The architecture of death is evoked in the American artist’s latest exhibition, which hints at violent nihilism without ever fully revealing itself

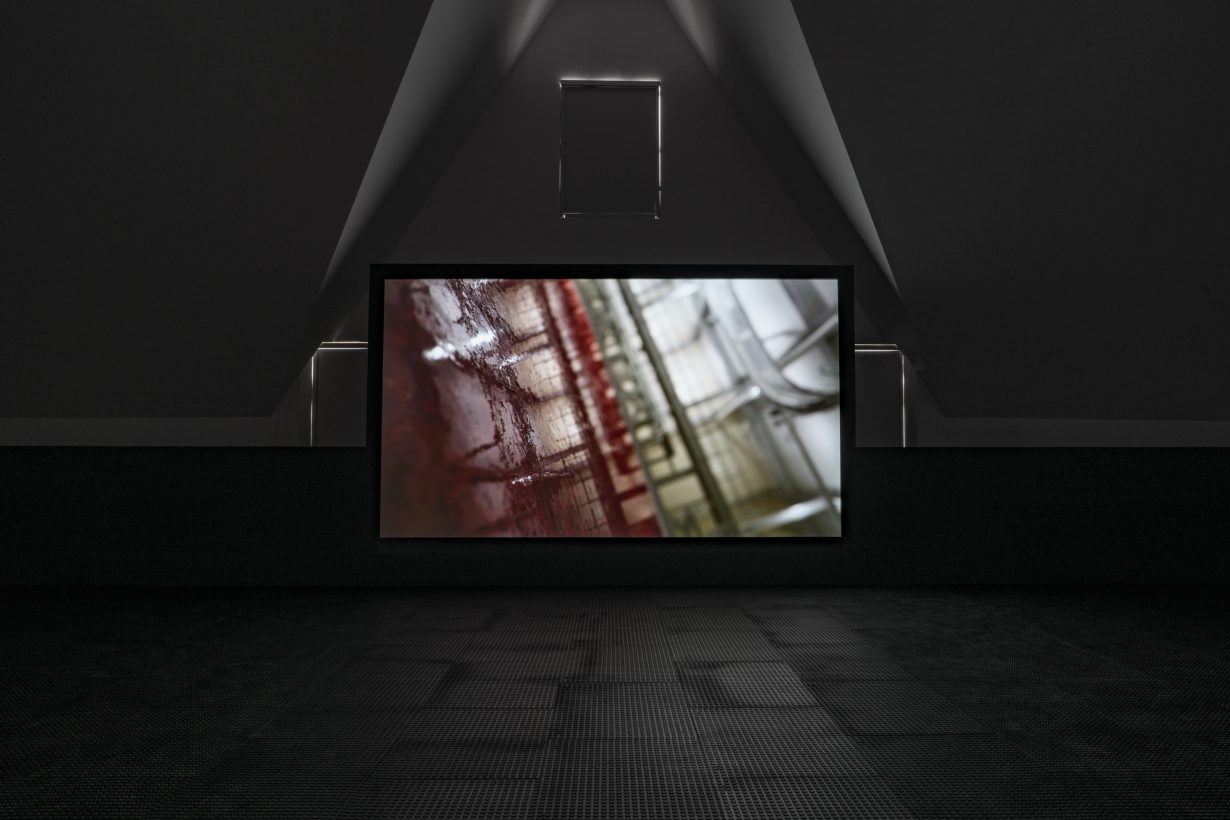

Artist and writer Aria Dean’s latest exhibition builds upon her critical exploration of the ontology of Blackness across sculpture, video and installation; the present film, Abattoir, U.S.A.!, works to imagine the constitution of a subject position through a combination of abstract and representational means. The gallery, entered through two flimsy swinging doors equipped with circular windows and impact plates, features a rectangular perimeter of six-foot-high walls enclosing the viewing area for Dean’s film projected on a screen. Button-patterned rubber tiles cover the floor. Their scent is strong. Sound ricochets around the room from the eight-channel audio system. These minimal interventions enhance the bodily sensation of occupying space. But the video, produced entirely with 3D animation software, blunts this spatial sensitivity. The film travels through a pastiche of industrial architecture with an aseptic and unfeeling gaze, one that distances rather than immerses the viewer.

Resembling online videos demonstrating modern-day livestock slaughter methods, the first-person viewpoint progresses through interiors in which bovine subjects might be held, herded, stunned and exsanguinated. There are no butchers or beasts in Dean’s video; instead, there is only an implied subject position imparted through the pans and shifts in focus of a virtual camera.

So what’s going on? It’s tame for a film rehearsing slaughter, but consistent with a contemporary disposition that is coolly acclimated to mass death. There is no onscreen violence, but certain visuals imply that death or dying is happening. In the middle of the film, after the camera enters a metal guillotine-like apparatus in which cattle might be stunned, an abstract sequence suggests a loss of consciousness. Black-and-yellow flickers evoke the undulation of colour visible when one’s eyes are closed. The flashing stops and opens to a canted angle of a bloody floor and an out-of-focus room – what one might see after falling to the ground.

This first-person point of view, oddly, reinforces the absence of a subject, staging a negative ontological condition of not-being and not-becoming. No limbs – animal or human – enter the camera’s view, nor is there any sound to suggest activity beyond the movement of the camera. Only the presence of architecture is registered, whether in shadows captured during shifting lighting conditions or in reflections seen in the glossy, blood-soaked floor. Death is positioned as a nonrepresentational condition, figured by the lack of life. The viewer cannot know what lens they are seeing through and as a result has no framework for empathy.

The deep lack of meaning at the heart of Dean’s video contrasts sharply with the discursive scaffold offscreen. Dean’s research originated from an overlap she identified in the writings of French poststructuralist Georges Bataille and American Afropessimist Frank B. Wilderson, who both briefly explored the topic of slaughterhouse. The exhibition text gestures to Dean’s research on modernism’s inheritance of the slaughterhouse as a generic, self-effacing nontypology that aligned with twentieth-century attitudes towards design – and more baldly, death. Dean presumably views the coalescence of design and death, here both stripped of ornament and ritual, as potent concepts for a philosophical project in which she seeks out objects that dodge or subvert representation to express the continued subjugation of the Black subject position. For Wilderson, this is the status quo – the irreconcilable antagonism between Blackness and everything else is inescapable. It’s not a defeatist position, but a vehemently defensive one that rejects any dissenting view. Dean’s film concurs with this position, putting forth a nonoppositional gaze, in which presence is constituted through absence, a condition bell hooks identified in earlier modes of cinema that enacts the subordination of Black female spectators.

This critical architecture crowds the self-sufficient video installation, which perhaps needs no explanation. If Dean’s ultimate goal is to embody nihilism, then why sanitise the film with discourse? If we look to the other pole of Dean’s intellectual project, Bataille’s abyss is not a place of mere contempt or boredom, but a site where incompleteness and incoherence generate a delirious kind of meaning that works against itself. Dean has dug an exquisite hole, but it could be a tad dirtier.

Abattoir, U.S.A.! at The Renaissance Society, Chicago, through 16 April