Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the 2 October, 1965 issue of The Arts Review (as ArtReview was then called). The interview took place ahead of Krasner’s first European institutional show at the Whitechapel Gallery that same year. Her retrospective at the Barbican Gallery, London, Living Colour, is her first show in Europe since then, and runs through 1 September 2019

Born in Brooklyn just before World War I, Lee Krasner’s family came from a small village near Odessa. Art was not a factor of her childhood environment, and it was only when she had to make a ‘career preference’ at High School that she became involved in it. In 1927 she attended the Woman’s Art School of Cooper Union, and later spent three years at the National Academy of Design under Jean Kroll. At this time Krasner supported herself by working in nightclubs as a hostess, and later attended evening courses at the City College of New York. Becoming engaged in the W.P.A. Federal Arts Project, she and Harold Rosenberg became assistants to the muralist Max Spivak. During the late thirties she studied with Hans Hoffman and met Clement Greenberg. Through her participation in the McMillen Gallery exhibition in 1941 she met Jackson Pollock. During the next three years she devoted herself to him and exhibited occasionally only in large group shows, principally with the American Abstract Artists. She became married in the fall of 1945 and the Pollocks moved to East Hampton. Her first solo show was held at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951, and her second at the Stable Gallery 1955. In 1956 she made her first visit to Europe, the trip being tragically cut short by Pollock’s death in a motor car accident. She exhibited again at Martha Jackson Gallery in 1958 and was subsequently commissioned to execute mosaic murals in an office building in Broadway. Sigma Gallery mounted a large retrospective exhibition in 1959, and in 1960 and 1962 she had solo shows at Howard Wise Gallery.

***

“It was the artist John Graham, who was well-known before the war who arranged what was for me a key exhibit,” she said. “It was to be at the McMillen Gallery in New York, and I was invited to participate. I was told that this show would contain examples of work by a group of Ecole de Paris artists who were quite clearly, as you will understand, very important at the time. Here was this invitation out of the blue to show alongside of Picasso, Matisse and who knows else. There were to be three young American painters. Myself, de Kooning, whom I well knew, and an unfamiliar name, Jackson Pollock. I thought I knew everyone painting in any sort of modem or abstract manner in New York; but who, I asked myself, was this Pollock? I had to go and see.”

“Who, I asked myself, was this Pollock? I had to go and see”

It is just in such inconsequential ways that chance provides us all with unexpected turning points, wrenches a life into a new track. Before that moment Lee Krasner was a young and very talented painter and well-known among the avant-garde circles of the time. From the time of that climactic meeting in 1941 she was to be overshadowed by the enormous figure of Pollock. And for many years since his death there has been a tendency to regard her simply as ‘Jackson Pollock’s widow’. It is only just now that her very real talents are being recognised, and the large exhibition currently mounted at the Whitechapel Gallery can give us an opportunity to see her real stature.

When I talked to her we were sitting in one of those curiously grotesque rooms of the Ritz. Many people take on a certain skin-colouring, as it were, from their surroundings. But not Krasner. Firm and four-square her enthusiasm glowed in these shabby yet expensive surroundings. There is at the Whitechapel an early self-portrait. She depicts herself standing at an easel in the open air, glancing at the spectator. B. H. Friedman, writing of this painting, says, “It is all there in her face; the receding intelligent blue-grey eyes, the full sensuous mouth between proud prominent nose and jaw, the luxurious red hair, the independence of the figure from its environment – a dozen aspects of emotion and intelligence, pride and vulnerability, all there if not as yet fully resolved.” Now, thirty years later, the face contains the same characteristics, though now resolved by experience and achievement. It has the same openness, the face of a person who strives to live by an act of will, not that of one who merely allows incidents and occurrences to impinge upon her.

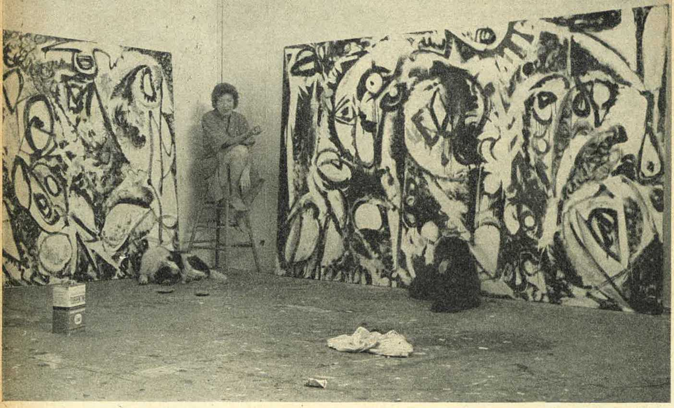

Her paintings reveal this struggle to open out to experience. Her work has not been a steady development along one line, but operates at a deeper psychological level, mirroring her interior life. It appears to have developed into a sort of cycle, and follows a curious pattern. First the pictures are small and dense, right, somewhat closed. They have a feeling of great weight, clearly they have a difficult birth. The paint is thick, layered, built up, image obscuring image. Then over a period of years they loosen, they open up, the paint becomes thin, the images relax, the colour sweetens. Then suddenly there is a shift, a change in style, new referents; but the image is again obscured in thick dense painting. And the process recurs. The paint loosening, the small tight canvases growing into the large open sweeping paintings that terminate the cycle.

Reality, for Krasner, appears to be predominately an inner one… In this way the images are not so much created but released from the very deep levels of the imagination

An image in the sense of figuration is somehow always there, seeming somehow to be trapped in the very paint. “I always work with an image. It’s very clear. Don’t they see that?” Yet she is aware of the cyclic process, the progressive unblocking. Speaking of the paintings she calls ‘hieroglyphs’, she says. “There is a slow build up of pigment. Like hunks of marble. I feel I can’t get the image through.” From these to the vast spontaneous canvases of recent years, however, one can clearly see overriding the periodic cycles the larger cycle of growth. The increase in stature as a person as well as a painter, whose interior life can be imagined as a large river broadening out, being filled and widened by the innumerable tributaries of experience and environment. “The value of this show to me”, she says “is to see the cycle in my paintings”. And these are the words of a person for whom painting is not a career, not a method of assuming masks, of gaining approval, but is an actual process of being, interwoven with the deepest recesses of herself.

This exhibition gives us a chance to see, as I have explained elsewhere in this issue, the work of a very serious artist whose reputation has been overshadowed by that of her husband. Since she is almost unknown in this country we can approach her paintings without any preconceptions and can only stand in astonishment that such a clearly important painter has been so long neglected. Her painting is firmly in the New York Abstract Expressionist tradition, and can stand on a par with any other painter who explores this mode. Her work differs, however, from de Kooning or from Kline for instance in that her approach to the question of reality is different. For de Kooning concrete objective reality remained constant, though it might be ‘abstracted’, and Kline seems to me to have regarded the actual canvas as the objective reality, the ‘made’ object. Reality, for Krasner, on the other hand appears to be predominately an inner one. Here the act of painting is not merely the freezing or capture of a dynamic force or ‘action’, but is a dialogic process between the painter, and that which is not-painter, the canvas. In this way the images are not so much created but released from the very deep levels of the imagination. Though stylistically not related, the method is similar to that of the painters we associate with the Group Cobra in that painting is truly an extension of the artist’s inner life, it is a continual process of creative analysis.

From the 2 October, 1965 issue of The Arts Review