The artist has fostered an intense, thoughtful practice structured on the process of paying attention to the abundant yet elusive minutiae of daily life

This profile – first published in the September 2016 issue of ArtReview – is republished here to coincide with Ignasi Aballí’s Spanish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale.

Hojas (Leaves) (1978) consists of hundreds of dried tree-leaves cut into rectilinear shapes and arranged into a loose grid pressed between two framed sheets of glass. It is an impressive object, the sort of thing that can stop museumgoers in their tracks: an earth-toned, semidiaphanous, textilelike study of colour and texture. That its author, fifty-eight-year-old Ignasi Aballí, had never exhibited this work before last year’s sprawling survey exhibition at Madrid’s Reina Sofía museum, where it could be seen tucked away in a corner, is rather surprising, for Hojas presages to a remarkable degree the core concerns around which the Catalan artist’s oeuvre would develop over the following decades: the search for ways by which to bring the impulses of a painter to the image-making process without recourse to the act of painting or even to paint itself; the incorporation of unconventional materials imported directly from the ‘real’ world into the art object; and a skilful harnessing of the poetics of transience, decay and ephemerality. Above all, Hojas announced what would become an intensely thoughtful artmaking practice structured on the process of paying attention to the abundant yet elusive minutiae of daily life – or in Aballí’s words, to the “murmur of the everyday”.

In developing this practice, Aballí has employed an eclectic range of materials, including dust (“dust is a very complex substance – it contains everything,” says Aballí), sunlight, typewriter correction fluid, newspaper clippings, corrosion, lead type from obsolete printers’ shops, scuff marks, books, found photographs and numerous other objects. His range of media is similarly broad (and, understandably, somewhat resistant to rigorous classification): Aballí’s preferred formats include photography, video, installation, drawing, language-based works on a variety of support structures and even paintings (with or without what might be called ‘paint’). And yet despite its committedly freewheeling, ecumenical approach, Aballí’s work does not slip into the trap of calling attention to its own eclecticism. To the contrary, at its best it operates, regardless of specific medium or format, on multiple levels of discourse – perhaps it will offer a conceptually oriented mining of the fruitful tensions among image, object and language, or a shrewd handling of the dialectic of intentionality in the artmaking process, or an oblique and unstrident institutional critique, or any combination of the above – while remaining almost shockingly simple in execution. As a result, it comes off as clear rather than clever, wise rather than overwrought.

For instance, during the 1990s Aballí made a number of works entitled Luz (Light) that sprang from his observation of the way the Mediterranean sunlight in his studio in Barcelona weathered anything and everything exposed to it. In response, Aballí propped cardboard sheets on the wall opposite the studio’s high windows. Over the course of months the light slanting through the windows discoloured the cardboard into a floating minimalist grid of surprisingly precise rectangles: the yellowed shadows of the window’s panes thus become a painterly yet literal manifestation of all that, in fact, remains of the day. In Papel Moneda (Paper Money) (2010), Aballí obtained banknotes that had been removed from circulation and shredded by the Bank of Spain. Aballí filled framed, vitrinelike cases with the valueless shreds so that they presented textured, near-monochrome studies – literally the ‘colour of money’ – while also invoking the fraught, charged and yet alarmingly tenuous symbolism underlying all legal tender. Aballí’s scrutiny of the negligible and overlooked has even extended to the invisible, as in his languagebased works, often installed in exhibition spaces on windowpanes or Plexiglas sheets, that straightforwardly enumerate the gaseous components of the common and all-embracing substance we refer to so easily as ‘air’.

“Ignasi begins from the core idea of reduction: trying to find a single, humble element from the greater field of signifiers floating around out there, and presenting that element in a way that it stands for everything associated with it,” comments Dan Cameron, an independent curator who has included Aballí in various groups shows over the past 20 years. “When he made his first light pieces in the 1990s, he was pointing to the particular light that entered the space and illuminated the works, but also to the central role light plays in a painting.”

“In the 1990s there was a moment when things were very open, when artists in different places were able to take the practices of conceptual art and create new ways of making, especially of image-making,” says João Fernandes, the deputy director of the Reina Sofía, who curated Aballí’s retrospective at the museum. “Ignasi, coming out of Barcelona, belonged to that generation and has dealt with all those concerns. But he’s also developed a very personal vocabulary of materials and objects, a very personal process that uses time and daily life, a very personal economy of the image based on visibility and invisibility.”

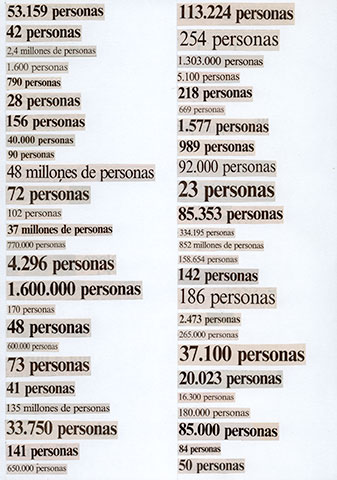

One of the characteristics that has distinguished Aballí’s work over the course of his career has been its capacity to incorporate stylistic shifts that not only accommodate but renew the perduring base concerns; in other words, Aballí’s work is not unpredictable, but it is often surprising. For instance, Páginas (Pages) (2013) presents vitrines full of neat rows of pages torn from ageing books in installations that distinctly recall the yellowed patches of sunlight in the early Luz series, and yet at the same time speak to a distinctly different set of issues. Nonetheless, Aballí is still probably best known (particularly outside of Spain) for the series of works generally titled as Listados (Lists) that he created between 1998 and 2015. In these works Aballí clipped headlines each day from the Spanish newspaper El País, then grouped the isolated phrases based on their content: for instance death tolls, forms of currency, ‘-isms’, professions, nationalities, monetary quantities or units of temporal measure (just to mention a few). One Listado refers to kinds of drugs; another, to the numbers of missing people; and another simply to numbers of years, ranging from one to 14 billion. The decontextualised headlines are arranged into columns, unembellished and unadorned, and then scanned, enlarged and printed on photographic paper; the resulting artwork sometimes builds into a kind of modular, verbless poetry, while at other times induces a jolting glimpse of daily reality, a fast-track psychic bridge between the word and the world.

“Ignasi is deeply interested in mortality, and to the ways our constant exposure to waves of information and images numbs us to the realities behind them,” says Cameron, who is including a version of Listados in the 13th Cuenca Biennial, opening in late October in Ecuador. “The Listados are a good example of how great tragedies, broad sociocultural disruptions and mass phenomena are reduced to objectified figures: 50 people, 1,000 people, 50,000 people, etc. Although one death seems less than 50,000 deaths, it is simply the particularisation of a category that humans are naturally fascinated by: how other humans die, where and in what numbers.”

“I try to avoid the material, handmade quality of collage, to take a work that is so clearly rooted in text and shift it into the realm of the image,” Aballí says of his Listados. “And as photographic images, I wanted to construct them so that they are images of reality: a photo about death; a photo about money; a photo about time.”

While Aballí cites visual artists such as On Kawara, Michael Asher, Christopher Williams and Christopher Wool (and, more fundamentally, Duchamp) as references for his own practice, he also cites filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and Robert Bresson, and writers such as Samuel Beckett, Thomas Bernhard and, above all, Georges Perec. Indeed, Aballí’s proclaimed allegiance to the “murmur of the everyday” clearly echoes Perec’s quest for the ‘infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual’. And in fact a key work in the arc of Aballí’s career – arguably the project that first consolidated his position in the Spanish artworld, where he is revered – was Desapariciones (Disappearances) (2002), a series of fictional film posters and a related video based on Perec’s film projects and named after Perec’s novel La Disparition (A Void, 1969).

In writing La Disparition, Perec imposed on himself the ‘lipogrammatic’ constraint of completing an entire novel without ever using the letter ‘e’ (the most common letter in the French language). Thus Perec’s tour de force is built around an absence, while in Aballí’s Desapariciones, absence also acquires generative force, for the majority of the films that the ‘posters’ purportedly announce were never made and are thus absent from the existing world of celluloid. Aballí’s meticulously crafted images are visually plausible and credible, and yet they are fabrications of his own devising, fictions about unrealised fictions, hybrids of existence and nonexistence; and yet they themselves are incontrovertibly (and rather delightfully) real. Ultimately, Desapariciones is as much in keeping with the ingenuity of Perec’s writing as it is with Aballí’s own focus on the interplay between reality and fiction, between written language and visual art, and between appearance and disappearance.

Aballí’s studio, which he has occupied for nearly 30 years (he moved in soon after completing his studies at the University of Barcelona under the mentorship of Catalan painter and printmaker Joan Hernández Pijuan), is in the feisty, gritty Raval neighbourhood of central Barcelona. The studio itself lies deep within a nineteenth-century building that was originally a piano factory and still bears the signs of its industrial origin: a shadowy, cavernous, large-stone entrance; wide-slatted and heavily worn wooden stairs and floors; high ceilings with numerous exposed, weight-bearing ceiling beams; vast windows that don’t quite shut properly and cannot be fully cleaned; and a consequent propensity for dust. The space is cluttered but orderly – for instance, Aballí archives his trove of clipped newspaper headlines in old wooden cigar boxes, perched precariously one atop another. Absent is the clean, meticulous, minimalist formal aesthetic characteristic of much of the work. And yet on closer inspection the studio, with its age, its accumulations and its draughtiness, reveals itself to be an entirely understandable abode for the development of Aballí’s particular kind of minimalist, noninterventionist ethic; it is a place in which other processes – of light’s colouration and discolouration, of the accumulation of dust, and above all of the passage of time – might be allowed to run their own murmuring course, at their own pace and in their own way, whether or not at the service of art. Which, of course, they will do anyway.

This article was first published in the September 2016 issue of ArtReview.