The Dutch-Filipino artist traces evidence of the current global climate crisis through the changing life of islanders in the Visayan Sea

As is the case elsewhere across the globe, the dominant forces of the twentieth and twentieth-first century – neoliberal and autocratic politics – have brought environmental destruction to the Philippines. Here, environmentalists date much of this destruction to the second half of the twentieth century, when President Ferdinand Marcos’s modernisation policies, such as the 1967 Investment Incentives Act, aggressively encouraged foreign investment that broadly stimulated and facilitated the abuse of natural resources. A 2002 study titled ‘Philippine Biodiversity Conservation Priorities’ (copublished by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Conservation International, the University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies, and the Foundation for the Philippine Environment) estimates that only 7 percent of the country’s original, precolonial forest cover remains.

These ecologically reckless policies, in tandem with the country’s rapid population growth and general vulnerability to augmented natural disasters caused by climate change, are now having serious financial and social consequences: a 2013 article by Time magazine titled ‘The Typhoon’s Toll’ estimated that that year’s Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) cost the Philippines approximately US$14 billion; the 2016 El Niño caused significant declines in fishing as well as in sugarcane and rice production, heavily impacting the rural poor in particular, who largely rely on local agriculture and fisheries for food supply; 50 of the country’s 421 principal rivers have been declared biologically dead. It is worth noting that the government’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources has taken serious steps in reevaluating the Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan and has led initiatives supported by President Rodrigo Duterte to clean Manila Bay and Boracay. Environmentalists have voiced their concerns, however, that these actions are once again economically motivated, as the president is simultaneously pushing an aggressive charter change to the 1987 constitution that would remove restrictions on foreign ownership and control of land, once again making the country’s natural resources susceptible to capitalist abuse.

Born in the Philippines to a Dutch mother and Filipino father, Martha Atienza uses her artistic and ecologically focused practice to reappraise the local traditions in which human subjectivity, society and the environment are intertwined. She splits her time between both countries, making her home in the Philippines on Madridejos, Bantayan Island, in the Visayan Sea, where she grew up. President Marcos granted the island (and over 50 others) protected status as a Wilderness Area in 1981 with Proclamation No 2151, which prevented ‘sale, settlement, exploitation of whatever nature […] subject to existing recognized and valid private rights’. The 109 sq km island has a population of approximately 120,500 people but was devastated by Yolanda. The local government has wanted to prioritise the rebuilding of the island for tourism and economic profit, resulting in the Philippine Congress voting to revoke the island’s Wilderness status in November 2019 (House Bill No 3861). Atienza’s most recent exhibition at Silverlens, Manila, which took place at the end of last year, operated within the context of this uncertainty and was titled Equation of State. In it she prioritised the environmental impact of the revoked status beyond the obvious probes into the Philippines’ economic, political and cultural motivations – a consistent focus of her oeuvre so far, which endeavours to identify, examine and present the environmental crisis as an omnipresent and central force rather than a peripheral concern.

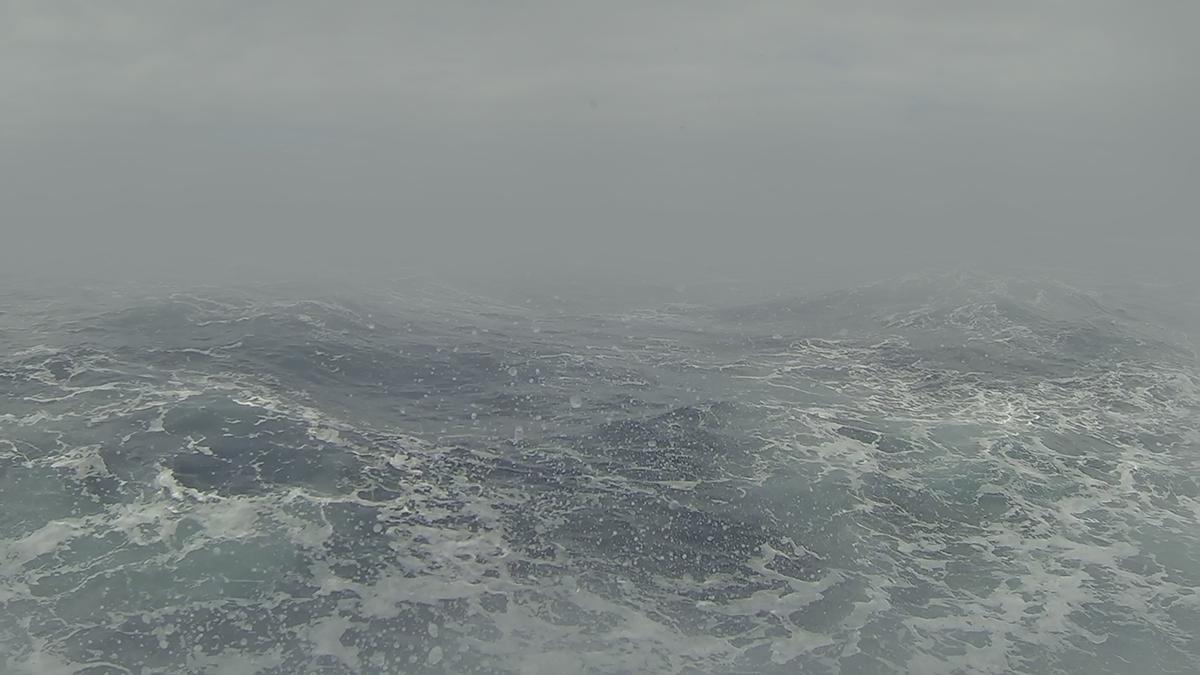

Atienza’s various films, in turn, are interconnected as they document and interact with the changing nature of Bantayan Island and those who inhabit it. In works such as Anito 1 (2011–15) and 2 (2017), which were shot over several years, she follows tangible existential and cultural shifts of the kind she pointed out in a 2017 CNN article: ‘People are simply hungrier than before, and it shows…,’Atienza is quoted as saying. When it comes to community gatherings and traditional festivals, there are ‘no more crazy, elaborate costumes; no more painted rice sacks. Some people don’t even join [traditional festivals] because they choose to go fishing instead – their families have to eat.’ In her most recent film, Panangatan 11°09’53.3”N 123°42’40.5”E 2019-10-24 Thu 6:42 AM PST 1.29 meters High Tide, 2019-10-12 Sat 10:26 AM PST 1.40 meters High Tide (2019) – in which she documents the state of the islet’s coastal decay at high tide via the effects of rising sea levels on housing – she highlights the contemporaneous consequences of global warming.

For Gilubong Ang Akong Pusod Sa Dagat (My Navel is Buried in the Sea) (2011), Atienza collaborated with the locals of Madridejos, Bantayan Island, as well as Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) in Rotterdam to create a three-channel installation. The 31-minute film oscillates between the lives of locals and OFW as they interact with the sea for their livelihood. There are closeup shots of men layering on worn long-sleeved shirts – unusual when compared to the developed world’s notion of diving gear – and engaging with Visayan voices offscreen: “Put your hat on properly!” one says, as the man quickly fixes his balaclava, “Like a thief,” another voice suggests. The crowd cheers the men on when they finalise their uniforms and pull on oval diving masks complete with makeshift headlamps made from a flashlight and the tyre of a child’s bicycle. Additional scenes show the men jumping into the ocean with tubes in their mouths – they are compressor divers, a dangerous type of fishing profession that borrows its name from the low-pressure air compressor to which the plastic tubes are attached (they are also run through a bottle of Sprite to cleanse the taste).

My Navel… interrupts these local scenes with clips of Filipinos working onboard a cargo ship. In the Philippines, making a livelihood as an OFW is seen as more lucrative than local fishing, in part due to the unprofitability of fishing due to climate change: ‘Imagine,’ Atienza says in the CNN article, ‘before it would take a few hours to catch 40 kilos. Now it takes a whole night to catch a few kilos. And the fish caught are actually too small – they haven’t spawned yet.’ This lifestyle echoes that of others in Southeast Asia who are tied to the changing sea. In a 2016 documentary titled Jago: A Life Underwater, for example, Rohani, an eighty-year-old hunter-diver of the nomadic Bajau people, recounts the transformations that have occurred during his own life, including industrialised trawler fishing, a decline in fish stocks and the death of his only son following a diving accident.

Ultimately, My Navel… was created for and by the people of Madridejos as a collaborative project to instigate a discussion among the local community. The project’s dedicated blog explains, ‘It was important to emphasize on the importance of sharing stories and experiences with one another: families and members of the community’. First and foremost, this film aimed to empower those it portrayed. In a related interview, fisherman Mario Forrosuelo reveals, ‘Our ancestors used to say, “We come from the sea, there is where we start and where we will end. That is our inheritance.”’ Atienza would continue to work with local compressor divers in later series.

She also continued to probe the traditional relationship between the residents of Bantayan Island and their culture in Anito 1, which documents the Ati-Atihan festival that honours Santo Niño, the Infant Jesus of Roman Catholicism. Ati-Atihan, however, means ‘to be like the Aeta’, which are an indigenous group thought to be one of the archipelago’s first inhabitants. Popular religion in the Philippines tends to combine precolonial spirituality with the Catholic canon, with the animist influence being more pronounced in rural areas. Though the definition of anito varies by region – given the oratory tradition of indigenous religion – it generally describes the sentient spirits of both ancestors and nature that communicate with the Supreme Being for intercessions on behalf of the living.

Anito 1 documents the comedic and satirical personalities participants adopt via their costumes, which are often critical of current events: for much of the film, it follows a shirtless man donning a golden and curly wig, dressed as the Santo Niño sculpture he carries as he struts through the streets. Other costumes include world-champion-boxer-turned-politician Manny Pacquiao and a Typhoon Yolanda survivor.

Atienza reprised the project two years later with Anito 2 because she saw a clear difference in the ways that the Madridejos locals celebrated the festival: there were fewer and fewer participants as working came to be prioritised over celebration, and costumes turned less colourful, more sombre. Here we see a man holding a sign that reads, ‘I am a drug lord, do not copy me’ in Visayan as he is escorted by uniformed men holding guns. While Anito 1 and 2 document contemporary events as seen by the Bantayan Island community, the films also make connections to the past, when relationships between man, spirit and nature were integral. Indeed, conservationists and environmentalists have begun to look towards folk beliefs for guidance in protecting nature. Elias Victor, an Ati leader quoted in a BBC article this past July, says, ‘This what our ancestors told us: “It is not just us – humans – who exist in this world. There are also those that are not visible to our eyes… They take care of the source of our food and water. When we eat, we invite them, too.”’

Atienza’s internationally acclaimed work Our Islands 11°16’58.4”N 123°45’07.0”E, which won the prestigious Baloise Art Prize at Art Basel in 2017, coalesces the major subjects of My Navel… and Anito. In this single-channel, 72-minute film, compressor divers in familiar costumes (the Santo Niño, the Typhoon Yolanda survivor, Manny Pacquiao and the drug lord are among those from Anito) execute the Ati-Atihan procession underwater to alienate the viewer and force them to confront the palpable oceanic climate change seen in the seabed of dead coral. The participants first move slowly across the screen from left to right, then disappear behind the camera and circle to appear, once again, on the left side of the screen; each time they pass the lens, the performers accelerate to close the gaps between one another. As these figures move across the barren seabed, the consequences of climate change are undeniable and ubiquitous. Experiencing the soundless Our Islands is almost voyeuristic – you feel like you’re a visitor to an aquarium – marking the separation between passive viewer and active diver. However, what distinguishes this from a demonstration of the typical voyeuristic gaze is the consciously performative nature of the procession. The costumes and animist traditions seen in Our Islands further prompt the question, ‘Who do these islands belong to?’ The passive international viewer, or the participating, local community? In several Filipino languages, ‘our’ is translated into different words that either include or exclude the addressed – in Visayan, kanato and kanamo respectively. Given Atienza’s previous willingness to title her films with local languages, the deliberately vague English ‘our’ leaves the islands’ referential relation ambiguous.

Significant to Atienza’s aesthetic practice is her active social obligation to her community. Rather than passively documenting the people and ecology of Bantayan Island, her social practice helps to augment the full complexities of human subjectivity, society and the environment. As she says, ‘My work is always inspired by the question: can art trigger empowerment and tackle real issues in society?’ On a micro-level, Atienza has prioritised the empowerment of the local communities her art depicts. Para sa Aton (For Us) (2013) – which uses the inclusive ‘us’ – documents the community working together to study bio-intensive farming, rebuild a marine sanctuary and develop sustainable paid opportunities for women. On a wider, macro-level, Atienza has importantly developed an artistic practice rooted in the invigoration and preservation of heterogenous experience that is presented nationally and globally as a form of difference within the mutually inclusive global crisis. ‘Climate change isn’t only happening in the Philippines,’ Atienza has said. ‘It’s a common issue we all have, and we need to talk to each other as neighbours.’