At the close of the long twentieth century, as humanity prepared to cross the artificial border set up between one millennium and the next, it seemed as if all the ossified boundaries we had so carefully constructed in the past were being violently destabilised by the looming threat of an uncertain future. In an increasingly globalised artworld, questions of identity, difference and otherness were all the rage. Controversial exhibitions like the 1993 Whitney Biennial in New York and Sensation (1997) in London put questions of race, gender, politics and sexuality front and centre of art-historical debate. Critical theory too was seized by an apoplectic proliferation of ‘post-isms’ – postmodernism, poststructuralism, postfeminism, postcolonialism, post-socialism and the posthuman – that apocalyptically intoned the end of all grand narratives.

It was in this context that the Korean artist Lee Bul first emerged onto the New York art scene in 1997, in a joint exhibition with the Japanese artist Chie Matsui, at the Museum of Modern Art, no less. Lee’s offering was a work titled Majestic Splendor (1997) – a glittering installation of freshly caught fish, each meticulously encrusted with sequins, beads and gold flowers; some displayed in deodorised clear-plastic bags, others enshrined in a refrigerator. Despite these sanitising measures, the nauseating miasma of decaying flesh soon permeated MoMA’s hallowed halls, resulting in the exhibition’s premature closure.

While the failed utopias of the past would similarly return to haunt Lee’s practice, it was initially her evocative visions of the future that made her one of the most prominent non-Western artists of an anxious age

In a heady artistic climate primed for divisive displays of cultural difference, Lee’s succès de scandale only served to further her ascent in the global arena. A simulacrum of her MoMA piece was permitted to rot away at Harald Szeemann’s Lyon Biennale the same year, in a group show tellingly titled L’Autre (The Other). Lee was subsequently nominated for the Hugo Boss Prize in 1998, and selected to represent South Korea at the 1999 Venice Biennale (having already been included in Szeemann’s curated exhibition) – the year that another East Asian artist, Cai Guo-Qiang, won the coveted Golden Lion award for his controversial Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard (1999), a crumbling, recreated work of socialist realist propaganda. While the failed utopias of the past would similarly return to haunt Lee’s practice, it was initially her evocative visions of the future that made her one of the most prominent non-Western artists of an anxious age.

To date, Lee is still perhaps best known for her Cyborg series (1997–2011) – robotic, sexualised silicone figures, prosthetically augmented and techno-organically enhanced. Lee’s Cyborgs signposted the culturally specific influence of manga and anime, while simultaneously embodying the global fantasy of a future perfect, in which genetic engineering, cloning and cosmetic surgery would smooth over all the messy anxieties of the present tense. A companion piece to the Cyborg series was the participatory and populist work Live Forever (2001) – futuristic karaoke capsules that echoed the streamlined aesthetics of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), set in the same year. Spectators were invited to enter Lee’s snug padded pods one by one and sing themselves into a solitary oblivion, keyed in the soporific tenor of Huxleyesque mass delusion.

At the opposite end of the scale, Lee’s other well-known series of work from the late 1990s gave gruesome shape to our worst biotechnological fears, in a period marked by hysteria over the Y2K bug, the start of the Human Genome Project, the commercialisation of genetically modified crops and the birth of Dolly the sheep. The sculptures and drawings of Monster (1998/2011) and Anagram (1999–2005) consisted of a host of amorphous, densely textured organic forms, overspilling with limb-like protrusions, evoking the psychic horror of the uncanny as well as the sci-fi nightmare of alien predation, the nightmarish progeny of Louise Bourgeois and H.R. Giger.

It’s easy to see why Lee’s work from the turn of the millennium has so often been read as the artistic equivalent of Donna Haraway’s seminal ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist-Feminism in the late 20th Century’ (1991), a text that Lee has credited as an influence. For Haraway, and initially for Lee, cyborgs and monsters functioned as powerfully ambivalent metaphors; ciphers of resistance against the traditional limitations of gender, feminism, race, science and politics. Their hybrid ontology embodied the collapsing distinctions between (wo) man, machine and animal at a time when the boundary between science fiction and social reality appeared to be little more than an ‘optical illusion’. Ironically, Lee found herself pigeonholed as the quintessential ‘Asian woman artist’, just as Haraway’s theories were increasingly ‘co-opted by the spectacle of the techno-sublime, manufactured by the computer and biotech industries’, as Lee lamented in an interview with Kim Seungduk in Art Press in 2002. But the artist has proved herself to be nothing if not adaptable, and her work soon evolved in an unexpected direction. While the cyborg and monster series seemed to embody Jacques Derrida’s proposition that if the future can only be defined as an absolute break with constituted normality, then it can only be ‘proclaimed, presented as a sort of monstrosity’, Lee’s more recent works entertain another possibility, proposed by Vladimir Nabokov – that the ‘future is but the obsolete in reverse’.

Beginning in 2005, Lee turned to the past in order to explore the history of imagining the future. The ongoing Mon Grand Récit (2005–) series is an eclectic body of immersive installations, drawings and sculptures that foreground Lee’s intellectual and artistic engagement with literary, philosophical and architectural meditations on utopia and dystopia, state fiction and social reality. Mon Grand Récit: Weep into Stones… (2005) is a surreal assemblage that combines geological and mineral forms with fragmented architectonic structures. A glowing white limestone formation – based on Hugh Ferriss’s otherworldly 1930 description of a skyscraper of the future – emerges from what looks like a chunk of asteroid rock, incongruously suspended on a gridlike scaffold of aluminium rods. This central tower is encircled by a spiralling wooden highway and studded with miniature replicas of bleached architectural icons, including Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1920) – that soaring emblem of a socialist new world order that was never realised. In a similar vein, Mon Grand Récit: Because Everything… (2005), consists of fragmented architectural forms haphazardly embedded into a molten surface of white and pink resin, like the ruins of an alien civilisation devastated by some sort of cataclysmic eruption, petrified in a state of collapse.

These large-scale topographical installations chronicle the dreamworlds and catastrophes of utopian desire, focusing particularly on the febrile imaginariums of twentieth-century modernist architecture

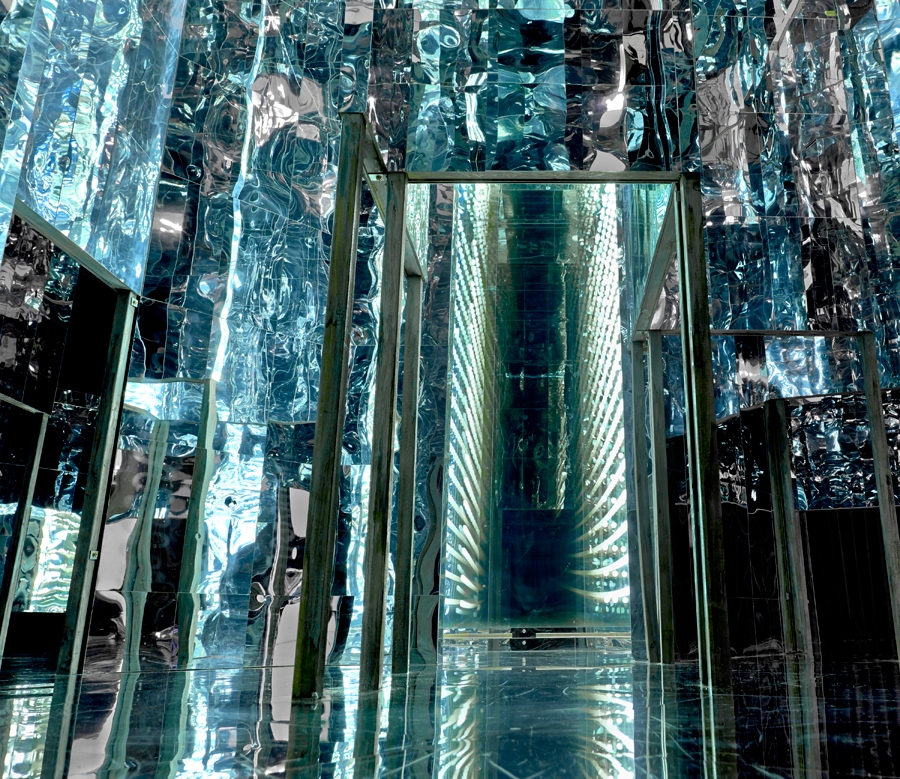

These large-scale topographical installations chronicle the dreamworlds and catastrophes of utopian desire, focusing particularly on the febrile imaginariums of twentieth-century modernist architecture. One of the most powerful manifestations of this is After Bruno Taut (Beware the Sweetness of Things) (2007) – a suspended, chandelier-like structure, dripping with crystalline beads and overlaid with a dense patina of chainmail. The work is inspired by the expressionist architect Taut’s fantastical visions of an ‘Alpine Architecture’, drawn up just before the end of the First World War and the collapse of the German empire. In dialogue with the science-fiction writer Paul Scheerbart, Taut proposed to divert mankind’s energy and resources away from war and conflict, towards constructing dazzling cities made of crystal and glass that would complement the natural landscape and eventually even extend to the stars. Lee’s opulent homage to Taut’s feverish optimism hovers precariously in midair, as if on the verge of crashing to the ground.

Indeed, as Fredric Jameson observed in his book Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions (2005), ‘Utopians, whether political, textual or hermeneutic, have always been maniacs and oddballs: a deformation readily enough explained by the fallen societies in which they had to fulfil their vocation.’ And indeed, the same could be said of Lee herself. It is here that the artist’s personal biography intertwines most poignantly with her practice. Lee was born in 1964 to dissident parents in Seoul, during the US-backed military dictatorship of Park Chung-Hee. She graduated from Hongik University in 1987, the year of the first democratic elections, which promised to usher in a new era; a dream of the future that was all too often dashed by the traumatic legacy of totalitarianism and the alienating spectacles of rapid urbanisation and economic development. Rejecting the overtly political social realist aesthetics of the Minjoong movement, Lee instead took to the streets in a series of outrageous performances, dressed in a soft-sculpture monster suit that was a precursor of the later posthuman experimentations with corporeality that came to define her practice.

The visual splendour of Lee’s work is always undercut by a latent sense of foreboding

More recently, Lee has begun to make more specific references to the political history of Korea. Thaw (Takaki Masao) (2007), for instance, is a pale pink iceberg formation that, upon closer inspection, reveals an eerily lifelike replica of Park Chung-Hee, cryogenically frozen within its glacial embrace. Park, who also went by the Japanese name parenthetically cited in the work’s title, was a man whose idealistic, socialist dream for a better future mutated into a fascist nightmare for an entire nation. Lee is no doubt fascinated by his fall from grace, and arguably still haunted by his memory. The visual splendour of Lee’s work is always undercut by a latent sense of foreboding, also reflected in their ominous titles – warning, weeping and thawing – the last implying the threat of a brutal dictator slowly defrosting from an icy slumber, with the potential to rise up again at any time.

In our present era, a so-called age of terror, our retinas are permanently imprinted with mass-mediated images of carnage, catastrophe and crisis. A sense of threat is perhaps one we can all identify more easily with in the present than the utopian impulses of the past, which appear to be little more than the foolish dreams of an altogether more innocent epoch. Perhaps the last of our utopian ambitions did indeed end with the events of 9 /11, and as Franco Berardi put it, ‘the artistic imagination, since that day, seems unable to escape the territory of fear and despair’.

Lee’s work does not offer us any immediate solutions to this predicament. Indeed, Mon Grand Récit translates as ‘my grand narrative’ – a melancholic riff on Jean-François Lyotard’s famous pronouncement that the postmodern era signalled the end of all grand récit – the grand or meta- narratives that characterised modernity. By adding the prefix mon, or ‘my’, into the title of these pieces, Lee attempts to salvage her own history from the ruins of the past. Similarly, her work encourages the viewer to forge critical links between the fallen societies of recent history and the precarity of the present, to question our own grandiose constructions and assume personal responsibility for a shared future we can only ever imagine.

Lee Bul’s work is featured in the Gwangju Biennale, 5 September – 9 November 2014. Her first UK solo exhibition runs at Ikon in Birmingham, 10 September – 9 November 2014, with an accompanying exhibition at the Korean Cultural Centre in London, 12 September – 1 November 2014. Lee will also present a new large-scale commissioned work at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, on 29 November 2014.

This article was first published in the Autumn & Winter 2014 issue of ArtReview Asia.

12 September 2014