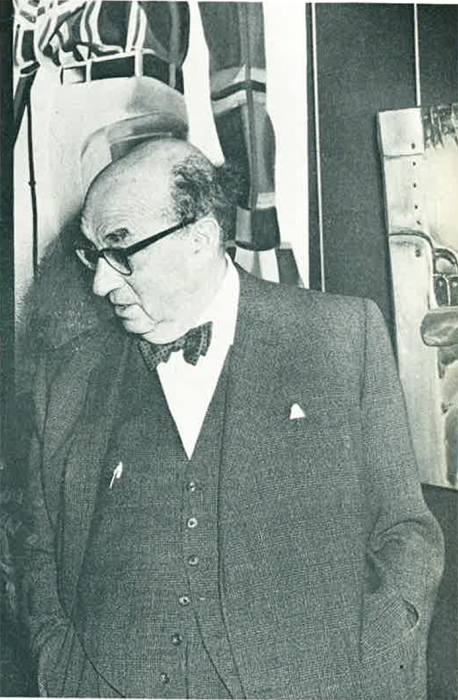

Editor’s note: this article first appeared in Arts Review, 27 September, 1969. It is republished here to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of Arts Review founder Dr Richard Gainsborough.

Dr Richard Gainsborough, Founder of Arts Review, died suddenly on 14th September 1969.

Faced with the calm majesty of death, words suddenly shrink in all their dumb insignificance – our words, debased and dulled by daily misuse. But if we are to pay a true tribute to the memory of Dr Richard Gainsborough, they must shake off all professional proficiency and soar in stern sincerity: nothing but the unadorned truth could do justice to this man of truth.

But words may fail us precisely when we try not to fail him. They may soil with routine rust the purity of the feelings that flood us: respect for his integrity, admiration for his unselfishness, gratitude for his generosity. They may make the pure seem pompous and the true – trite. But we have nothing but these words to repay him for his deeds: a devaluated currency that will leave us for ever in his debt.

And because I owe him more than most, I fear that I may be doing less to honour his memory: private emotions drown the public eulogy. But even they mirror the vocation of Dr Gainsborough: to help and to heal. He helped me to find new bearings in a new land, he healed the loneliness that was crippling my mind. With patient kindness he guided my first steps on my way to a new life. It is hard to write about his last steps on his way to eternity.

I was not the only one to benefit from his far-sighted generosity: many who have gone much higher up in the art world began their ascent leaning on his unselfish understanding: yesterday’s obscure contributors to Art News and Review (as the paper was then called) are today’s museum rulers and law-giving critics. But Dr Gainsborough never resented their desertion. In a way he even welcomed it: his calling was to serve, not to exploit. And he served art with dogged devotion – not on official councils or select committees where much is done for few and nothing for many. He served it where service is most needed: in the muddled mass of striving and starving artists, unknown but not untalented, unsold but not unworthy. With quiet confidence he achieved single-handed a minor social revolution: he broke through the privileges reserved to a handful of handpicked exhibitors and opened the press to all artists. Mayfair and Camberwell became at last equal. The only inequality which Dr Gainsborough ever accepted was the inequality of talent.

This unspoken moral code forged the strongest link between him and those who chose to stay on his side, because it meant to stay on the side of unassuming dignity and inconspicuous independence. Not that he ever posed as an art-prophet eager for worshipping disciples. On the contrary: he did all he could to conceal his rigorous rectitude, to hide the stubborn sparkle of idealism which always shone through the thin veil of ostensible business talks about lucrative publishing projects that usually came to nothing. What bore a rich harvest instead was his unheralded belief that artists are both fathers and children of art and that to serve living artists is to preserve the life of art. Unlike other editors haunted by arrogant conceit, Dr Gainsborough never aspired to divert the course of art: wisely, he surveyed its flow. But he watched relentlessly for all dangers of pollution. The paper he founded was never a dike, always a sentinel. Because he began it at an age when people only end, this paper was born mature – for, unwittingly and unobtrusively, by silent impact rather than by explicit order, he moulded it in his own image: egalitarian but not indiscriminating, open- minded but not unprincipled, tolerant but not indifferent, generous but not condoning, adventurous but not absurd. And now that he has taken his last leave of absence, the paper remains to embody his perennial presence in the lives of those who have become what they are today only because Dr Richard Gainsborough was what few have ever been: a man born to give.

Published in the 27 September, 1969 issue of Arts Review