With Toshio Matsumoto’s passing in April (1932–2017), Japan lost one of its most rigorous filmmakers and trenchant film critics. Two recent exhibitions – Toshio Matsumoto: Everything Visible Is Empty at the Empty Gallery, Hong Kong, and Japanese Expanded Cinema Revisited at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum – offer a rare and timely opportunity to reexamine the prolific artist-critic’s oeuvre, which encompasses some of the most important moments of postwar Japanese art.

Matsumoto began his filmmaking career by planning, cowriting and assistant-directing Ginrin (1955), an astonishingly experimental PR film commissioned by the Japan Bicycle Promotion Institute. His collaborators on the project were Shozo Kitadai and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, members of Japan’s postwar collective Jikken Kobo, the composer Toru Takemitsu and the special effects creator Eiji Tsuburaya, who would go on to do the same for the Godzilla series. The film presents a simple narrative of a boy daydreaming about bicycles, while crystallising Jikken Kobo’s incorporation of everyday materials and innovative technologies as well as its predilection for sci-fi aesthetics and narratives that address the unconscious. Placed within Matsumoto’s oeuvre, it announces what would become his modus operandi – production from the interstice. With Ginrin, Matsumoto merged experimental aesthetics with commercial filmmaking. He would go on to similarly complicate distinctions between avant-garde and documentary filmmaking, experimental and narrative cinema, and artist and critic.

As much influenced by Luis Buñuel as by seminal ethnographer and folklorist Kunio Yanagita, the black-and-white The Song of Stone (1963) fuses documentary with surrealist strategies. Made contemporaneously with Chris Marker’s better-known La Jetée (1962), it also comprises nearly exclusively still photographs, which in Matsumoto’s film were shot by Ernest Satow. For Matsumoto, it was an interrogation of the film medium itself. If film is constituted by still images, what better subject to explore this nature of the medium than stone, which in the village of Aji in Kagawa by the Seto Inland Sea had sustained, taken and marked, as tombstones, the lives of local miners for hundreds of years? If motion and life can be created by suturing still images, the film effectively proposes, inanimate minerals can be brought to life through filmic poesis. “When a stone breaks unexpectedly,” the film tells us, “the men [of the village] mumble ‘stones are living things, stones are living things.’” Matsumoto insisted that film needed to address both external and internal realities. The combination of the solemn images of villagers working in the stone processing plants, the sombre narration addressing the villagers’ animist beliefs and Kuniharu Akiyama’s musique concrète soundtrack creates an uncanny effect. Through the uncanny, which Freud defined as the resurfacing of once-repressed content, Matsumoto exposes psychological truths that cannot be captured by neorealist documentation alone.

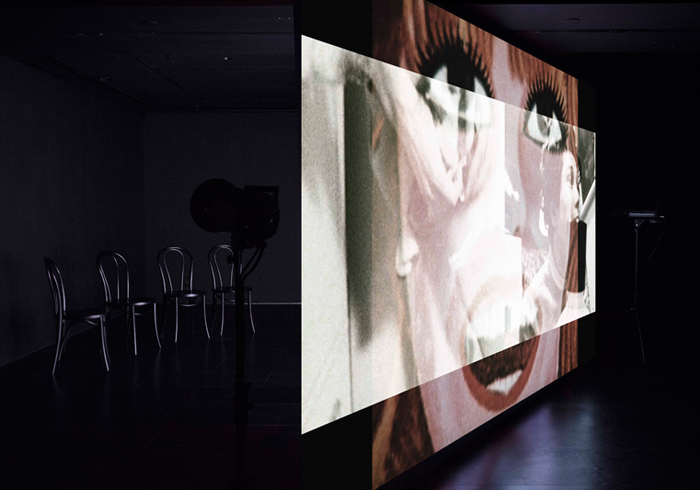

For the Damaged Right Eye (1968), faithfully (and very satisfyingly) reproduced as a triple projection at The Empty Gallery, is intended as a wakeup call, opening with the sound of a phone being dialled. Matsumoto saw a paradigmatic shift in the heady, heated, hopeful moment of simultaneous global uprisings of 1968, and staged his own by triggering the first Japanese film expanded to three projections. Designed to dismantle conventional aesthetic values, the film’s dual projection with a third laid over the centre of the two juxtaposed frames expands filmic space to stage an intense visual assault. At one moment in the film, flickering, seizure-inducing strobes fire at the audience. In 1968 smoke accompanied the strobes, purportedly striking panic in viewers, who would have been accustomed to seeing clashes between student radicals and cops on television, in photographs and in the streets. Rapidly cut shots of Tadanori Yokoo’s 1966 paintings of women, go-go dancing, protesting, cross-dressing, riot-policing, motorcycle racing and happenings are juxtaposed, looped, scratched and overlapped, and accompanied by the sounds of fuzz guitars and anthems, from Aretha Franklin and the Rolling Stones, to create a mesmerising and appropriately bewildering cacophony capturing the dizzying velocity and exuberance of the times.

In the following year, Matsumoto produced his most remarkable work, Funeral Parade of Roses (1969) – a narrative feature retelling the Oedipal tale as a love affair between a beautiful trans woman (‘Eddy’ played by Peter in his debut role) who works at a gay bar and her boss, who also turns out to be her father. At a time when contemporaries such as Nagisa Oshima, with whom Matsumoto also had an ongoing debate in the film journal Eiga Hihyo, were unquestioningly phallocentric, repeatedly using scenes of women being raped by men as metaphors for male political impotence, Matsumoto was criticised for privileging sexual minorities over real politics. How prescient he was in understanding that sexuality is political! Though most frequently noted for its queer narrative, the film might also be described as formally queer, as it incorporates animation, documentary, found footage and other experimental filmmaking techniques into its feature-length narrative framework. In this sense, For the Damaged Right Eye is also a study for Funeral Parade of Roses, with which it shares many visual tropes. For example, while the former documents an event orchestrated by Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver in Shinjuku Station’s West Exit Plaza, which briefly served as an agora for artists and protesters before being renamed West Exit Passage, after antiwar ‘folk guerrillas’ clashed with riot police in 1969, the latter shows the performance art group Zero Jigen carrying out the titular procession in the streets of Shinjuku.

Crucially, both For the Damaged Right Eye and Funeral Parade of Roses show young people negotiating their right to the city. If the 1960s were marked by efferent articulations in both art and politics with both avant-garde artists and political radicals taking to the streets, the failure to stop the renewal of the Japan–US Security Treaty in 1960 and again in 1970, and the institutionalisation of avant-garde art, marked by the 1970 Tokyo Biennale and Expo 70 in Osaka (where Matsumoto showed another multiprojection film, Space Projection Ako, from 1970) caused a deep sense of frustration for many on the left. Not coincidentally, Masumoto’s films of this autumnal decade turn to the subjective interior via structural experimentations. While the subject is approached critically and psychoanalytically, and through the matrices of gender and sexuality in Funeral Parade of Roses, it is addressed ecstatically and psychedelically in his works of the subsequent decade.

Matsumoto’s most successful films of this period are the relentlessly pulsating Atman (1975), shot on infrared film primarily through stop-motion, as the camera revolves around and zooms in and out on a seated figure in a noh-theatre hanya mask in a flux of exposures and colours; and Everything Visible Is Empty (1975), which rapidly and spellbindingly intercuts Chinese characters constituting the heart sutra (called hannya shingyo in Japanese) and images of Hindu deities and mandalas shot in contrasting acidic colours. Both films are set to soundtracks composed by Toshi Ichiyanagi – Atman’s is electronically composed and eerie, while Everything Visible Is Empty’s combines a relentlessly driving rhythm with the sounds of a meandering sitar. Aesthetically, the latter film resonates closely with contemporaneous musical output by Takehisa Kosugi and his Taj Mahal Travellers as well as the collaged album covers Tadanori Yokoo made for Santana (especially Lotus in 1974): all of them looked to India for Eastern spiritualism and a way to overcome the overbearing influence of Western Modernism.

While aesthetically compelling, it’s hard not to see these and Matsumoto’s subsequent output of the 1980s as a retreat, respectively, into the interior and into purely formal experimentations. In this context, Atman’s rapid zooms metaphorically represent the difficult negotiation of interior and exterior engagement. While Matsumoto strove to express both, the coincidence of formal, political and subjective experimentation was only realised momentarily at the end of the 1960s. The explosive, radical energy captured in For the Damaged Right Eye and Funeral Parade of Roses are regrettably viewed nostalgically in Japan. It may have more contemporary relevance in Hong Kong, where – as poetically remembered by Pak Sheung Chuen at his current exhibition at Para Site – in February 2016, citizens in the Mong Kok clashes expressed their right to the city by freeing bricks from the pavement and throwing them at the authorities, performatively realising a popular slogan of May 68, ‘beneath the pavement, the beach,’ and precisely the kind of overturn of values Matsumoto had in mind when he made those films.

Taro Nettleton is a writer and critic based in Tokyo.

From the Winter 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia