How the borders between art and life beyond don’t seem to matter any more

One of the distinguishing features of the 2020 Brent Biennial was that its curators chose to foreground process-oriented art. It’s a term that’s fashionable with both curators and critics and is generally accepted to mean art that de-prioritises the object itself and privileges the process of its production. But what does that mean in practice? The foremost point of clarification would be to reflect on whose focus is being recalibrated. Does it reflect an actual shift in artists’ attention? Or are those critics and curators merely foregrounding something that has, in any case, been an integral part of artistic creation all along?

Certainly, some artists may have shown greater willingness to reveal the process of making, the unfinished business of an artwork and its social entanglements. For example, at the biennial, artist Adam Farah (who also goes by the moniker free.yard) chose to exhibit B-SIDES, a videowork made up of a string of vignettes, elements of an as-yet-to-be-completed film. Others seem to have simply deployed the term ‘art’ to describe actions that they might undertake inside other realms, a certain legibility shift that garners both financial support and the recognition that comes with institutional art commissions. Abbas Zahedi’s Brent Biennial commission for example, Soul Refresher (Mountain Rose Soda), in which bottles of soda were produced in collaboration with Square Root Soda Works – a company Zahedi used to work for – and distributed through local shops and foodbanks, suggests this kind of disciplinary frame shift, whereby ‘art’ is used to re-engage with a Brent community with whom he has previously worked as an organiser for many years. Furthermore, the tagging of artworks as ‘socially engaged’ is an example of a legibility marker that helps ‘the rest of us’ – the viewers and interpreters – access and asses the meaning and value of these actions.

Recent tumult – the pandemic and its social and political fallout – in a world that is already saturated with images and objects has meant that for many the status of a specialised subset of art images and objects has tumbled sharply. In other words, there are many who could not care less about making or seeing art objects right now, realising that they do not, cannot, love art as much as they once thought they did. It is a question of priorities. Perhaps the ‘gatekeepers leaving the gates’, as the founder of Artists’ Support Pledge, Matthew Burrows, termed the shutdown of activity within the art economy during the pandemic, has left art exposed and revealed it to be a lot less compelling than many ‘insiders’ believe it to be. The gatekeepers who controlled access to art also hid its limitations, its impotence as a force for change in the society. Now that apparent powerlessness is on view, encouraging viewers and interpreters who previously accommodated the hierarchy in the art industry to seek meaning in other aspects of artistic practice.

For ‘the rest of us’, viewers and interpreters of art in its material manifestations, becoming alert to process or responding to objects based on the processes through which they have been concretised, can provide a welcome relief from the meritocratic structure that accompanies terms like ‘well-made’ objects, ‘great’ artworks, or ‘masterpieces’ even. Yet, because biennial formats insist on making sense of things, again for the sake of legibility, ‘process-oriented’ still functions as a commoditising logic, an exchange that is wagered through language.

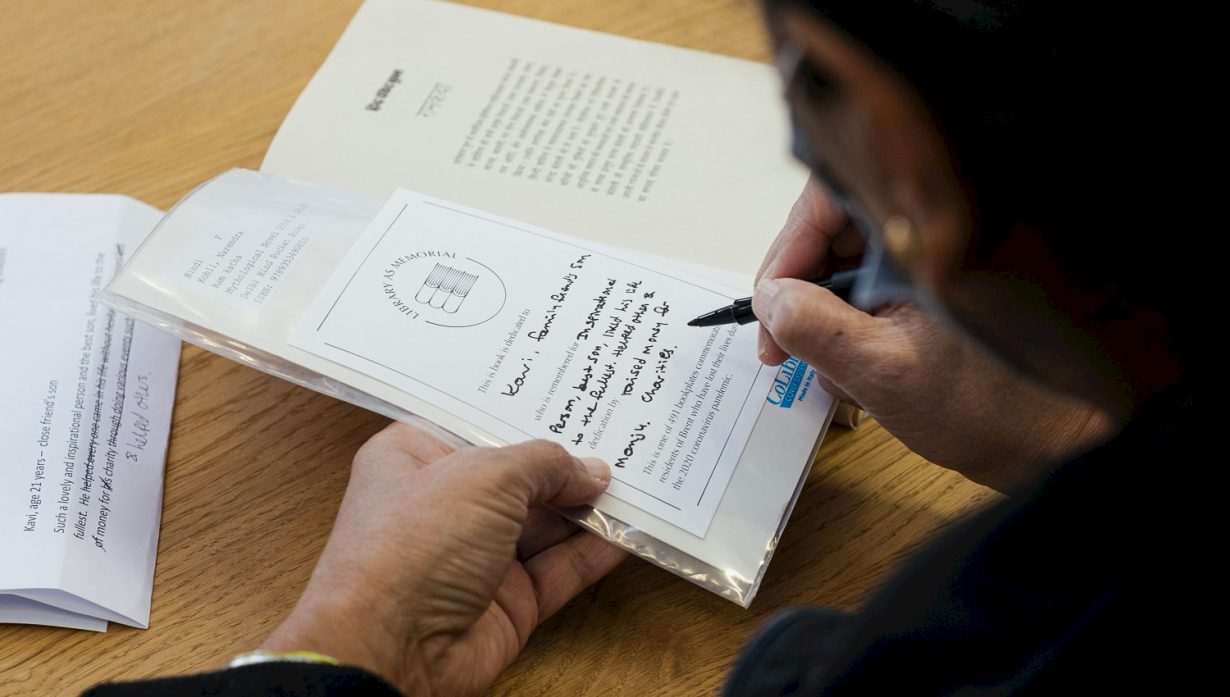

Any given process’s legibility as an artwork provides an elegant subversion for an agent who might look to other disciplines (art yes, but as in the case of projects in the biennial, ranging from Avant Gardening’s walks to Ruth Beale’s Library as Memorial, it could equally be climate justice, library science, or anything else) to further the purpose of the work when that purpose is an interdependent social transformation. For example, apart from art, a number of other intellectual, funding or employment frameworks could have been engaged to concretise and contextualise Soul Refresher (Mountain Rose Soda). Critical interpretation could begin with questioning the extent to which art (discourse/ funding) was the best host for this work to parasite.

Perhaps this next reflection speaks more to wall text or website copy. Appropriately so, for the question of how and to what extent one could refocus art away from the object itself and towards the process of its production is ultimately a question of language, interpretation and framework. And while some artists (and critics) may carry in the back of their minds the voices of yesteryear’s grumpy, bespectacled tutors insisting that one should not need to add language to the object in order to communicate meaning through art, that language remains both available and in use.

Art objects in which the processes of their production are highlighted through language do not always look dissimilar to art objects that only speak through their form. The collaborative invitation in Rasheed Araeen’s Zero to Infinity (1968–2017), an interactive sculpture featuring dozens of movable painted-wood open-framework lattice cubes, shown in numerous contexts since its first realisation in 1968 and recently installed in Willesden Library, is certainly supported, but not determined, by its material properties.

Similarly, it would be possible to present Soul Refresher (Mountain Rose Soda) as it is, without providing a framework for interpreting the bottle of drink as a work, or it would also be possible to frame the artwork by highlighting its other aspects. The copy on the Brent Biennial website leaves me wondering, for example, what the drink is made of, how it tastes and smells, what holding a bottle of it would feel like. Some of these things would have been more apparent to an IRL viewer, and indeed, the fact that the experience of consuming the drink is saved for the audience for which Zahedi intended it – the Brent community with whom he has a longstanding partnership – feels necessary and appropriate. What’s left to art is, mostly, the website image, posed and aestheticised with that blurry wash of the drink’s lurid pink colour in the foreground. Reminiscent of an advert for a tropical-flavoured drink I’ve seen pasted on billboards along Kilburn High Street, Soul Refresher treads a fine paradigmatic line between marketing object and art object. Both are commodities. This productive, mirrored porosity also structures Yasmin Nicholas’s The Children of the Sugar, snippets of the artists’ own poetry deployed in excerpts on digital billboards, bus stops and posters around the borough. Those who come across these works as physical objects – the person who encounters Nicholas’s words waiting for the number 18 bus, by chance, without the intention to go see it – need not read them as art at all. They only need to be legible as art within the small discursive framework that requires it in exchange for funding. More pleasurable still than the porosity between an art object and every other type of thing that emerges when collaborative process is prioritised over objecthood is the deflation of any false art vs life distinctions. The Brent Biennial, perhaps through its conception as an (economic) galvanisation of morale over and above artistic rarity, was necessarily built on this disposal – echoing Black, feminist and Marxist critiques of art history – of a boundary between art and life.

What emerges out of a process-oriented methodology is that these works would indeed be ‘better’ in the eyes of critical interpreters if they were to engage with them literally, or listen literally to the imperative being voiced through the work. I find this exhilarating in its unresolvable opposition to what art has meant at its (discursive, economic) core: coolly proposed rhetorical ideas or rehearsals of action, representation of what action might speculatively look like. Process-oriented practice, like Barby Asante’s Declaration of Independence, a performance the artist describes as an ongoing forum ‘to share stories and experiences in relation to the legacies of slavery and colonialism’, is of course ‘ongoing’ because the artwork is the process of the work, not a representation of what it could look like. And of course, those legacies are forever.

To reframe what one of Asante’s collaborators, Marxist, feminist and anti-imperialist psychoanalyst Gail Lewis, wrote elsewhere, ‘[understand] that colonialism transcends, even in neo-colonial times, apparently, formal independence’. To read that in the context of representation and form is to access what is useful about Asante’s project. As a representation of the idea of independence, of womxn’s liberation, Asante’s Declaration of Independence does not voice what womxn and other art viewers have not already heard before, rhetorically. Indeed, the ‘formal’ qualities of independence are familiar to many (and in fact were incisively co-opted by the Leave campaign in the run-up to Britain’s referendum on EU membership). The transformative energy of this artwork, then, is in its breaking of the fourth wall of the ontology of the art object and making a literal invitation, from Asante to you, yes you, to free yourself from any number of constraints. Why not? The gatekeepers have left the gates, after all.

Refocusing our critical lenses towards process-oriented practice supports the potential of an artist or an artwork to enact ‘political, social and cultural transformation’ that fills funding applications and public-art copy. An art viewer who does not participate either through a sort of flaneuresque grazing that professionalised audiences are accustomed to, or through intellectualised ideas of critical distance, is ill-suited for this paradigm. It’s a shift which I imagine drives those who are repulsed by participation to scurry out of the performance room. Without gatekeepers or spectators, who knows what our creative ecosystem could look like? To find out, we would just have to do it.