I wonder what Virginia Woolf would have thought of her plate, a great green-yellow and pink pod burst open – like D.H. Lawrence’s Figs! The pod sits glistening, inviting, on a pale custard yellow runner. Virginia loathed custard. Especially with the prunes that were women’s fare at her college table at Cambridge. But Judy Chicago rides roughshod over such delicate palates. Her plates had to rise up (oh dear!) to thrust themselves forward – to symbolise women’s growing struggle for liberation. I have no argument with this but as she also demands that the work be seen as art then we have to see The Dinner Party not only in terms of its ideology but in the full context of art, feminism and politics. And I am not sure that The Dinner Party is a truly feminist work.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1939, Judy Chicago began the project in 1974 after years of working politically as a feminist artist, difficult years which she documents in her autobiography Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist, published in 1975. The Dinner Party was conceived by her as ‘a large-scale work of art symbolizing the achievements of women in Western civilization’. It took five years to complete with the help of almost four hundred people working under Chicago’s direction. It received not only Federal funding but contributions from thousands of individuals across America.

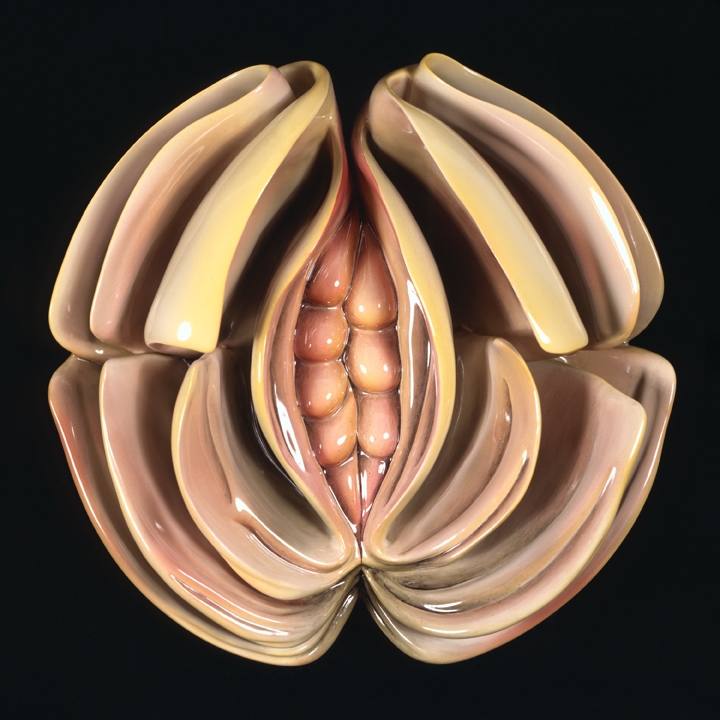

The Dinner Party is an open triangular table, 46 1/2 feet each side, covered with white cloths laid with thirty nine place settings, thirteen each wing, representing ironically both the number of guests at the Last Supper and the number of members in a witches’ coven. Each place is laid with an elaborately painted plate, lustred ceramic flatware, a chalice and a gold edged napkin resting on an embroidered runner. All is of a scale and splendour which emphasises the heroic achievements of the woman/goddess represented. The great table stands on The Heritage Floor comprising 2300 handcast porcelain tiles inscribed in gold lustre with the names of a further 999 women of achievement.

The overwhelming scale of the piece in its dark chamber fires one’s pagan imagination. We are witnesses to some ancient, supernatural feast, whose meaning has in part died with the bodies of the absent guests. While we feel comfortable contemplating the plates for the Goddess Kali or the Warrior Queen, Boadicea, we feel a bit disconcerted by the frilly pink knickers plate for Emily Dickinson, American poet who died in 1886. It is the later plates which seem most pagan, alien almost in their grotesque sci-fi barbarism. While the whole work celebrates the skill of women’s needlework, weaving, china painting – the gross vulgarity of Judy Chicago’s designs seems to me to undermine the brilliant art of women’s past achievement. The fine delicacy of Elizabethan beadwork and lace is not well served by the garish purple plate of Elizabeth I set on its grisly doily. Faced with these monsters, I could not help thinking of the restraint of English Eighteenth century porcelain, designed and painted in most part by anonymous women and children. The repeated use of genital imagery (each plate is a variation on the image of the vulva), however disguised, is also problematic. It is coyly referred to in the exhibition booklet as ‘the feminine principle’ and left at that. But we cannot ignore Lawrence:

“What then, good Lord! cry the women.

We have kept our secret long enough.

We are ripe fig. Let us burst into affirmation.

They forget, ripe figs won’t keep… ”

Surely the iconography of the vulva in art and literature is so crucial to the work’s message that some discussion is essential? This omission seems to me to underline a paradox in the whole work.

The Dinner Party, its conception and its creation, aims to celebrate femineity: female wisdom, female strengths and female qualities. Yet the work is outrageously male in many respects; it is monumental; its surface, its feel is hard and unyielding. In spite of the democratic tribute to its producers the razz-a-ma-tazz of the work’s installation celebrates the zealous energy, talents and commitment of its creator, the artist Judy Chicago, Boudicca of feminist artists. In some senses I felt more moved by the anonymous little quilts of the Honour Quilt donated by women the world over. This though is also Judy Chicago’s creation. And, in spite of my reservations about The Dinner Party, I look forward to The Birth Project, which celebrates a subject rarely seen in western art, creation mythology and childbirth. I hope DieHard Productions, who showed great tenacity and ingenuity in bringing The Dinner Party to Britain, will find more support from the art establishment. It is testament to the importance of their work for women artists that The Dinner Party had to be housed in a marginal site behind King’s Cross – secured through the goodwill of a private landlord and the G.L.C. (to May 26. The installation was previously shown, and noticed in Arts Review, at the 1984 Edinburgh Festival)

Judy Chicago is best known for The Dinner Party, a sprawling installation shown first in 1979 at the San Francisco Museum of Art. This, together with projects such as Womanhouse (1972, with Miriam Schapiro) and The Birth Project (1980–85), are cornerstones of her reputation as a pioneering feminist artist

Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton is an art historian, curator, writer and editor who, following a decade or so as a critic for Arts Review, relaunched Artscribe International in 1992. She has held executive positions at Arts Council England (1993–2006), AiCA UK (2009–18) and AiCA International (2015–18)

From the March 1985 issue of ArtReview (then titled Arts Review). This article was republished in the 70th anniversary issue of ArtReview, March 2019