Space in Beijing, Experience and Poverty, marked Wang’s first solo show in China. Transposing his cinematic works into the space of the gallery, the opening coincided with the Beijing government’s campaign to forcibly remove millions of the so-called ‘low-end population’ from the city. The resonance was eerie: in a 2017 interview in The Brooklyn Rail, Wang stated that ‘cinema is not about composition or colour, but about balancing power dynamics, about continuous change’. For the exhibition, one of Magician Space’s white cubes was converted into a black box with rows of theatre seating, inviting the audience into a direct engagement with the durational contours of his practice. A scheduled programme of daily screenings functioned – at least as a gesture – to disrupt the tendency for wandering members of the fast-paced artworld to drift in and out of video installations without viewing the works in their entirety. Across his many films, his signature observational style has not merely been a passive mode of quiet nonintervention, but an active witness to the histories of those rocked by China’s tumultuous waves of change.

The exhibition featured Yizhi (Traces, 2014), Wang’s first work on celluloid. Using a small stockpile of black-and-white 35mm film – reportedly from the artist Yang Fudong – Wang’s roving, handheld camera surveys the unforgiving desert landscape of the Jiabiangou Labour Camp, where thousands of alleged reactionaries and rightists were sent, and later died, during the Mao era. What remains are fragments of bones, liquor bottles and hand-carved Chinese characters on the walls of caves counting down the days and scrawling out gasps for freedom. The film is projected from the ceiling onto the floor, and Wang’s physical presence at the site – the same place that inspired his narrative feature Jiabiangou (The Ditch, 2010) – is apparent in the trembling of the camera in his hands and the sound of heavy breathing. This is a stylistic echo of earlier works such as San Zimei (Three Sisters, 2012) and Feng Ai (’Til Madness Do Us Part, 2013), in which an embodied camera also travels through the disorderly terrain of everyday life, framing worlds with an unwavering desire to record and understand the lives of those excluded from power.

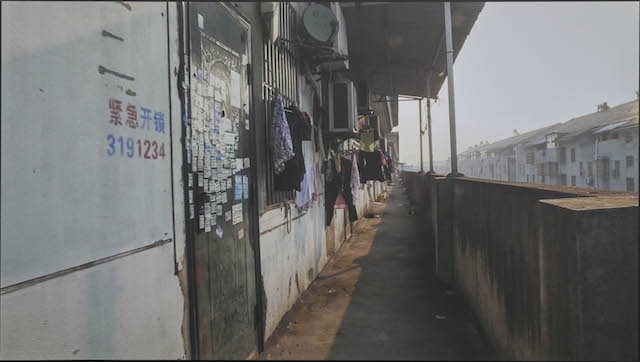

Fang Xiuying (Mrs Fang, 2017), which was awarded the Golden Leopard at the 2017 Locarno Film Festival, documents the final week of the protagonist’s life with an intimacy that borders on voyeurism. Her days are confined to bed in a bewildered, speechless silence as Alzheimer’s lays claim to her body and mind. The contrast between the family members who crowd busily around their matriarch and her powerless paralysis creates a tense, harsh portrait of a domestic space. Beyond the bare walls of the bedroom, we see vignettes from a local world where the pastimes include electrofishing and long rides on dirt roads through endless fields. This patience and attention to detail is equally apparent in 15 Hours (2017), which witnesses the daily rhythms of work in a textile factory in Zhejiang Province. This gruelling work recalls Wang’s West of the Tracks in making its main protagonist the factory itself, however many individuals we see working in it. The single-shot, 15-hour video accumulates raw poetic fragments: a glimpse of the English word ‘MADNESS’ on a worker’s T-shirt; the simultaneously deft and mechanical handiwork that pieces together hundreds of pairs of jeans in a single day; the way that light changes over several hours in spaces so vast that their limits vanish. The work extends Wang’s preoccupation with the labourers who make possible the nation’s economic boom, and who might be left behind by it.

Wang’s physical presence at the site is apparent in the trembling of the camera in his hands and the sound of heavy breathing

In recent years, documentary practices have gained prominence across the expansive field of contemporary art, though Wang’s films have rarely aligned with the trends of the moment. While the audience for Wang’s work has extended beyond film festivals, his recent validation by the contemporary art establishment points to a broader shift in the role that everyday happenings and their representations play in the artworld. As Hal Foster writes, ‘Despite rumors of its disappearance, the real remains with us.’ Excavating the real has always been central to Wang’s films, and his formal style has, in large part, remained unchanged throughout his career, to the extent that his cinematic approach flirts with aesthetic conservatism. What has changed is the increased visibility that the gallery context and the network of art biennials offer him. There has always been a risk of his films being decontextualised and exoticised when shown to audiences in the West, who might view Wang’s China with distanced and fetishised curiosity (though a large community of spectators has never existed for his work in China, where his films lack approval from the censors and cannot be publicly screened).

The fact that Wang been so enthusiastically received by the Western artworld, and only afterwards exhibited in Chinese galleries, reflects a move by the art establishment to confront social phenomena in ways that documentary cinema has been doing for decades (the case of Documenta 14 and its attempts – however limited – to intervene in the discussion around vulnerable populations of migrants in Europe is an obvious example). Across his body of work, Wang has tested the limits of cinema and explored the possibilities opened up through the extreme duration of his works and their unflinching confrontation with social suffering. From its start, filmmakers sought to document labour and industrialisation; Wang’s work can be seen as a timely return to that sensibility.

From the Spring 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia