From 2017: The Indian artist on how the past activates itself in the present moment

In 1998 the Indian government carried out a series of underground nuclear tests in Pokhran, a northern province in the desert state of Rajasthan. The test site was only 150km from the border with Pakistan, and by this time India had already engaged in three separate wars with its neighbour. In the same year, artist Nalini Malani made a work entitled Remembering Toba Tek Singh (1998), based on a short story by Sa’adat Hassan Manto, an Urdu author and playwright from the new Pakistan. In the short story, Hindu and Sikh patients from a psychiatric asylum in Pakistan are filled into coaches to make the journey over to India, and bizarre circumstances ensue. A patient climbs a tree and decides to remain there instead. Others occupy narrow strips of land yet unassigned by cartographers. Politics is posturing, and Partition is madness. In Malani’s four-channel video installation, first presented at the Prince of Wales Museum in Mumbai in 1999, visitors entered a room with a Mylar-covered floor and 12 tin trunks stuffed with quilts and small, flickering monitors displaying found footage. A woman’s voice hangs over the work as she reads out an extract from the short story, and the figures of Remembering Toba Tek Singh spill and melt into each other, drifting along the installation’s several materials.

“History does not occur in episodes,” Malani declares. When asked about her relationship to Partition, and the narrative of trauma and displacement that is often applied to her work, she continues, “I am more interested in how Partition activates itself in the present moment.” When referring to the events of 15 August 1947, Malani says “Partition/Independence”, as though the two words are interchangeable. She is often described as a Pakistani artist, but was born in Karachi in 1946 before the country was even formed. In 1947 her family was forced to leave for Calcutta (now Kolkata). “I have never had the desire to go back to the cities and villages my parents were from,” she says. “But my mother, at ninety-six, still talks about it. It is not my trauma, but I have grown up with the smell of those cities. Their aura.”

In the polyptych Cassandra (2009), Malani paints her figures onto acrylic sheets with ink, enamel and acrylic paint. Malani’s method of approaching surfaces is tactile: she will stain figures out over transparent sheets or smudge them into shape. For Roobina Karode, director of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi (which hosted Malani’s 2014 retrospective You Can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag), this is a language that suits “unpaintable and sometimes unpalatable themes, such as innards flying across a plane to depict the violence inflicted upon women’s bodies”. In Search of Vanished Blood (2012), a six-channel video/shadow play with five rotating reverse-painted Mylar cylinders, broken figures float along the work’s surrounding walls in a loop. Malani plays with scale, often combining very large pieces with smaller fragments, and her works may be read as surfaces of assembly, shifting between mediums and materials. They are innately theatrical and almost always rely on movement. It is a clever strategy; “People in India understand the moving image so well”, she says.

As a student, Malani received a very traditional training in painting at the J.J. School of Arts in Mumbai. An early introduction to film, however, radically changed her practice and led to her becoming one of the first female South Asian artists to work extensively with the medium. Between 1969 and 1971 Malani was a member of the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW) convened by Akbar Padamsee, one of India’s better-known painters. Padamsee used state funds he had received in the form of a Nehru Fellowship, matched by his own money, to set up the initiative, a rare piece of artistic infrastructure designed to enable experiments with technology. Set in his Bombay apartment, Padamsee brought together painters, printmakers, animators, sculptors, cinematographers and even a psychoanalyst, and the workshop aimed for a multidisciplinary exchange. Malani and painter Nasreen Mohamedi, who had a practice of geometric abstraction, were the only two women to be included in the workshop, where Malani was its youngest participant.

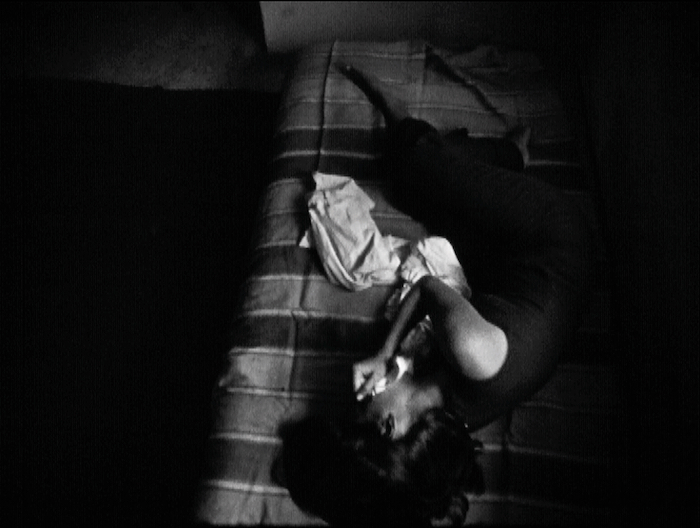

Malani made a series of 8mm and 16mm films, working with great speed as she produced three films in the short span of six months. These three films have only recently been discovered. In Still Life (1969) the camera trails the possessions flung over Malani’s bed, giving the viewer an intimate look at her private space. In Onanism (1969) Malani uses a ladder to simulate a crane shot to film a woman suffering a series of violent contortions from above. The third film, one half of what then became Utopia (1969/76), was a work of pure abstraction. Malani built an urban landscape from thick black card and photographed it from erratic angles. She then converted these photographs into large negatives, filtering in colours onto their grey and black tones. She then reshot these photographs on 8mm. The landscape rendered by this process is at once one of the modernist architecture it tries to emulate as it is its deconstruction: a series of simple photographic gestures. “For me, abstraction has always been a research material, or a process, that allows me to see further than just the surface,” says Malani, and in her work, abstraction becomes a useful device with which to negotiate the identity-making practices of a new country.

As an artist who began making work during the 1960s, during the rollout of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision for a new India, Malani grappled with Modernism – and a ‘Nehruvian Modernism’ at that. Modernism was the language chosen by Nehru for the new India, and Nehruvian Modernism was a narrative of progress: decidedly secular and pluralistic. It was also obsessed with the fashioning of the ideal modern subject. Malani was one of very few artists of the time to be cognisant of how South Asia was simultaneously enacting multiple Modernisms, and that several regions were approaching the modern subject differently: from the Bombay School to the Bengal, all the way down to Cochin. “We were thinking about the Indian figure, and how we could use our different local stories to connect with our audience, and with each other,” says Malani about her collaborations, as she worked closely with Nilima Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar from the Baroda School.

In the summer of 1979 Malani walked down Wooster Street in New York to visit the recently opened A.I.R. Gallery. Ana Mendieta was there – as were Nancy Spero and May Stevens, to whom Malani was introduced. Taken by the gallery’s fierce determination to create a space for the work of female artists, in a city whose galleries otherwise almost never showed female work, let alone women of colour, Malani returned to India with the aim of extending the formula. Such a space did not exist in India, and Malani speaks often about the patronising treatment she received from her male peers for most of her career. After years of negotiation with various public and private institutions, a show entitled Through the Looking Glass, featuring the work of Madhvi Parekh, Nilima Sheikh, Arpita Singh and Malani herself, travelled India between 1986 and 1989.

Malani has always been vocal about her feminism, which is at first interested in making women visible outside narratives of ‘femininity’. Her work often speculates the gestures and voices of women who have been silenced, particularly by ‘great’ works of literature, such as Sita from the Ramayana, whom she places alongside the Greeks Cassandra and Medea. In an ongoing series entitled Stories Retold (2002–) several paintings look to mutate singular female myths, most famously Sita/Medea (2006), in which both women, painted on Mylar with watercolour, acrylic paint and enamel, are fused together in many iterations along the same plane. “I find that we have so many parallels to Greek mythology, but still in the West I am always asked – why are you interested in Greek mythology? But I say we have a whole Indo-Hellenic school of sculpture all along Afghanistan, and the Bamiyan Buddhas are in the Hellenic style.” In Malani’s treatment of the world, nothing happens in isolation, and neither should it be considered as such. “When we’re talking about indigenous Modernism,” says Malani, “I think the failure is of a different nature – we were, and still are, too reliant on the West to determine our language.”

Malani’s 2014 exhibition at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art took the form of a nearly yearlong retrospective and marked the first time her work was shown on such a scale in South Asia. It was a significant moment in her career – her place in the history of Indian modernity was cemented, as was as her continuing contribution to the contemporary discourse in South Asia. The Centre Pompidou in Paris, where a retrospective of Malani’s work has just opened, has a room especially dedicated to the early films and photographs of 1969–76. Her films from 1969, Still Life, Onanism and Taboo, which have never been seen before, are the most significant in the show: where Malani deftly negotiates the politics of a nation at the brink of a new identity. She is also looking forward, and preempts how the Nehruvian idealism in which she herself was implicated was to fracture in the years to come. Malani’s practice epitomises the moment as succinctly as it delivers it – the new India was not simply one of idealisms, but also broken, ephemeral and composed of multiple narratives.

This article was first published in the Winter 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia