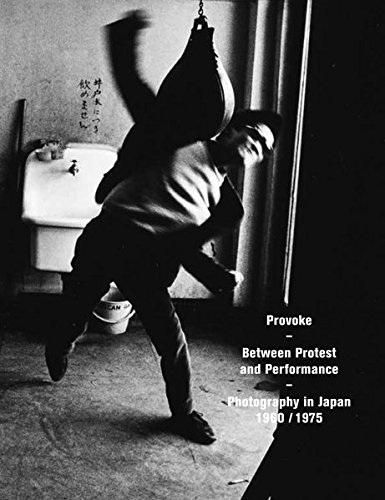

The period between the late 1960s through the 70s – the last decade of large-scale political movements in Japan – is usually considered to be the golden age of Japanese photography. One of the most influential publications during that time was Provoke, which featured new work by photographers and writers. Although it ran for only two years and three issues (plus a compilation) it was such a seminal magazine that the ‘Provoke era’ is now used to describe the postwar avant-garde, defined by their experimental attitude and Are-Bure-Boke style, which is blurry, grainy and out-of-focus black-and-white photography. Since then, the work of many former Provoke members such as Daido Moriyama and the late Takuma Nakahira have been widely exhibited and, in Vienna this January, the first major touring exhibition of Provoke opened, accompanied by a book, Provoke: Between Protest and Performance, which not only reproduces pages from the magazine, but provides it with a historical context.

Provoke was launched in 1968 by photographers Takuma Nakahira and Yutaka Takanashi, critic Koji Taki and poet Takahiko Okada. As seen from the diversity of its participants’ occupations, the magazine did not restrict itself to showcasing photography, but aimed to create, as stated in the inaugural editorial, ‘provocative materials for thought’. Moriyama joined the collective from the second issue, but after publishing the third issue, and a final compilation, the group broke up. Provoke’s iconic status, both at home and internationally, is a result of the experimental nature of the artwork it featured and the unique approach of allowing photography to bump into thoughts and politics, and generally mix together. Or, as explained in the introduction to this book, Provoke arguably bound photography to political and social protest on the one hand, and to avant-garde performance on the other. It was not a photography magazine nor a photography critique, but rather a radical act of defiance against dominant forms of art, politics, philosophy and criticism, and against society of that time.

This volume’s three sections (‘Protest’, ‘Provoke’, and ‘Performance’) draw a picture of the historical and intellectual backdrop against which Provoke was born. The first chapter, ‘Protest’, contains images and texts from other protest photography books from the 1960s and 1970s, and maps the intellectual territory for Japanese protest photography. In ‘Provoke’, most of the pages from the first three issues of Provoke magazine are reproduced. Moreover, this extends to spreads from important photobooks subsequently published by the original Provoke photographers: among them, For a Language to Come (1970) by Nakahira, Farewell Photography (1972) by Moriyama, and Towards the City (1974) by Yutaka Takanashi. The final chapter ‘Performance’ attempts to link protest photography to performance by focusing on performance groups active from the 1960s onwards and the use of photography in performance art. As is mentioned in the preface to the book, protest is not performance, but under certain circumstances the two activities are closely analogous and so is Provoke.

The present volume is a must-read for those who study Japanese photography and avant-garde art movements. Provoke-era fans will be especially satisfied, as this is the first book that includes so many images of important, but hard-to-get photobooks with translations of crucial texts and interviews. However, this volume will also appeal to those who have never heard of the movement, for the way it simultaneously captures the movement in overview and zooms in on interesting details.

However, it must be said that, especially in Western countries, the movement has been somewhat idealised over time. As Koji Taki said in 1993, it was iconic but not the only movement in play during that period of transition; additionally we need to look at the movement in terms of societal change since then. What might be more interesting still is a reconsideration of the movement from a contemporary point of view, in order to investigate what kind of legacy has been left to subsequent generations.

This article was first published in the Summer 2016 issue of ArtReview Asia.