Through physical and virtual realities, the artist addresses a wide array of subjects, from his identity as a Black trans American to the climate crisis

It’s tempting to draw a line between physical and virtual realities, but each one bleeds directly into the others. Lived reality is virtual reality is augmented reality, as Rindon Johnson’s expansive practice evidences. The California-born, Berlin-based artist’s work encompasses media ranging from virtual and augmented reality to physical sculpture and materials like leather, wood and stone; he addresses topics equally wide-ranging, from his identity as a Black trans American to the global climate crisis. Johnson, as he writes in his most recent book, The Law of Large Numbers: Black Sonic Abyss (2021), refuses ‘to walk a line that is thin, straight, or secure’. But the roots of his works can all be traced back to one thing: language.

coloured pencil, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly,

Los Angeles & New York

Johnson has authored four books to date, including Meet in the Corner (2017), a book that can only be read – or, rather, experienced – in virtual reality. The Law of Large Numbers is an artist’s book that also acts as the catalogue for his two-part exhibition, Law of Large Numbers: Our Bodies, currently on view at SculptureCenter in New York, and Law of Large Numbers: Our Selves, set to open later this year at Chisenhale Gallery in London. In Johnson’s practice, the format of the book provides context and adds a multitude of additional layers to his sculptural and digital works. Beyond books, each of his artworks also begins with a set of questions, often along the lines of, ‘What is something called, why do we call it that and what can be done about it or what can be changed?’ Language is a fundamental part of his practice, because, as he says during a Zoom studio visit, it is “the most liberatory thing we’ve got”.

Take, for example, Coeval Proposition #1: Tear down so as to make flat with the Ground or The *Trans America Building DISMANTLE EVERYTHING (2021). Without the lengthy appellation, it would appear to be a large redwood sculpture consisting of two simple concentric pyramids, one slightly smaller and inverted. Through the title of the work, however, Johnson reclaims one of San Francisco’s most iconic buildings for himself and any other trans person who wants it. The geometric formation becomes an ebonised outline of the Transamerica Pyramid, built by the titular insurance and investment corporation in 1969. This work embodies what artist Matt Keegan has said: biography and identity are tools to stake a claim. ‘I believe this is my building,’ Johnson writes in The Law of Large Numbers, ‘so it is my building.’

The opposite approach to such a conceit is found in his virtual-reality film Meat Growers: A Love Story (2019), which addresses gender and race in the form of absence. The characters remain androgynous and their races ambiguous as they navigate a post-Green New Deal Napa Valley. In the speculative fabulation, strip malls have been replaced with food forests and meat-growing plants, there are no paved roads in sight and the viewer’s character carpools to work in a solar-powered Volkswagen Beetle. The narration provides poetic ruminations on love and longing, on exploitation and sustainability, while the chosen media provides a space fit for making the world anew.

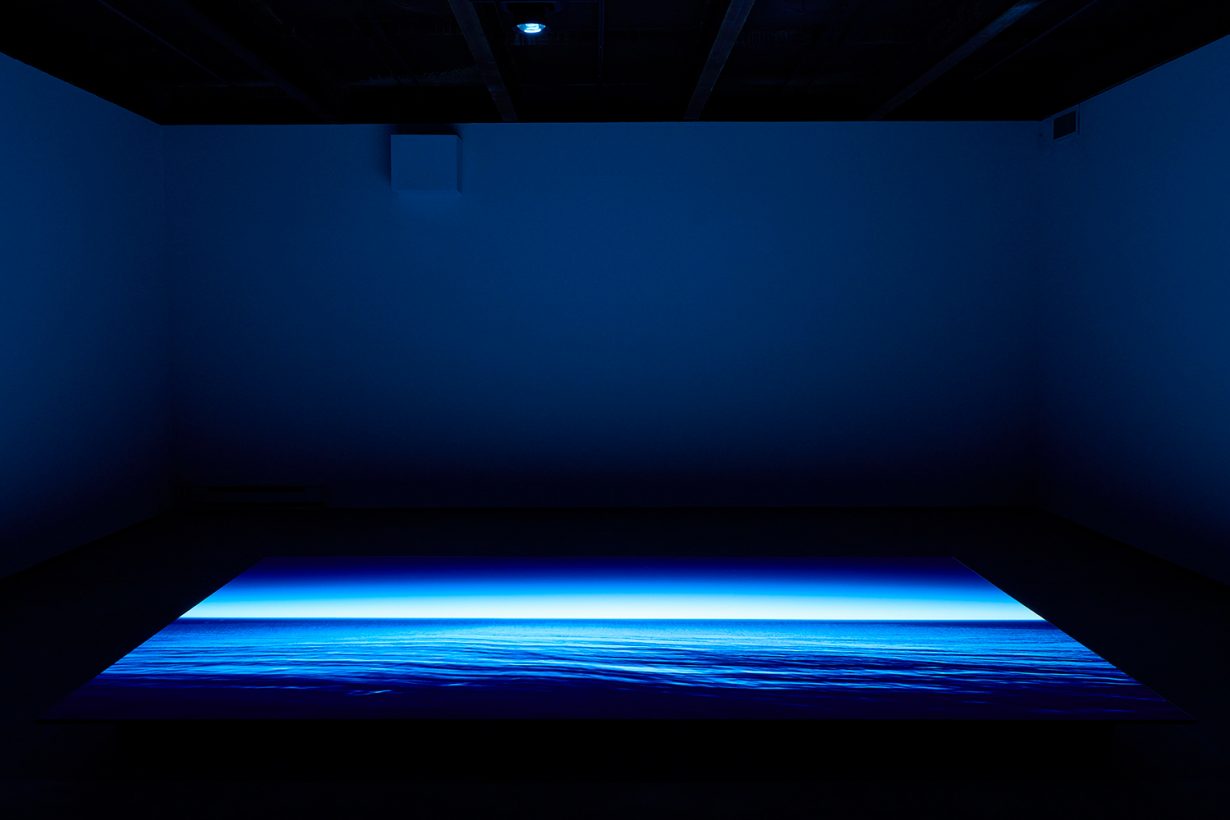

Our ecological crisis – with an underlying, though visually absent, reflection on race – is also seen in Coeval Proposition #2: Last Year’s Atlantic, or You look really good, you look like you pretended nothing ever happened, or a Weakening (2021). For this installation, Johnson collected ocean weather-data for 24 hours a day from March 2020 through January 2021 to create a live video projection that figuratively visualises the information. For the duration of the SculptureCenter and Chisenhale shows, the ocean reflected back to visitors will be as it was in that exact moment one year prior. From Johnson’s perspective as a Black American, the Atlantic Ocean is a space imbued with meaning, but the work also functions on another level: the exact midpoint between the New York and London exhibition venues happens to be in the middle of the North Atlantic ‘cold blob’, or ‘warming hole’, an unusual manifestation of global warming that is critical to our understanding thereof. In brief, the blob is a cold-temperature anomaly of ocean water that contributes to the slowing of the Gulf Stream. The blob’s growth could, in theory, prevent – and is likely, at the bare minimum, to redirect – the flow of warm water that usually moves upwards past the British Isles and Norway. And, as Johnson asks in the catalogue, ‘What happens without the Gulf Stream? Nothing Good.’ He then brings the piece full circle: ‘We are going to be victims of the systemic generational hubris of those crap industrial, colonial ancestors, fellow humans, and selves.’

In addition to technology and language, it must be said that cows also play a significant role in Johnson’s practice. This is to be considered an amazing place. (panel #1) (2020), an abstract drawing with coloured pencil on varnished leather, is an example of his ongoing experiments with cowskins, while in his virtual reality experience Diana Said: (2019), cows appear as the sole creatures. Johnson first used leather and rawhide in 2018 in the same vein that artist Susan Rothenberg used the horse: he didn’t hate cows, but he also didn’t particularly like them; he had no real relationship to them. They were enough of a nothing that they could be a form. But soon he felt a kinship with the pieces of leather and rawhide, or ‘cows’, as he endearingly calls them: they are byproducts of a vicious process, as are Black Americans. Now, three years later, he goes so far as to write in The Law of Large Numbers, ‘We are coeval, the cow and myself, and by making the work, creating the work, and then selling the work away, we remain coeval.’

During our studio visit, Johnson takes me to a sun-drenched field in Sonoma, California, where he’s currently working – a change of scenery from his adopted home of Berlin. When he flips the camera on his phone around, his face is replaced with a number of ‘cows’ on a tarp. A piece of purple furniture leather is covered with rusted pipes, a blue one with broken cinderblocks and shellac. The leathers have been exposed to the elements for at least 18 months and are being made in the same way as For example, collect the water just to see it pool there above your head. Don’t be a Fucking Hero! (2021–) – a large piece of rawhide that has been suspended with white cotton rope outside, above the entrance to SculptureCenter, since January. Soon some of the cows will leave the field and travel to Los Angeles, where they’ll be presented – from mid-May – at François Ghebaly gallery. Yet the cows will continue to react to the elements and their surroundings. Johnson’s works are intentionally never fixed, never sealed to a point where they’re unable to change. “I would hate to make a work that is static,” he says.

Just as the elements will continue to make their marks on these cows, the wood used to make Coeval Proposition #1 will eventually decompose. Similarly, a viewer will never have the same experience twice when viewing works like Coeval Proposition #2, Meat Growers: A Love Story or Diana Said:. In this regard, the only fixed aspect of Johnson’s practice is the written word – the titles, texts and books forever intertwined with both his physical and digital works. But even these should not be deemed a constant. While words can be used to name and describe, they can also create chasms and suggest paradigm shifts, as is often the case with Johnson’s practice. They can instil new forms of thinking where other modes of perception fail. Such is the power of language.

Rindon Johnson’s Law of Large Numbers: Our Bodies can be seen at SculptureCenter, New York, through 2 August. His exhibition The Valley of the Moon is on view at François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, through 19 June. Law of Large Numbers: Our Selves opens at Chisenhale Gallery, London, in November. And a collaborative exhibition, This End the Sun, with Maryam Hoseini and Jordan Strafer, is on view at the New Museum, New York, 30 June – 3 October

Emily McDermott is a writer and editor based in Berlin