Selected by Mark Rappolt

Already one of the more prominent and influential artists in his native Sri Lanka, Jaffna-born and -based Thamotharampillai Shanaathanan produces art, often hung upon an archival framework, that is firmly rooted in the specifics of the immediate and the personal – in this case the lasting impact of Sri Lanka’s three-decade-long civil war – but which nevertheless opens itself up to more universal concerns. And among other things he is also a cofounder, in 2014, of the Sri Lanka Archive of Contemporary Art, Architecture and Design (SLAAAD), a unique entity on the island.

A conflict? An artist? An archive? A ‘periphery’? What a cliché! Hold yer horses; this ain’t like that. Shanaathanan excels at manifesting complexity in apparently simple forms. His works remain relatively free of the Gordian knots of indecipherability and pretentiousness that bind so many of the artworks produced as part of art’s current archival obsession. Cabinet of Resistance 2 (2016), exhibited during the recent Kochi-Muziris Biennale, is an old-fashioned piece of furniture housing a card index divided into 30 drawers. It’s so unassumingly quaint that it’s easy to miss. The drawers contain simply-typed cards that by and large detail the ways in which ordinary Tamils adapted over the years of conflict and suffering (the war ended in 2009). We learn about recipes for traditional dishes being adapted due to a shortage of potatoes (during an economic embargo on rebel-held territories in the north of Sri Lanka), about converting petrol vehicles to run on kerosene and about using saris to make sandbags. Under the entry for printing press in an earlier version of the work is this: ‘although my elder daughter helps me in page making. I do not have sons who can inherit my business’; whether that’s for natural or unnatural reasons is left unsaid. But while this is, without doubt, a record of the hardship (burials and missing children also feature in the accounts) and suffering of war, it is superseded by its being a record of resilience and adaptability. It’s a resistance to passive victimhood, if you like.

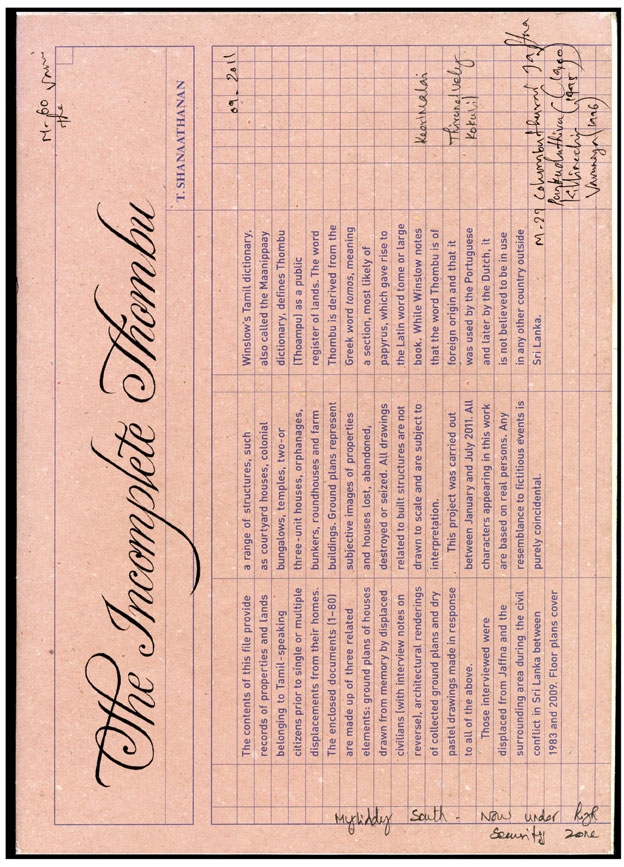

Shanaathanan’s best-known work to date is The Incomplete Thombu (2011, commissioned by publisher Raking Leaves), a book that takes the form of a land registry (thombu in Tamil means a public register of lands, and, speaking of adaptation, although the word is unique to Sri Lanka, it comes to the island with Greek origins via the Portuguese and the Dutch). In it, Shanaathanan records 80 memories of the homes and houses that Tamil-speaking Sri Lankans, displaced by the conflict, left behind. Each home is represented by a sketched floorplan made by the interviewee; a cleaned-up version drawn by an architect (sometimes slightly, sometimes more noticeably different); these are interspersed with written statements recording the memories and histories that the interviewees associate with a sense of their home (among them: the smell of flowers, recollections of family members, a sense of anxiety or insecurity, lost horoscopes), illustrated by Shanaathanan’s own drawings. While the work is both a contrast and reconciliation (in the accounting sense too) of what people took with them and what they left behind, The Incomplete Thombu is also, as the artist confesses, a way by which he can interrogate his own story and his own experiences of the land.

Shanaathanan is based in Jaffna. The first part of his Cabinet of Resistance project is on view at the Asia Art Archive Library in Hong Kong.

From the Summer 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia, in association with K11 Art Foundation