QUAD, Derby

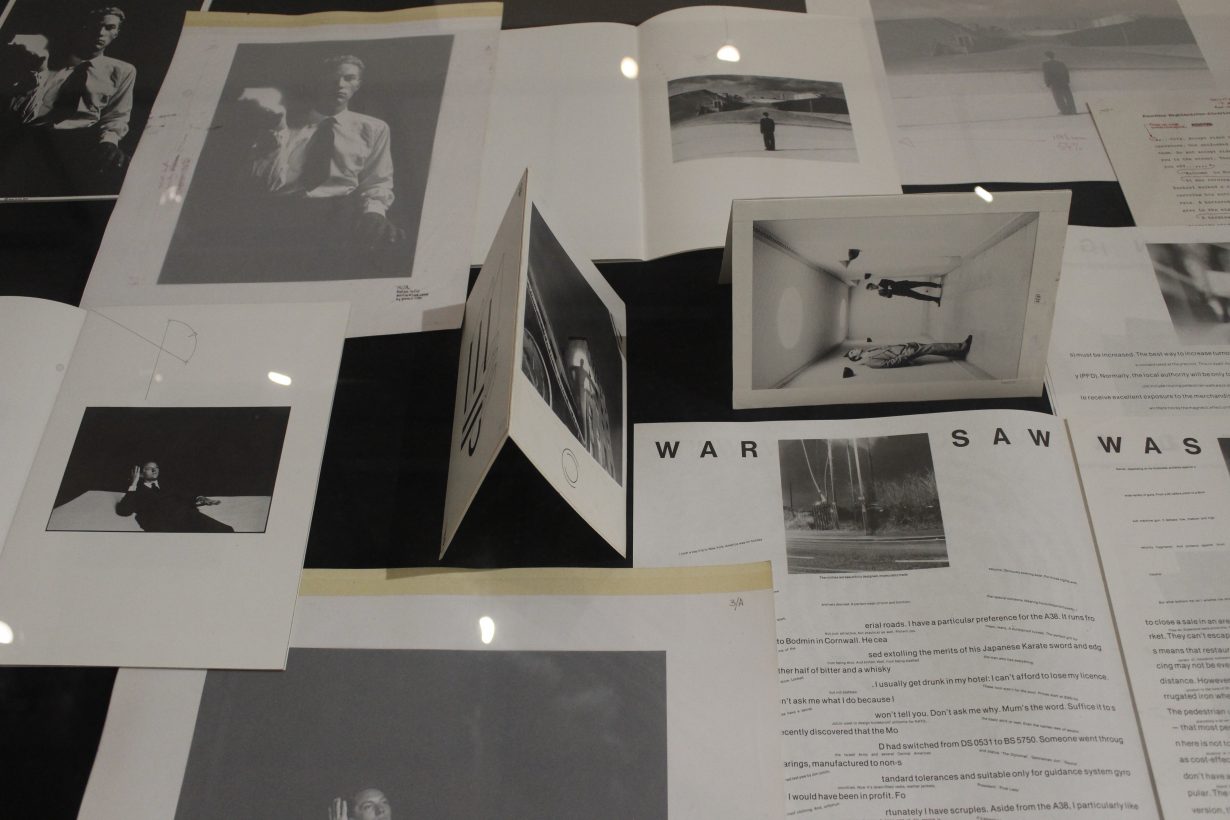

Where have the workers gone? It wasn’t so long ago that broad-backed men toiled drudgingly on factory-floor assembly lines, proud faces coated in grime. Now the heavy industries are a myth, all but vanished. Yet their forgotten presence still lingers in the stark black-and-white photography of Brian Griffin. In Black Country Dada:1969–1990 we enter into the bleak industrial landscape that once dominated much of the West Midlands. A region that rapidly transitioned, accelerating towards a post-industrial scene of disused factories, alienated workers and a disenfranchised youth. Griffin explicitly portrays this grungy nihilistic milieu, producing photography with an ironic critical perspective on capitalism that resonated with a generation left abandoned and dispossessed. His influence on the pop music of the 1980s and early 90s is evident in the album covers he created for bands such as Depeche Mode, Echo & The Bunnymen and Iggy Pop, on display here, along with an array of portraits of icons such as Brian Eno, David Hockney, Siouxsie Sioux and Kate Bush. This show presents a broad career that was not only a reaction to a volatile era of upheaval, riots, marketisation and Thatcherism but was a crucial contribution to Britain’s changing cultural identity.

3 images

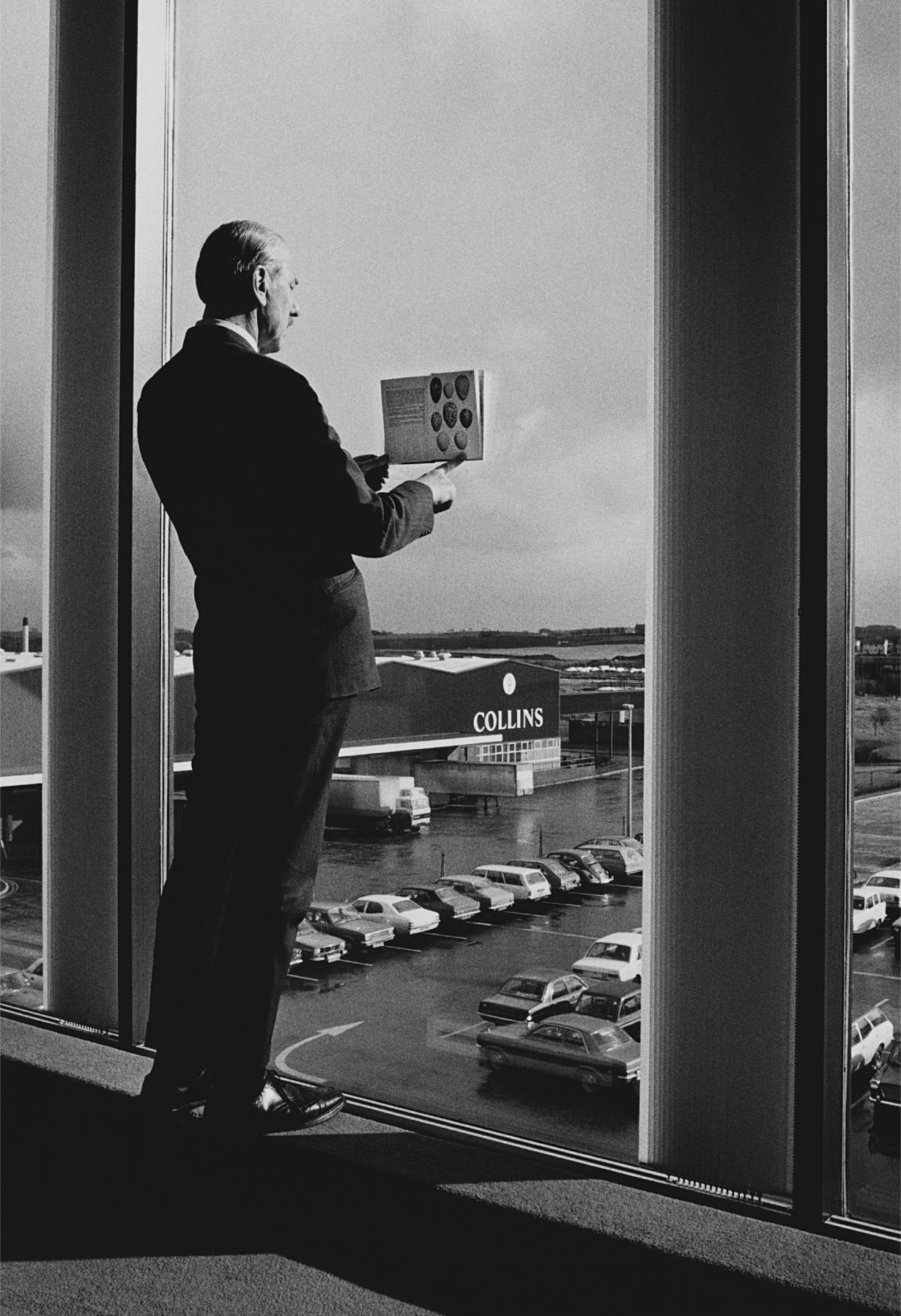

In Griffin’s images workers kiss tools, intimately involved with their labour. Steel erectors gaze out at feats of engineering with divine gnostic adulation. These are Marxist heroes stood proud on monoliths, simple, humble and indomitable. Some of these figures feature in memorable album covers, including Depeche Mode’s A Broken Frame (1982) in which a shrouded woman scythes cornfields lit by the weak glow of a coming dawn. Griffin’s work might have been lifted straight from the propaganda pages of Pravda itself, sharing in the ironic use of Soviet iconography popularised in the 80s by bands like Frankie Goes to Hollywood and the Communards. Yet these are counterposed by their ideological opposites – images of big business. Whilst manual labourers grapple with the complexities of physical reality, middle managers shuffle through shadowy boardrooms on the opposite wall. Here, things aren’t so clean cut. The lighting recedes, there’s murkiness and uncertainty in these high-rises, actions are no longer clearly interpretable – people award each other meagre trophies, struggle to embrace, conduct facile meetings. In Birds Egg Man (1976) a moody CEO gazes out from a borderless glass window, seemingly caught in a moment of existential dread. Most of these company men are halfway through some absurd or pointless act, revealed as fools, delinquents or half-wits.

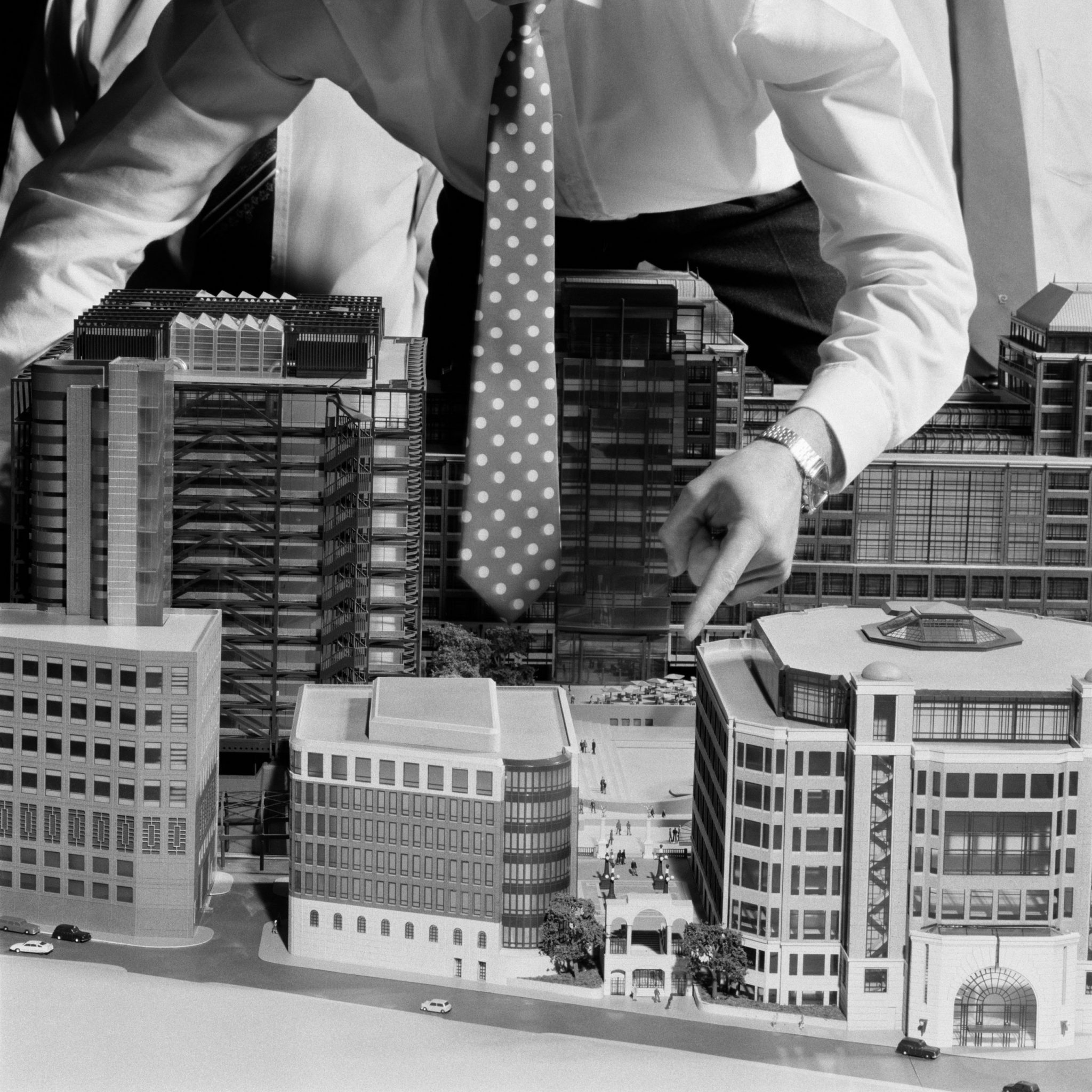

At a time when workers and work itself has been dematerialized these images are arrestingly prescient. They attempt an uncovering of relationships and negotiations around labour, class structures and communal identity. Even still, Griffin has a duplicitous relationship with reality. In the series, The Big Tie (1986), an architectural model surrounded by men in white shirts and business ties becomes a portal into the reality it portrays in miniature. One tie in dangles into the maquette, to become gargantuan, transplanted to the reality the model prototypes. The tie is a fascinatingly phallic and curiously modern codpiece, bureaucracy made manifest.

The late Mark Fisher’s book Capitalist Realism popularised the term Griffin uses in the show to describe his photographic style. Fisher frequently quoted Frederic Jameson’s line that ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism’. If Black Country Dada proves anything it’s that capitalism itself evades aestheticization; most attempts to critically respond to it tend rapidly to deteriorate, unable to keep up with its pace of change. Since the 90s, market economies have altered so drastically that these images of steel workers, coal miners and old-guard business elites have become anachronisms: heavy industry has since been replaced by the information industry; bricks-and-mortar businesses are dead or just limping by; boardrooms are transitioning into bedrooms; we’re constantly at work yet automation is everywhere. In a world rapidly detaching from material reality it’s still pleasant to ponder a past that seemed solid, even if it’s only a haunting afterimage captured on analogue film. There’s no turning back now.

Brian Griffin: Black Country Dada 1969–1990 is at QUAD, Derby 19 May – 5 September

This article is part of Remark, a new platform for art writing in the East Midlands by ArtReview in collaboration with BACKLIT. Read more here and sign up for the Remark newsletter here