Tishan Hsu’s early work provokes a strange corporeal response that speaks directly to the experience of inhabiting a body in a digital age. The unidentifiable orifices, limbs and proxy-organs in his paintings of the 1980s and 90s fuse seamlessly with glitchy cybernetic grids, while the sleek ergonomic curvature of his sculptures evokes body parts, computer screens and office furniture. Hsu’s works could be considered bodies in their own right, but also assert an almost corporate objecthood when you encounter them in person (that corporate and corporeal are cognate only makes the status of these objects as physical things – to be sold or inhabited – more ambivalent).

By rendering technology as the interface where representation and abstraction intersect in both art and life, Hsu proposes a radically alternative approach to the body and its politics, beyond the boundaries of what we understand as ‘physical’ and ‘virtual’, carbon and silicone, flesh and soul. This perspective makes 1980s works such as Head (1984) – an eerie flesh-toned, wall-based landscape of bodily holes rendered in lumpy Styrofoam and acrylic – and Ooze (1987) – an imposing and alien interior rendered in turquoise tiles – seem hyper-contemporary more than three decades after their completion, at a time when digital systems have encroached further into the experience of being human, and techno-bodies such as cyborgs, robots and avatars are being created, debated and politicised with ever greater speed.

While echoing the historical preoccupations of much cybernetic art of the past 30 years, Tishan Hsu has remained outside its canon. Born in Boston and raised in Switzerland and Wisconsin to Shanghainese immigrant parents, he started making art in his teens but chose to study architecture at MIT before moving to New York in 1975. There he encountered Pat Hearn, the Boston ex-punk and emerging gallerist, who had just set up shop in the East Village. As part of a programme including Milan Kunc, Peter Schuyff and Philip Taaffe, he inevitably became affiliated with the resurgence of painting of the 1980s variously known as neo-geo, neo-pop or post-abstraction – genres generally shunned by the critical art establishment, who saw them as cynically reducing abstraction to pure decor, to kitsch. But while evoking a politics of simulation similar to that of, say, Taaffe, Hsu’s work aligns more closely with predecessors such as Bridget Riley, concerned with examining the effect of the body moving through and across optical planes – such as paintings, for example, or computer screens.

Hsu’s emphasis on affect, indeed, couldn’t be further from the cold simulationism of his contemporaries: the work is intimate, personal and in continuous dialogue with the body. As a graduate, Hsu worked as a word processor at one of the city’s earliest office jobs involving a computer, and it is this now-ubiquitous experience – existing in front of a monitor – that would produce the conceptual basis for much of his work. Bodies morphing into hardware can be seen in works such as Lip Service (1997), in which TV screens become a part of a larger corporeal entity. Inversely, in Virtual Flow (1990–2018), bodies appear as silkscreened medical images (sourced from hospitals) within clinical glass boxes on a steel cart, mutated by skin-toned craters and lumps. That the unsettling structure – half medical cabinet, half body – extends to a standard electrical socket brings the trope of being ‘plugged in’ to an abject extreme.

The appearance of white noise, glitches and dislodged body parts adrift in the grid is reminiscent of the ‘cyberpunk’ aesthetics of the early 1990s, which similarly worked to articulate anxieties and fantasies about a uncertain digital future. But while much cybernetic thinking from this era imagined the web as a form of life privileging the immaterial mind (and thus doing away with the body), Hsu’s work insists on the fundamental corporeality of our encounter with such virtual systems. The body figures here not as some disposable prosthetic, but as a kind of interface, a place that connects various systems of reality. “I have always had certain doubts about the ‘transition’ from the body to the virtual,” Hsu tells me in his Brooklyn studio. “There is a tendency to default to the image of the body we have inherited, but what we experience ontologically and cognitively opposes that quite directly.” In the Interface series of inkjet prints from 2002, for example, Hsu began to present body parts in warping grid systems, forming a kind of skin that resembled a digital screensaver. He describes it as an attempt to “explore a different kind of ‘embodiment’ than art (Western or non-Western) had portrayed” that could reflect “the impact of technology on how the body located itself in the world”.

This bodily discourse – stripped of markers such as gender, sexuality and race – is a far cry from the representational identity politics of the 1990s. Hsu’s posthuman approach to the body echoes the work of more recent scholarship by theorists including Rachel C. Lee, who in her 2014 book The Exquisite Corpse of Asian America veers away from a conventional biological understanding of race to explore a more fragmented and distributed material sense of Asian American identity, informed by chemical, informatic and cybernetic flows. While one of the few successful Chinese-American artists of his time, Hsu never joined its roster of names in the canon of American art-history, in part, perhaps, because his art did not foreground his ethnic identity (one could think of Simon Leung, for example, a contemporary of Hsu, who also started at Pat Hearn Gallery). In fact, his prophetic biocybernetic perspective struggled to find its audience. After a few years in Cologne during the late 1980s, Hsu, disillusioned, retreated from the commercial artworld and acquired tenure as a professor in fine arts at Sarah Lawrence College in upstate New York.

The death of his mother in 2013 caused Hsu to reconsider his heritage and its relevance to his artistic practice. Perusing her possessions, Hsu discovered a collection of letters between his mother and her family in China dating back to the 1950s and 60s. Separated by the communist revolution of 1949, which prohibited Hsu’s parents from returning to Shanghai, the letters spoke of persecution, suicide and survival as well as the more mundane aspects of everyday life; a winding social history of which Hsu had been totally unaware. So he set out to track down and reconnect with the extended families of his late parents. Taking up residence in Shanghai for three, then five, then six months at a time, Hsu became absorbed by this newly discovered social and historical context and spent several years examining its material remnants, particularly the family’s rich image archive (a result of his great uncle’s passion for photography).

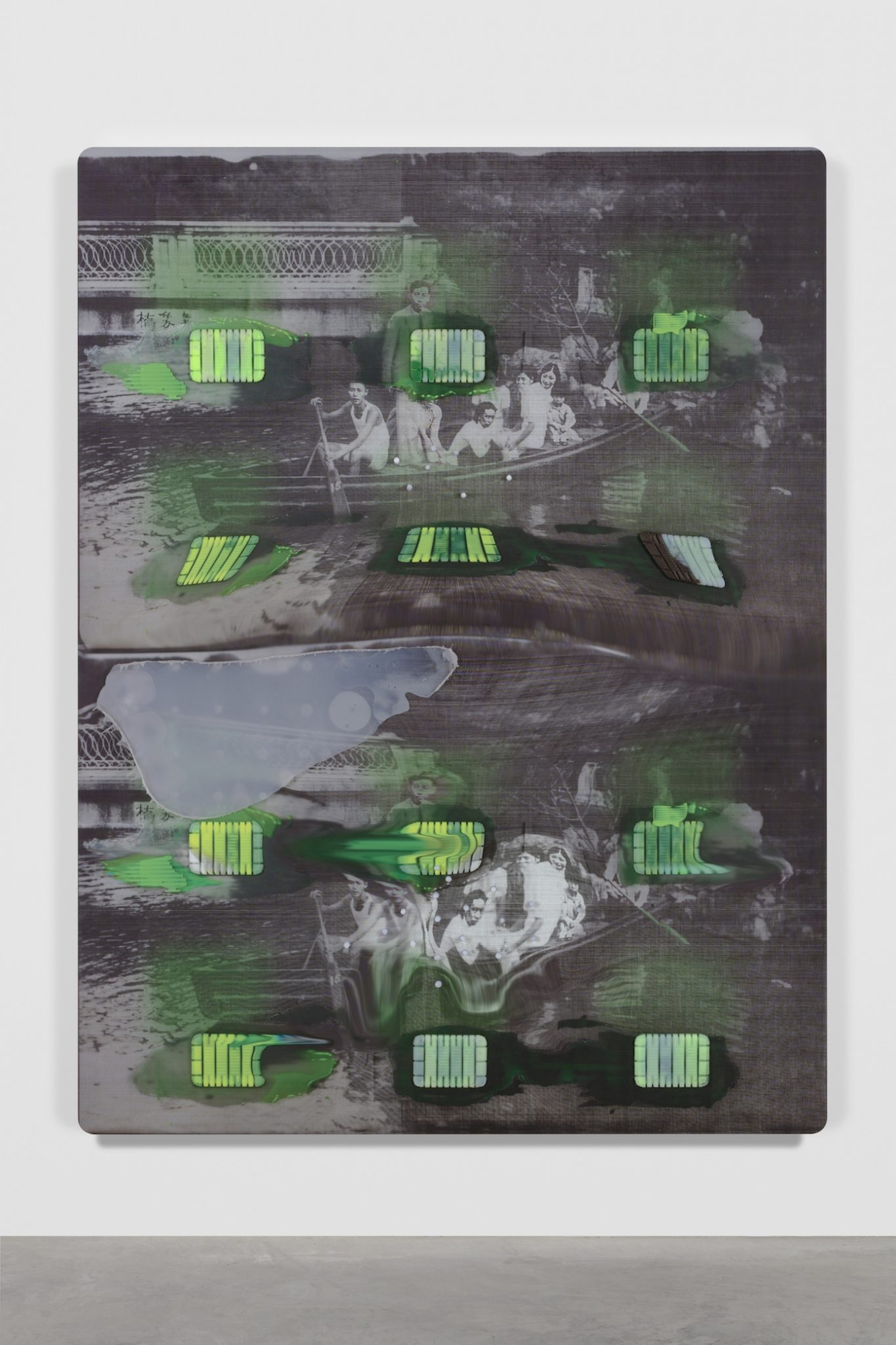

Elements of this archive appear in Hsu’s rounded aluminium print Boating Scene – Delete (2019), part of a new body of work referred to simply as The Shanghai Project, featuring a bucolic boating scene with an impeccably dressed family, a rare document of prerevolution Shanghai from the 1930s. Double Ring – Absence (2016), also an aluminium print, features scanned pages of a photo album, with many of its images seemingly ripped out. This pictorial absence speaks to the rigorous governmental censorship of the time, as any representation of bourgeois life was carefully and systematically erased by the city’s Red Guards, as well as the absence of this family history from Hsu’s own life. Hsu labours these images or absent spaces through a variety of present-day scanning, editing and digital reproduction techniques, accentuating their eeriness as alien historical documents: the layers of affect, lost and retrieved over time.

How does genealogy and family history translate into data? As always, it is the circulated information embedded in the virtual that constitutes the actual ‘material’ of Hsu’s practice. While his early work simulated a digitisation of the image, his new work emerges directly from it. “The whole reason I could do this project is because of technology, because of the Internet,” he points out. By mining a lost experience of familial trauma through digital communication – email, Skype and Whatsapp exchanges with his Shanghai family – and by processing the material remnants through digital image-making and editing, Hsu again renders technology as a space in which to negotiate identity, the body and history. “Somewhat ironically, it is the technology of photography in the twenty-first century that is not only enabling me to make any connection to but in fact has made me aware of the absence in the first place.” This absence – this personal data loss – speaks to how cultural memory lives, dies and recoups itself, even in today’s photo-saturated, digital and seemingly ‘connected’ culture. Through the suggestive aesthetic of tech, familiar diaspora themes such as cultural memory, trauma and social histories are rethought through digital and technological metaphors. “It’s kind of about information and the personal,” he adds. “And how the personal registers through technology; what is coded, stored, and what is not.”

While evoking the critical strategies of quintessential identity-based art practice – memory, trauma, personal archaeology – Hsu regards The Shanghai Project as an extension of his life’s practice, although its reference to Asian bodies is, he acknowledges, a ‘radical step’. After consulting its local artworld, Hsu estimated that showing this more personal body of work in Shanghai would be too politically risky due to the contentious status of the history of the revolution. Hsu believed that first showing the work in the US would entail its being read, against the artist’s wishes, as a statement bound up in identity politics, so for some time it seemed likely that the project would remain permanently in storage. But when an opportunity arose in Hong Kong, it seemed to make sense. The Chinese Civil War of the 1940s resulted in mass immigration from China to the then-British colony; even now a third of the city’s population is of Shanghainese origin. “This resonates with my own position as an Asian American who is showing work for the first time in Asia,” he concludes. “I am an in-between, a hybrid of being inside of the outside in China and outside of the inside in America, if you will.”

Tishan Hsu: Delete is on view at Empty Gallery from 26 March through 25 May

From the Spring 2019 issue of ArtReview