At the Whitechapel Art Gallery it is again manifesto time. Bursting with brave intelligence, a vast show sets forth to ‘oppose the specaiisation of the arts.’ It proposes to do so by imposing a highly specialised aesthetic theory which may or may not be more than the raw material of the time honoured Experimental Psychology. It is all done with compelling good faith, youthful assurance and provocative intolerance. But then crusaders have never been open minded. Their strength has always resided in their fascination by one belief that they manage somehow to invest with the regalia of the One and Only Truth. And it is to this gush of fighting spirit in the stale air cf conformism that we must pay our tribute, even if we are obviously too uneducated and too old fashioned to grasp the foundations of the Cause.

We must also praise without reservation the intention to extract from life, and to replunge into life, a new category of forms. That these forms will appear arbitrary to those who measure life with the yardsticks of kitchen sinks and espresso bars is only to be expected. Any attempt to rejuvenate the impact of new forms on our daily experiences is bound to be a struggle on the double front of conventional “realism” and equally conventional “modernism.” The exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery tries to fight this double battle. If it occasionally fails, it is because the aim of the collaboration between sculptors and architects fails precisely to “communicate” with life and moves only along the “channels” of gratuity that lead back to Dada and from there straight into the formalist wilderness where man and art shall never meet.

This must not be mistaken for a plea for some kind of outdated humanism. It is merely the expression of the necessity of a direct and sincere link between the formal evolution of art and the evolution of life. And it is what seems to me a misconception of the nature of this link that throws off balance this otherwise well-intentioned exhibition.

It is true, and it is worth stressing again and again, that the perception of sculptural and architectonic forms should follow the same psycho-physiological “channels.” It is equally true that all forms are not only a matter of vision, but also a matter of thought: the Florentines called five centuries ago “cosa pensata” what the present day theory chooses to term “encoding” and “decoding.” It is equally true that architects, lost in their calculations, chained by their clients, all too often seem inclined (or forced) to relegate in the background the visual coherence of their work, which we perceive according to the same rules that we apply to our acceptance of sculpture. But to bring this visual concern into the foreground does not mean to assimilate sculpture to architecture, as this exhibition seems to do, mistaking perception (which is indeed the same in both cases) with rational evaluation (which is bound to be different).

The exhibits are hybrid forms, too devoid of inner strength to be authentic sculpture and too aimless to be architectural concepts

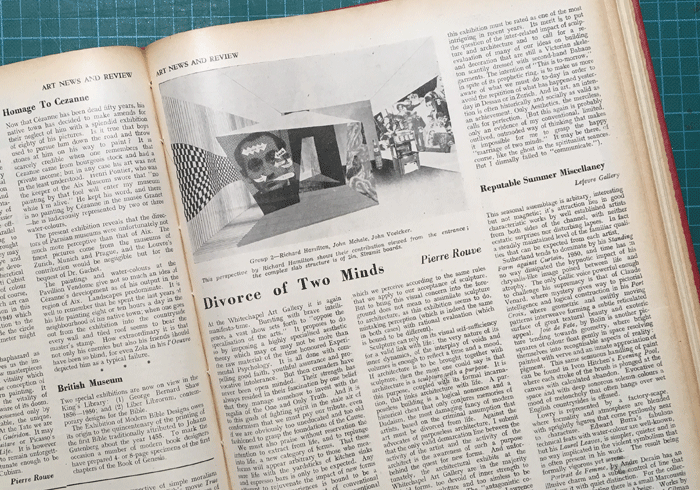

Sculpture can rely on its visual self-sufficiency for a valid link with life: the very nature of its inner dynamics, of the interplay of voids and volumes is enough to reflect a time and a mood. If architecture is to be brought together with sculpture, then the most one could say is that architecture is a sculpture .with a purpose. It is this purpose, coupled with its formal incarnation, that links architecture with life. A purposeless building is a logical nonsense and a historical cheat that only conjures memories of Dadaism, the most damaging fancy of modern artists, based on the criminal assumption that art must be divorced from life. Against the advocates of purposeless architecture, I submit that the only valid demarcation line between the activity of the artist and the activity of the architect is the awareness of such a purpose behind the quest for new forms. And unfortunately, the architectural exhibits at the Whitechapel Art Gallery are in the majority hybrid forms, too devoid of inner strength to be authentic sculpture and too aimless to be architectural concepts. The “antagonistic cooperation” so intelligently sensed by Lawrence Alloway has degenerated into an almost general unconditional surrender of the architects to their formalistic fancies. There are perhaps a few exceptions in the teams including Cosby, Voel- ker, Carter and Wilson: there the architectural thought has not been diverted by arbitrary juggling with peaceful structural elements forced much against their will to look like something different from a “wall.” A similar strain on naturally modest imaginations has led others into false sophistication, swinging from brie a brae “with a message” to mere screens with ludicrous decoration.

In this whirlwind, the sculptors emerge triumphant, though much care has been taken to make impossible the isolated contemplation of their works. But what had been conceived as a continuous flow of “communication” between exhibits and spectators has been broken in a machine gun succession of isolated messages, that even the most advanced decoding machine would be unable to cope with—let alone the sight and the brain of the uninitiated.

But in spite of this partial failure to produce a balanced and entirely convincing compound, this exhibition must be rated as one of the most intriguing in recent years. Its merit is to put the question of the inter-related impact of sculpture and architecture and to call for a re- evaluation of many of our ideas on building and decoration that are still a Victorian skeleton scantily dressed with second-hand Bauhaus garments. The intention of This Is Tomorrow, in spite of its prophetic ring, is to make us more aware of what we must do to-day in order to avoid the repetition of what has happened yesterday in Dessau or in Zurich. And in art, an intention is often historically and socially as valid as an achievement. Only Aesthetics, the merciless, calls for perfection. (But this again is probably only an evidence of my conventional, limited, outlived, outmoded way of thinking that makes it impossible for me to grasp the happy “marriage of two minds.” It may be there, of course, like the ghost in the spiritualist seances. But I dismally failed to “communicate.”).

This article was first published in the 18 August 1956 issue of ArtReview, then styled Art News and Review