Eisa Jocson’s fearless performances explore the politics of the gendered body, the migration of labour, the cultural impacts of the ‘happiness industry’ and the conditions of the Filipino diaspora. In Princess Studies (2017) two Filipino performers – one female, one male – in the fancy dress costumes of Disney’s Snow White (1937) move through a concrete space, performing synchronised movements and speaking (mostly) in unison. Their words and actions phase into a repetition, resembling some kind of sinister rehearsal before, an hour or so into the performance, the princesses inhale deeply and shout:

“What do you do when things go wrong?”

“I’m awfully sorry, I didn’t mean to frighten you, but you don’t know what I’ve been through. And all because I was afraid… I’m so ashamed of the fuss I’ve made…”

The audience is silent. Leaning against a wall at the back of the room, I feel uneasy and defensive. This is less a performance of the typical Disney princess – inevitably rescued by the masculine hero – than about the social pressures to perform happiness. Indeed, Princess Studies is the first part of HAPPYLAND (2017–), a series of performances whose title refers both to the slogan used by Disney for its themeparks (‘the happiest place on earth’) and the name given to a densely populated slum in Manila. As such, it hints at the preoccupations with identity, entertainment as labour and migration underpinning Jocson’s highly politicised practice.

HAPPYLAND has toured institutions and festivals across Asia and Europe, including, in the summer of 2019, the Koppel Project Central in London, where it was presented in association with a group exhibition at SOAS featuring 11 artists working in the Philippines. Curators Renan Laru-an, Merv Espina and Rafael Schacter proposed to ‘chart the historical and contemporary forces linking this archipelagic chain with other key spheres of global power… by placing the theme of belatedness as a principal concern’.

This idea of ‘belatedness’ as shedding light upon the power relations of the postcolonial Philippines fits neatly with Jocson’s ‘princess studies’ and its focus on the body, new-adult fiction, fantasy production and labour migration. In a recent discussion with ArtReview Asia, Jocson explained how Disney serves as a useful case study for these issues: Filipino workers train for years to gain qualifications as dancers so that they can be employed at themeparks including Hong Kong Disneyland. Happiness, at least in its commodified form, is predicated on migrant labour and unequal employment conditions.

Trained in Manila in choreography and with a background in ballet, Jocson used her own experience of entering (and winning) pole-dancing competitions to create her 2011 performance Death of the Pole Dancer, in which a discipline traditionally understood as being for the benefit of gendered voyeurs was transformed into an act that questioned the politics of female expression and spectatorship. She subsequently committed herself to learning ‘macho dancing’ – a highly coded form of male erotic dancing – which she turned into the performance Macho Dancer (2013), another to challenge both fixed gender positions and the power dynamics of watching and performing.

The emotional and physical labour of the Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) employed in industries including erotic dancing resonate through Princess Studies. By collaborating with male actors (including the Filipino performance artist Russ Ligtas), Jocson subverts the dominant fairytale narrative, playing on issues of both race and gender: in 2017 she worked closely with four professional dancers on the second part of HAPPYLAND, entitled Your Highness, which applied avant-garde choreography to a study of Disney’s archetypal princess figures, including Ariel (from The Little Mermaid, 1989), Belle (Beauty and the Beast, 1991) and Giselle (Enchanted, 2007). By linking the Western ideal of the princess to the work of Filipino migrants acting it out for money at themeparks, Jocson destabilises the fantasy of whiteness that they are being asked to perform. Princess Studies dramatises these issues of Filipino identity in the ‘doubling’ of its performers.

This is less about resisting the lure of foreign employment than about highlighting labour conditions for those working in the entertainment, services and arts sectors (the separation between which Jocson’s work also interrogates). According to a 2011 report by the Asian Migrant Centre and the Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA), the Philippines is the second largest exporter of labour, with ‘ten percent of the population leaving the country to work in various parts of the globe’. With this has come a rise in online counselling for members of the diaspora experiencing homesickness, shame, loneliness or depression, and so HAPPYLAND is also a study of what happens when the fantasy of leaving home is not matched by the reality. This complex representation of the diaspora experience retells the story of a princess/artist/worker for Filipinos abroad, and reconsiders the oppressed ‘other’ of Western colonial histories in the context of a new world of globalised labour.

Princess Studies uses a form of mimetic protest through which to challenge cultural norms. The synchronicity and mimicry acted out by Jocson and her male collaborator in this work reminds us that the bodies of entertainers are at once replaceable (in the sense that they are parts in a capitalist production) and unique (because they express an individual subjectivity). While searching through the harsh realities of today’s entertainment industry, Jocson continually acknowledges everyday racism and the specifically Southeast Asian context of postcolonial studies of inequality within the migratory ethnoscape. Her practice continues to expose Western conceits of the entertainment industry in its relations to migrant labour. By using the body as an instrument of artistic expression and political protest, Jocson challenges the reduction of the migrant labourer’s body to the status of an object.

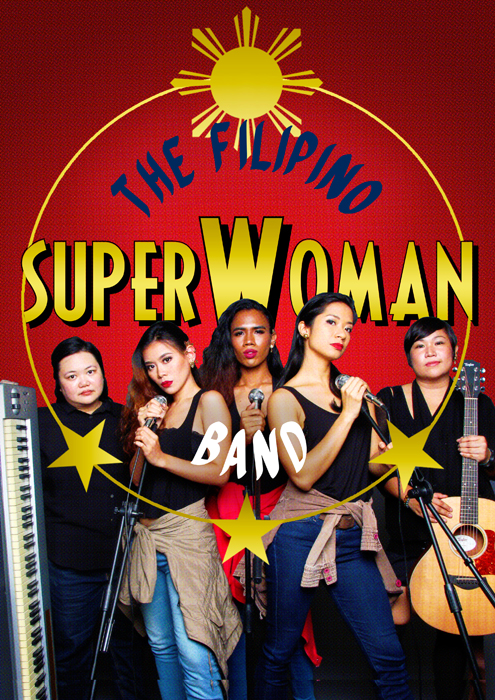

Jocson has recently moved into more experimental territory with the creation of the all-female musical ensemble The Filipino Superwoman Band (2019). Formed in Manila, and comprising Franchesca Casauay, Bunny Cadag, Cath Go and Teresa Barrozo, the band was created in response to the phenomenon of the ‘Overseas Filipino Musician’ (OFM) who performs cover versions of Western songs on cruise boats and in clubs, bars and hotels. Using sound to consider the vulnerability of this migrant labour and hybridised cultural identity, the band problematises the Philippine government’s description of OFWs as Ang mga Bagong Bayani (‘our modern-day heroes’) in much the same way that Princess Studies challenged the princess fantasy. The effect is to highlight the tension inherent in the official celebration of these workers’ contributions to the national economy and the high personal and social cost of their displacement.

In the Princess Studies and The Filipino Superwoman Band, the body – both individual and collective – plays out this tension. But instead of reducing the complex power relations at play in a globalised world of commodified entertainment, cultural exchange and transnational movements, these actions reproduce and remind us of the essentially fluid nature of desire, resistance and embodiment.

The Hugo Boss Art Asia Award 2019, featuring Hao Jingban, Hsu Che-Yu, Eisa Jocson and Thao-Nguyên Phan, is on show at the Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, through 5 January

Stephen Wilson curated Transpersonal, instructions (2018) at the Vargas Museum, Manila

From the Winter 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia