Widely spoken in Dakshina Kannada and other coastal districts of the southern Indian state of Karnataka, where it is an important cultural marker, Tulu is deemed a ‘minor’ language by the national government. It is curious for several reasons that it should not be counted among one of the country’s 22 official languages. With its sophisticated orature and antiquity, stretching by some accounts back to the third century BCE, Tulu is among the most cultivated of Dravidian languages. It is also unusual, in a landscape where several languages coexist (though not always peacefully), for one language to inform and influence the everyday so broadly.

Tulu is rooted in Karnataka and Kasaragod, a small district within Kerala’s borders, a collective area once informally known as Tulu Nadu. Though a movement to formally group these areas under that name gathered strength during the 1940s, the demand had lost steam by the time Indian states were reorganised along different linguistic lines under the States Reorganisation Act in 1956. Today the language has an estimated five million native speakers, give or take a few hundred thousand counted in the census as Kannada speakers because they live outside Karnataka. A spoken language that is typically transcribed in the Kannada alphabet, Tulu is the language of the folk deities, and popular theatre like Yakshagana, mass media, community events, politics and everyday commerce are all informed by it. The language gave the region its wide array of semidivine beings and seasonal rituals.

Distinct from folk deities, these spirits traditionally fulfil the role of protector and conservator of the forested lands belonging to them. Trees in these sacred groves – called devara-kadu in Karnataka and kaavu in Kerala – cannot be cut without angering spirits with personalities ranging from polite and benevolent to short-tempered and demanding. Historically, these protected areas helped to preserve important trees and medicinal plants, and every year, after the harvest, villages arrange for events – called, depending on its purpose, Bhuta Kola, Hulivesha, Nagamandala, Bhootaradhane and so on – where the spirit possesses a member of the community, almost always a man. What follows is a dance-drama during which the spirit answers the villagers’ questions, resolves conflicts and is appeased with alcohol, food and other offerings. Given Tulu’s inescapable presence, scholars grouse that it has not been granted the status it deserves, either in Karnataka or nationally.

In recent years, efforts have intensified to have Tulu recognised in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India, which would make it an official language. The Karnataka Tulu Sahitya Academy, set up by the Karnataka government in Mangalore in 1994, has made many uncontroversial and commendable contributions to these efforts, but it and other proponents have also put forward a contentious plan to give Tulu a script of its own, something it has not had in many generations. In addition to the politics of binding a rich oral language to a standardised alphabet, such a move raises questions about what a language gains and loses in the process.

Surendra Rao and K. Chinnappa Gowda, retired professors in the departments of history and Kannada, respectively, at Mangalore University, are collaborating on a long-term project to translate Tulu works into English. So far, they have published five books, ranging from novels to anthologies of poetry, folktales and folksongs; a forthcoming translation represents an early form of fiction, what Gowda calls a ‘pre-novel’. There are as many varieties of Tulu as there are communities and socioeconomic classes that speak it. ‘There is nothing like the tyranny of standardised Tulu in operation,’ the academics write in an introduction to one of their books, all of which draw from literature, oral and written, that developed across the social spectrum.

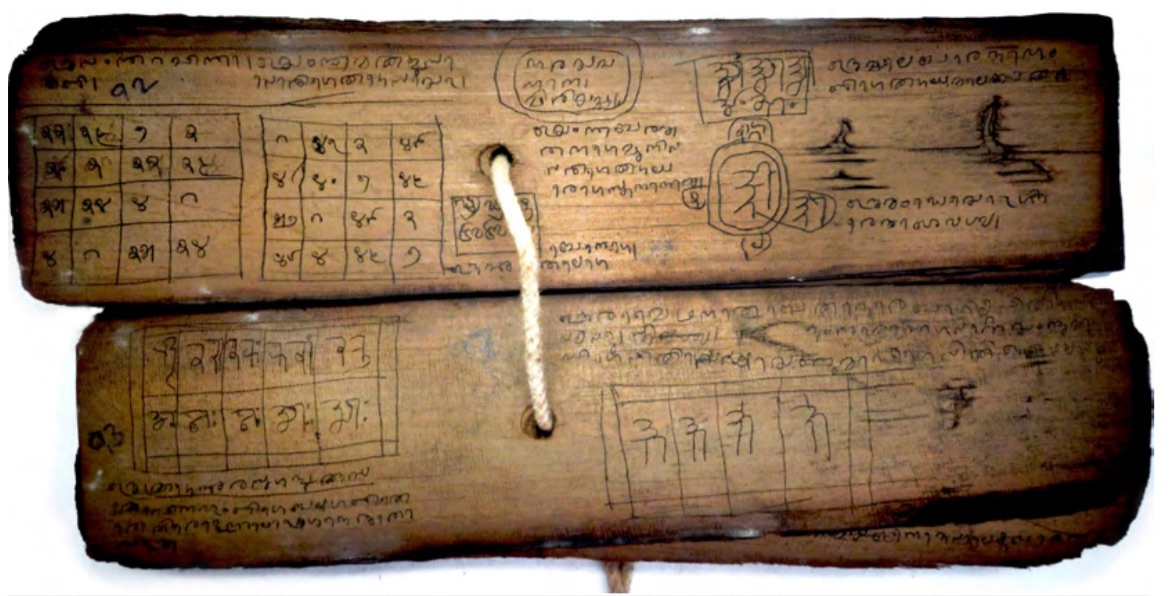

Speaking to me from the United States, which he is currently visiting, Gowda discussed the status of the language and its influence over parts of the Konkan coast of western India. Interest in the idea of Tulu Nadu and in the lives of its people was renewed during the 1970s, he told me, when subaltern studies, the writing of history from the perspective of the people rather than the elites, was becoming popular as a narrative. Tulu had by then been written in the Kannada script for many decades. “Tulu had a script once but it was sparingly used, mostly to write religious and occult texts on palm leaves, centuries ago, which were not meant for a general audience and needed to be restricted to a choice few. Tulu developed as an oral language, and is very rich because of that,” Gowda continued. Tigalari, or Arya Ezhuthu, as the Tulu script is called, did not get administrative support within Karnataka and was not taught in schools, nor were many popular books in the script in circulation, for which reasons it fell out of use by the mid-nineteenth century. Even religious texts were no longer written in the script by then. Through a series of sociopolitical and cultural migrations, the script travelled south to Kerala and developed into what is now the Malayalam script.

One version of a new Tulu script – loosely based on Tigalari – is now being taught in schools in the region. While scholars of the language support its teaching in principle, many object to how the script has been formalised and introduced. Writing a few years ago, professor Radhakrishna N. Belluru detailed the organic way in which a script develops, highlighting this as a means of demonstrating how taking the centuries-old, barely used Tulu script and changing it abruptly to suit modern usage overwrote accumulated meaning in the spoken language, setting it back by decades. The script now being taught in schools is ridden with flaws and is unscientific, say script researchers, adding that it was approved without the consensus of writers, scholars and cultural practitioners, as is the norm.

The real question, though, is whether a language needs a script in the first place. Taltaje Vasanthakumara, retired professor of Kannada at the University of Mumbai, is from, and now lives in, Dakshina Kannada district. Speaking to me about scripts and languages, he said that if a language already had a script, it should naturally be used, preserved and developed. “But a script is only complementary to a language. English or Hindi don’t have their own scripts. Konkani uses two scripts – Devanagari or Kannada – depending on whether you are in Goa and Maharashtra or Karnataka. While we have to wonder who we are to pass judgment on whether a new script is needed or not, most Tulu speakers are not aware of the script it once had,” he said.

Gowda too questioned whether a dedicated script was either necessary or inevitable. “With Tulu, it is neither. The language is not endangered, and is well adjusted as a language written in the Kannada script,” he said. Even if a new script is taught in schools, it takes decades to catch on: learning, teaching and developing a script cannot be achieved in one or two generations, both professors agreed. Narrowly connecting the value of a language to whether or not it has a script is contrary to how linguistic history has been conducted the world over. For Gowda the problem is that language is traditionally taught by a script, to which he said, “Leave the script, teach the language. To say script is necessary is detrimental [to the development of a language]. Orality is where the essence of language exists. Indigenous knowledge is disseminated through speech. In the context of Tulu, it is the language of knowledge and it cannot be separated from life.”

So why is there a hurried drive to introduce a script instead of working on the language itself? These scholars refuse to speculate, but hint at political reasons – the Tulu-speaking business community is a wealthy and influential voter bloc: there is much money involved in the long path to getting a ‘minor’ language nationally recognised.

One of the requirements for being declared an official, classical language is that it should have a long literary tradition. There is no necessity that it be only a written tradition. The Tulu lexicon has over 100,000 words, meaning that the language is well developed. “Orature is just as important,” explained Gowda, emphasising that Tulu’s beauty, essence, nuance and thus power to influence lay in its orality. “Tulu is a very rich language. It is a living, breathing thing. While our translation efforts are intended to build a body of work [in English, because it provides wider readership] to help the language be included in the Eighth Schedule, to focus on a discontinued script is doing a disservice to Tulu,” he said.

To confine an otherwise thriving language to a script to which it no longer has an organic connection is counterproductive. Vasanthakumara equated it to the museumification of the language and, by extension, to arresting the influence it has on the people that keep Tulu alive and thriving.

From the Spring 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia