Featuring Zarina Muhammad, Jala Wahid, Fukushima art, Thai cinema, and an artist project by Kaylene Whiskey

The Winter issue of ArtReview Asia looks to the ways in which stories and narratives originate, then morph and adapt to our contemporary times.

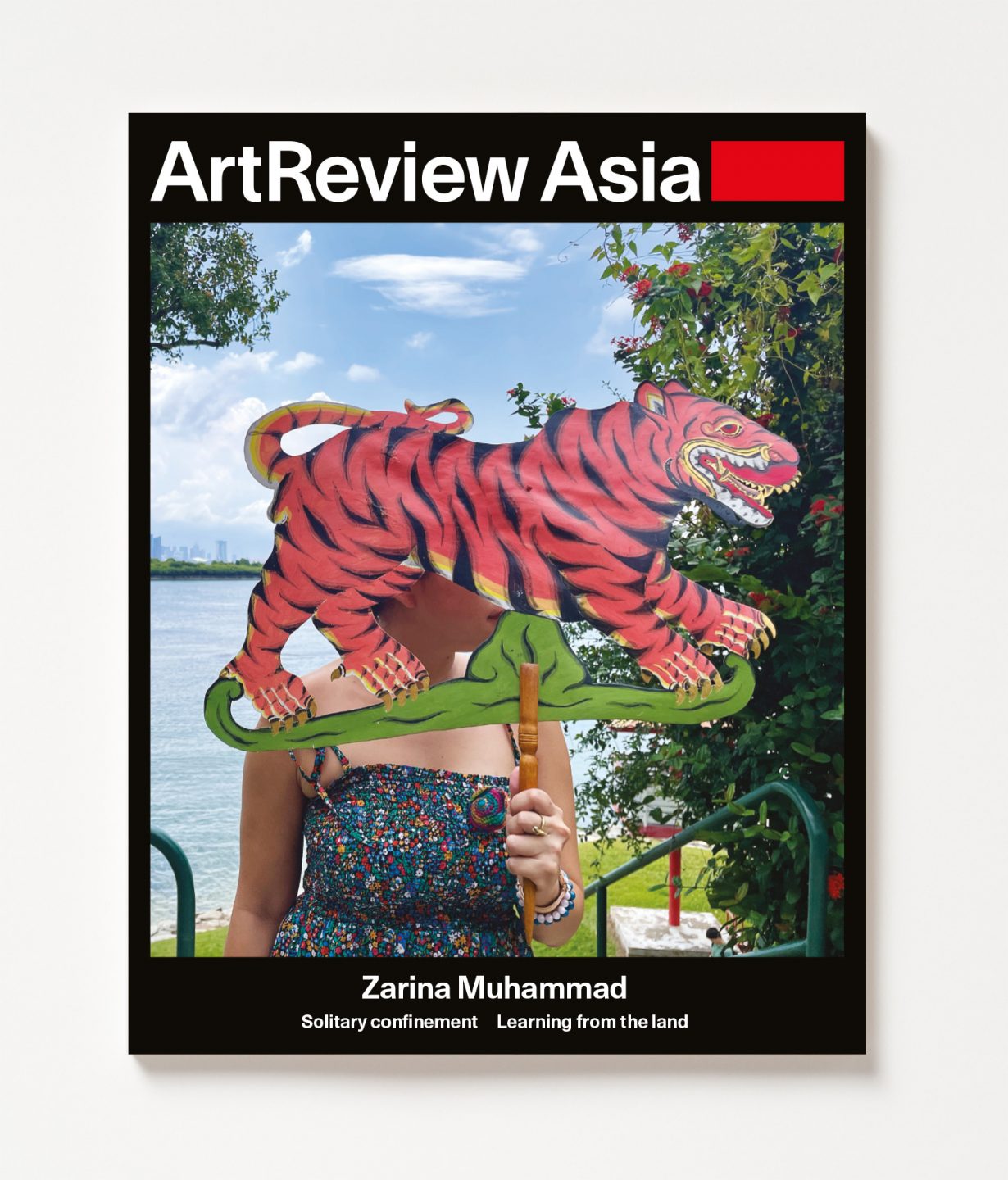

The cover features Zarina Muhammad, a Singapore-based artist whose practice engages otherworldly responses to the current crises of environmental collapse and extractive capitalism via performance rituals and shrine-building. ‘In Zarina’s work, magic, myths and mysticism are put forth as valid ways of navigating a complex and uncertain world,’ writes Adeline Chia. ‘On a practical level, she argues that rituals, charms and spells offer psychological comfort and guidance through difficult times. But her other proposition is metaphysical: that there is a rich and hidden world of ghosts, gods and guardians of which the human is only a small part.’

Jala Wahid’s most recent excavations into how the oil industry has affected Kurdish land rights also seek out nonhuman voices, in an expansive soundscape presented at Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead. ‘The artist brings the viewer back to the material reality that informs, among other things, the making and unmaking of cultural identity,’ writes Sarah Jilani. ‘There are lands in which people are rooted, and the struggle over ownership of precious materials in these lands too often determines which people will, or will not, be positioned as citizen, refugee or collateral damage.’

Meanwhile Aboriginal artist Kaylene Whiskey’s paintings and videos are inspired as much by tradition as they are pop culture. In a portfolio feature of the artist’s work, Fi Churchman looks to one example of the Aboriginal creation stories, collectively known as songlines, that inform Whiskey’s works and traces the ways in which the artist blends contemporary references to female pop culture personalities like Tina Turner and Wonder Woman with ‘strong women’ figures from traditional Aboriginal culture.

Tyler Coburn interviews three creatives from his covert writing residency at the prisonlike Happitory (‘Happiness Factory’) in Hongcheon, South Korea. Set up in 2013 by Kwon Yong-seok and Noh Jihyang, the wellness centre is a place where people who are feeling overwhelmed by the stresses of daily life can check themselves in for a stay. Deprived of distractions such as books and electronic devices, each ‘inmate’ is locked into solitary confinement and provided with only a few items: a yoga mat, a tea set, bedding and pens and paper.

In our columns section, Max Crosbie-Jones explores the Thai Film Archive in Bangkok, while Taro Nettleton ventures into Fukushima’s exclusion zone to revisit an artwork that was first on show at the Chim↑Pom-organised exhibition Don’t Follow the Wind in 2015. Plus books and exhibition reviews from around the world including Busan Biennale, Istanbul Biennial and Aichi Triennale.