In September 2020, under House Bill 7137, 197 legislators of the Philippine House of Representatives voted to declare 11 September President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Day in the dictator’s home province of Ilocos Norte. The decision came just weeks before the 48th anniversary of Martial Law, imposed on 23 September 1972, prompting many to wonder how Marcos’s reputation had managed to be rehabilitated to such an extent. After all, his autocratic leadership in the period 1965–86 was responsible for thousands of human rights violations – Amnesty International counts over 3,200 extrajudicial deaths, 34,000 cases of torture and 70,000 imprisoned Filipinos. Meanwhile, the Philippine Supreme Court estimates that the Marcos family pocketed $10 billion during their 21-year tenure, most of which now hides in foreign bank accounts and accumulated luxury goods. This recent legislation represents one of many events that continue to baffle both the local and international community, leading to debates as to why this late, corrupt dictator continues to be revered in the very country he tyrannised and mercilessly plundered for over two decades.

It is within this landscape of unexplained wealth and indifference to the plight of the Philippine people that artist Pio Abad has set his ongoing project The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders (2014–). The title derives from the pseudonyms used by Marcos and his wife, Imelda, on their Swiss bank accounts, which Abad then fashions as a grandiose property title used to inflate an object’s significance. Throughout the work’s various iterations, the artist identifies the Marcos family’s former luxury and fine-art possessions and reproduces them, endowing these new objects with a hauntology.

Born in Manila, Abad grew up in the final years of the Marcos era and its aftermath. His parents, both political activists during that time, were incarcerated for their critical dissent of the regime. Abad studied at the University of Philippines in Manila, then left the country in 2004 to pursue a bachelor’s degree in painting and printmaking at Glasgow School of Art. He went on to study at London’s Royal Academy and has lived in the British capital ever since. His socially and politically charged artworks operate within a gamut of material and mediums – textiles, drawing, installation, photography – to awaken historical spectres of greed, neocolonialism and neoliberal negligence.

In 1965 Marcos won his first presidential term with a populist campaign that touted him as a decorated Second World War hero. Imelda, a former beauty queen, also proved paramount to his bid with her charm and sharp political instincts. The pair would sing duets during political rallies, foreshadowing the performative and saccharine, conjugal dictatorship to come. During his first term, Marcos initiated and supported vast infrastructure projects funded by foreign investment, which made him popular enough to be the only Philippine president elected to a second term (critics would argue that vote-buying and electoral fraud were the real reasons for this success). However, towards the end of his second term, Marcos declared Martial Law, clutching on to power with the excuse of ‘reforming society’ after facilitating economically tumultuous years and rising critical voices. The Martial Law years were the Philippines’ darkest since independence, but the regime was eventually toppled by the peaceful 1986 People Power Revolution. With the Marcos family fleeing to Hawaii (their flight into exile organised by US president Ronald Reagan), protesters stormed Malacañang, the presidential palace, and discovered the ostentatious remnants of the family’s lifestyle. Indeed, the myth of Imelda’s 3,000 pairs of shoes made global headlines and strategically eclipsed the atrocities committed by the family, as well as a legacy that left the country economically reeling from a $26 billion debt and 44.2 percent poverty rate. With the family’s departure, the objects Imelda used to cultivate a notoriously opulent and garish image also seemed to disappear over time. So far, the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) – a taskforce designated to find and repatriate the Marcoses’ missing wealth – has recovered what is estimated to be less than 10 percent of all illicit assets.

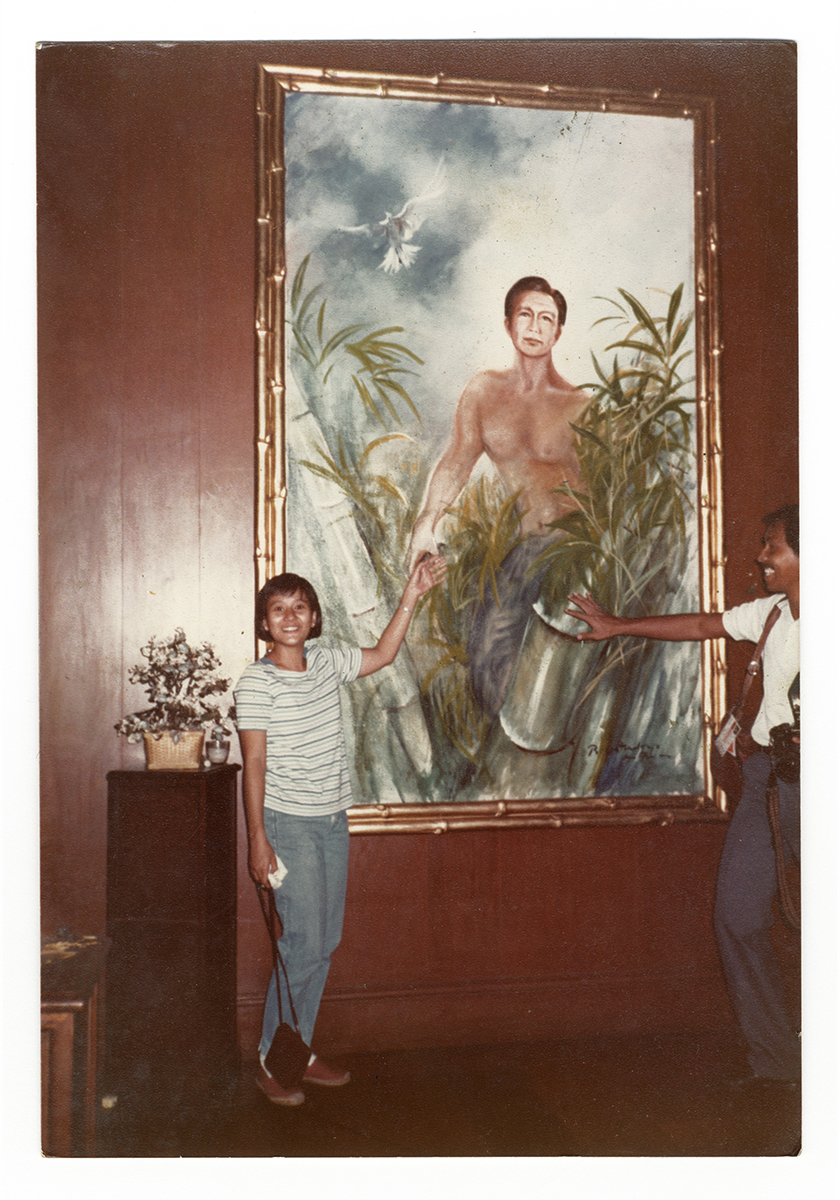

Abad’s parents were among the first activists to enter Malacañang. The artist says this project really began with a photograph his mother took of his father from that day, where he posed with an enormous, mythologised portrait of Ferdinand Marcos painted by Evan Cosayco. In this portrait, a ridiculously taut Marcos emerges from a split bamboo in the middle of an idealised forest with a dove flying overhead. The partner portrait shows Imelda, donning a flowing white dress, similarly blooming into the world. These romanticised portraits of Ferdinand and Imelda envision them as the first Filipinos from mythology – Malakas (the Strong One) and Maganda (the Beautiful One) – disseminated as propaganda to position the couple as the parents of their envisioned Bagong Lipunan (New Society, based on Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society). Abad first saw these paintings at ten years old, but when he visited the palace again in 2010, they had been removed and hidden away. The best way to see these again, he decided, was to make his own to-scale reproductions, which he explains in a 2019 lecture is an “elaborate disavowal of violent political fantasies, laundered histories and alternative facts”. Revival aside, Abad brings the images into contemporary spaces, relying on the privilege of retrospection to endow them with the isolated absurdity that only distance can afford. During the Marcos era, these propagandistic paintings spread a parental, authoritative message. In 2010, 21 years after the patriarch’s death in 1989, the Marcoses did not wield the same influence they had in the twentieth century, despite Imelda winning a seat in the House of Representatives that year; in the reproductions, the Ferdinand and Imelda of the Martial Law years take on a new form.

However, when President Rodrigo Duterte allowed Marcos’s body to be buried in Libingan ng mga Bayani (Heroes’ Cemetery) of Manila in 2016, ending the family’s decades-long campaign, Abad decided to cover these reproductions with black paint, in a recorded, performative gesture at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Manila, where they were on view at the time. In a letter to the museum, Abad writes: ‘I just know that this isn’t the time to be talking about the whimsical fantasies of a dictatorship. It is the time to confront the painful realities the Marcoses have continued to inflict on the Filipino people and what that means for the country and for the region. I would like to somehow implicate these works in an act of indignation.’ Marcos’s apparent acceptance by the Philippine government signifies historical revisionism wherein he is restored to the heroic status he desperately manufactured during his lifetime. Abad notes in a lecture that this is the kind of “symbolic restitution that democracies have sought since their temporary defeat – as if this burial was an act of justice for the family”.

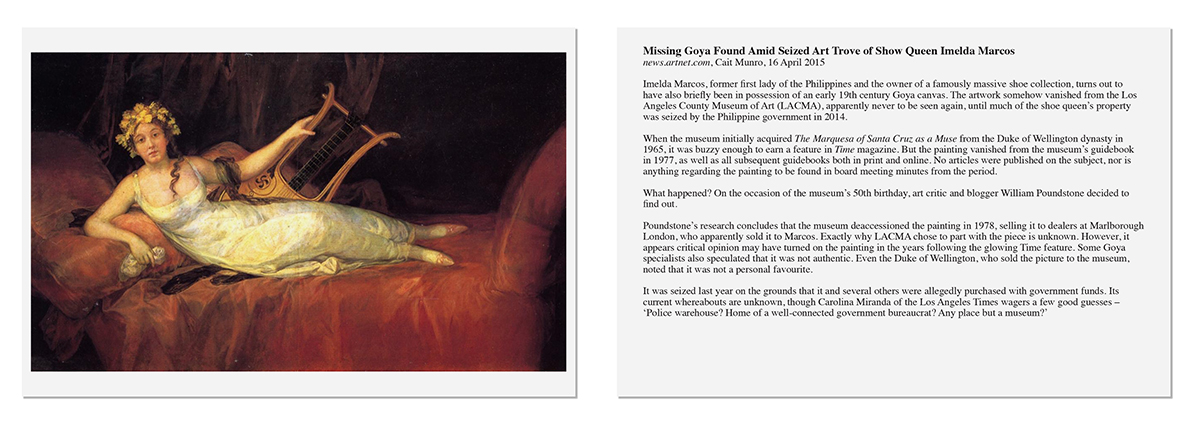

The first presentation of The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders is composed of an unlimited number of postcards that feature artworks Abad has identified as belonging to the Marcoses. Typically, these are displayed on two long plinths; viewers are encouraged to take away copies of the postcards as an alternate act of repatriation. By ‘redistributing’ these artworks, Abad claims to ‘return the collection to its rightful owners who unknowingly purchased the works but never really enjoyed its visual benefits’. Instead of including an art historical blurb about each painting on the back of the card, Abad appropriates news articles that recount the object’s history. On the back of one postcard, of a 1805 work by Francisco de Goya, The Marquesa of Santa Cruz as a Muse, Abad cites a 2015 Artnet article by Cait Munro: ‘The artwork somehow vanished from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), apparently never to be seen again, until much of the shoe queen’s property was seized by the Philippine government in 2014’. The painting continues to be missing according to missingart.ph, a nonexhaustive public list set up by the PCGG to increase the profile of the restitution project.

Succeeding versions of the project include reproductions of other artworks – sculptures, paintings and photographs – owned by the Marcoses, while the most recent iteration of The Collection…, unveiled at Honolulu Biennial, in 2019, is a collaboration between the artist and his wife, fellow artist and jewellery designer Frances Wadsworth Jones. When the Marcoses were exiled to Hawaii in 1986, they brought with them over 35 pieces of luggage containing 413 pieces of jewellery, which were seized upon arrival and repatriated to the Philippines for liquidation by the PCGG. Known as the Hawaii Collection, the jewellery was consigned by the Philippine government to Christie’s for auction in 2015, 30 years after its confiscation. However, in June 2016, President Duterte swiftly cancelled the sale, asserting that it could only proceed if Imelda were allowed to bid. The collection has not been seen since. For this phase, Wadsworth Jones adapted Christie’s 2D photography so that the jewellery could be 3D-printed in white plastic. These beautiful bijoux are ghostly traces – allowing them to be seen by the public (albeit in an alternate form) for the first time in over 30 years. Their status as objects and property is purgatorial, with Abad’s artworks functioning as traces of what exists but remains missing.

And perhaps this is what’s important in Abad’s project: he doesn’t find and revive the original, disappeared treasures; he creates new, spectral copies that endow an afterlife beyond the objects themselves, affording them a sort of freedom to be seen while their real, primary forms exist in ambiguity. Abad’s new objects function in a Proustian act of remembrance that not only seeks to catalyse forgotten memories, but also grievances. These spectral works exist parallel and adversely to the Marcoses’ real ill-gotten gains and manufactured narrative. Abad positions each new object, resurrected from forensic indexes in verified historic reality, against the real articles and pushes them further into the Marcoses’ manufactured narrative of delusional grandeurs and ‘edifice complex’ (a term coined by Filipino artist and activist Behn Cervantes to describe Imelda’s rapid construction of institutions, touted to promote Philippine talent, but only fostering Western and Eurocentric standards in practice).

More personal to Abad is the family tradition: The Collection… begins with his parents and collaborates with his wife. However, Abad particularly reminisces upon the legacy left behind by his mother, who has since died: “It’s her loss that has defined the work,” Abad said in his 2019 lecture, “since it wasn’t coincidental that my mother died as the country that she sought to create fell into pieces: an entire nation’s social cancer became her own” (José Rizal’s 1887 novel, Noli Me Tángere, was translated into The Social Cancer in 1912). With the Marcoses own familial legacy again gaining popularity and relying on generational succession, the ghosts of the past cannot be forgotten.

Marv Recinto is a writer based in London