Three artists from Yangon describe acts of creative dissent on the streets, as hundreds of thousands defy the military coup

Dissent in Myanmar continues to roil, following a military coup on 1 February which placed Aung San Suu Kyi and other leading politicians under arrest. Hundreds of thousands have rushed to the streets in defiance of harsh police crackdowns – the largest, and most diverse series of mass protests in more than a decade. Meanwhile, the military government has moved to suspend court orders for detainment of suspects, and their response to the protests has grown ever more deadly. Despite the intermittent Internet blackouts, three artists from Yangon have written for ArtReview about the experience of the coup on-the-ground, the role of art for protesters on the streets, and their hopes for the future.

Our Freedom Is at Stake: the Artivism of the Myanmar Protests

By Sai

The first day of February broke with the news that Aung San Suu Kyi had been detained. ‘What a sick joke,’ we thought, until the BBC confirmed a coup was under way. Trying to fathom what was going on, I still was not ready to accept the news. Immediately, I called my parents who live in Taunggyi only to find out that their phones were not working. I later discovered that my father, a politician, had also been detained. My partner immediately responded to the chaos by packing, not knowing what would happen next. My Facebook account has been tracked by fake accounts since November – I sensed something was coming.

Rushing to a secure location at 6 in the morning, I sent a voice message to a lawyer friend from the US, informing them of the situation. That is the only message that got out before the Internet was cut off across the country. My whole family has since been placed under house arrest. We do not have any idea about the whereabouts of my father and uncle. By breaking their own constitution, the military has arrested hundreds of innocent people, including politicians, activists, protesters, writers, artists, students, doctors and many more. Last week, police shot a teenager in the head during a protest in Naypyidaw.

All our rights will be gone: a typical Orwellian society. Myanmar goes from coup to coup, and the country deteriorates each time. It is beyond question that civil wars, genocide and human rights violations have their roots in the military. Many of us took it for granted that going backwards is not something to be expected. We had glimpsed progress. People dream of life beyond the military: a true democratic nation. This coup is the opposite of what the people hoped for. Lives are at stake; dreams are seized.

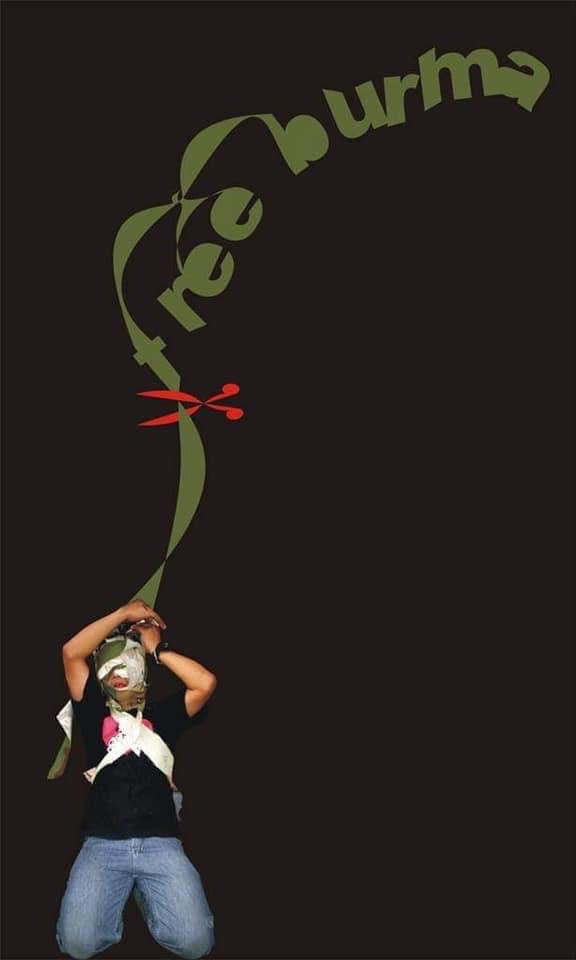

But as an artist-curator and activist, I have witnessed a new art form: the art of protest and civil disobedience. I have been shaken to the core by this collective artivism which beats everything I have seen before. Creativity is at its peak: people have been grabbing international attention to get their message across while resisting the coup. They truly messed with the wrong generation and the wrong time. Youth is the driving force of this protest movement against the coup’s leader, general Min Aung Hlaing. On the streets, protesters have drawn on memes, humour and cosplay; coffins of the dictator have been burnt; prayers sent for the spirits to punish the general; farmers, LGBTQ activists and musicians protesting peacefully and screaming their hearts out to reclaim freedom. So, if you ask me, they are the true artists here; protest is their stage.

Last year, I was making plans for the Kalaw Contemporary Arts Festival in Myanmar. Now, everything has gone. I worry: what will happen to my family? Will the military continue killing people? We have no idea at all what the future would be like. Our freedom is at stake. Will we live or die? We don’t know yet. But we will die struggling for a democratic future, rather than being barely alive in a dystopian society.

Sai is a Yangon-based curator, artist and peace educator. He was a recipient of a Goldsmiths Fellowship from the University of London in 2019.

‘We Are Entering the Dark Again’

By Aye Ko

The coup is a stain on Myanmar’s society and democracy. Massive numbers of citizens, artists, students, workers in different fields and business are out on the streets to raise their voices against the military coup, against the threat to justice, human rights and freedom of expression.

I see youths very active in the movement against the military coup. They have been using social media and technological platforms to fight back against injustice. They are connected faster – being on the streets is not the only option for them; they have also found other ways to fight against the coup. During the 1988 pro-democracy protests, it was difficult to stay so connected or to connect with other people quickly.

Artists are also engaged in charity work to support the Civil Disobedience Movement; others have connected to international artists to support the movement online. We are entering the dark again. But I have faith in all of us – including artists – that we can break down that dark wall with our heads.

Aye Ko is an artist and former political prisoner from Myanmar. He is a cofounder of New Zero Art Space.

How the ‘Hunger Games’ Inspired a Symbol of Defiance in Myanmar

By Moe Satt

On 1 February, when I woke up and checked my mobile phone, I noticed that there was no Internet connection. I worried a little. When I opened the door to come out, I met my neighbour. She told me that our president Win Myint and state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi had been arrested and that the army had seized state power. Wow! We are back in the Dark Ages. I have had more than 20 years of being oppressed by the military dictatorship. I don’t want my son to undergo the same thing. I don’t want him to grow up in a culture of fear.

That evening, people started to protest by beating pots and pans. On the first day, only a few households took part. By the second day, spread by word of mouth, more and more joined. First, they beat for five minutes, and then longer and longer. Our people’s anger became stronger and stronger, rising like a tide. The tide must retreat at a certain time, but our people’s anger and resentment rises further. When I travel around Yangon, I see another campaign of blown car-horns. When cars pass by other cars, their drivers honk and raise three fingers. The sound of car-horns now fills the whole of Yangon.

We take selfies of our three fingers raised – a sign of rebellion against the military coup. Once a symbol of dissent in The Hunger Games (2012); now a sign of our revolution against military dictatorship. During the day, food and drink are distributed to the protesters (leading to the saying, ‘revolt against dictatorship, eat eggs’). At night, on the walls of tall buildings, we can see huge projected pictures and text – the work of Generation Z – urging us to take part in civil disobedience, to restore power to the people.

Our artists’ group, the Association of Myanmar Contemporary Art, has been busy raising funds for the Civil Disobedience Movement, by selling our artworks in front of the High Court in Yangon. On the first day, more than 50 artists and musicians came to take part in the movement of making art and fundraising.

This is the endgame for both the citizens and the army. On 10 February, the police shot a girl of nineteen, a peaceful protestor. Netizens swiftly identified the police officer responsible: his home and businesses. If society ostracizes his family as the family of murderer, perhaps future killers will be deterred. Will dictatorship survive? Or will the people win? We must not let this revolution be long.

Moe Satt is an artist in Yangon, Myanmar. He is the cofounder of Beyond Pressure, an international performance art festival in Myanmar.