At a moment when the artworld is hyper-interested in ecological exhibitions of fungi and bacteria, Lin’s human and vegetal encounters evidence a deep fascination with how the historical can bleed into the contemporary moment

During the Black Plague there were Dutch pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela who were in the habit of wearing pewter badges featuring anthropomorphic vulvas and penises, often depicted riding horses and bearing sceptres. They believed that such charms would ward off disease and disaster. Now, these apotropaic genitals serve as inspiration for American artist Candice Lin’s recent phallic and vulvic installation for the Arnaldo Pomodoro Sculpture Prize at GAM – Galleria d’Arte Moderna, in Milan.

That work combines painted faux-marble columns, textile chinoiserie, chastity belts and glory holes in an elaborate, ritualistic unveiling of Lin’s own reimagined plague talismans. The exhibition is a consummation of Lin’s approach, a commitment to studying material histories married to her sense of humour, which is essential to her practice. Contrary to the classical ideal of the image liberated by the master sculptor from the marble block, Lin reveals the stories embedded in the material itself. “The work is at its best when I let the materials lead,” she tells me. Here in Lin’s hands, metal, silk and scagliola become more than medium; they become illuminated histories of their use, their origins and their movements across time and cultures.

Lin’s future relics – her work consists of sculpture, drawing and video, objects ranging from her own indigo-bound pandemic diary of isolation and observation, to a medieval trebuchet flinging lard laced with bone char, to a screen riddled with pestilent chatbot popup messages – bear temporal signifiers that are scrambled and remixed, suggesting that history and its actors are neither linear nor stable. For example, her near-prophetic 2020 exhibition Pigs and Poison, which toured to venues in New Zealand, China and the UK, was conceived of before the COVID-19 pandemic, and her 2021 exhibition Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping at the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis, was developed during its early peak. Both exhibitions wield hybrid human/animal images and corporeal sensations to untangle racialised notions of virality and disease. While not a direct response to current events, Lin’s work calls attention to a troubling history of racist conflations of Asian bodies and infection, which seems to continue to draw ever closer. Lin’s work evidences a deep fascination with how the historical can bleed into the contemporary moment, coalescing into a single, cyclical historical timeline in which the events of history recur and fold in on themselves.

Lin has since drawn out even more connections through her extensive research practice, mapping an expansive ecology of colonialism, and in doing so also proved her prowess as an alchemist and historian of materials. Like the process of fermentation itself, Lin feeds the seeds of her initial fascinations with raw material until it blooms into a potent visual metaphor for colonialism’s web of commodities and the violence of those productions. The tendrils of this colonial web knot and coil together, for example, in the indigo feline tent in Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping, which began with Lin’s research on indigo as medicine, indigo poisonings on British colonial plantations in India and changes in traditional Nigerian indigo adire eleko cloth during British colonial occupation. These intertwined histories materialised as Lin herself carried out the traditional process of fermenting indigo, pressing, stirring and feeding it, placing her own body within that ecology.

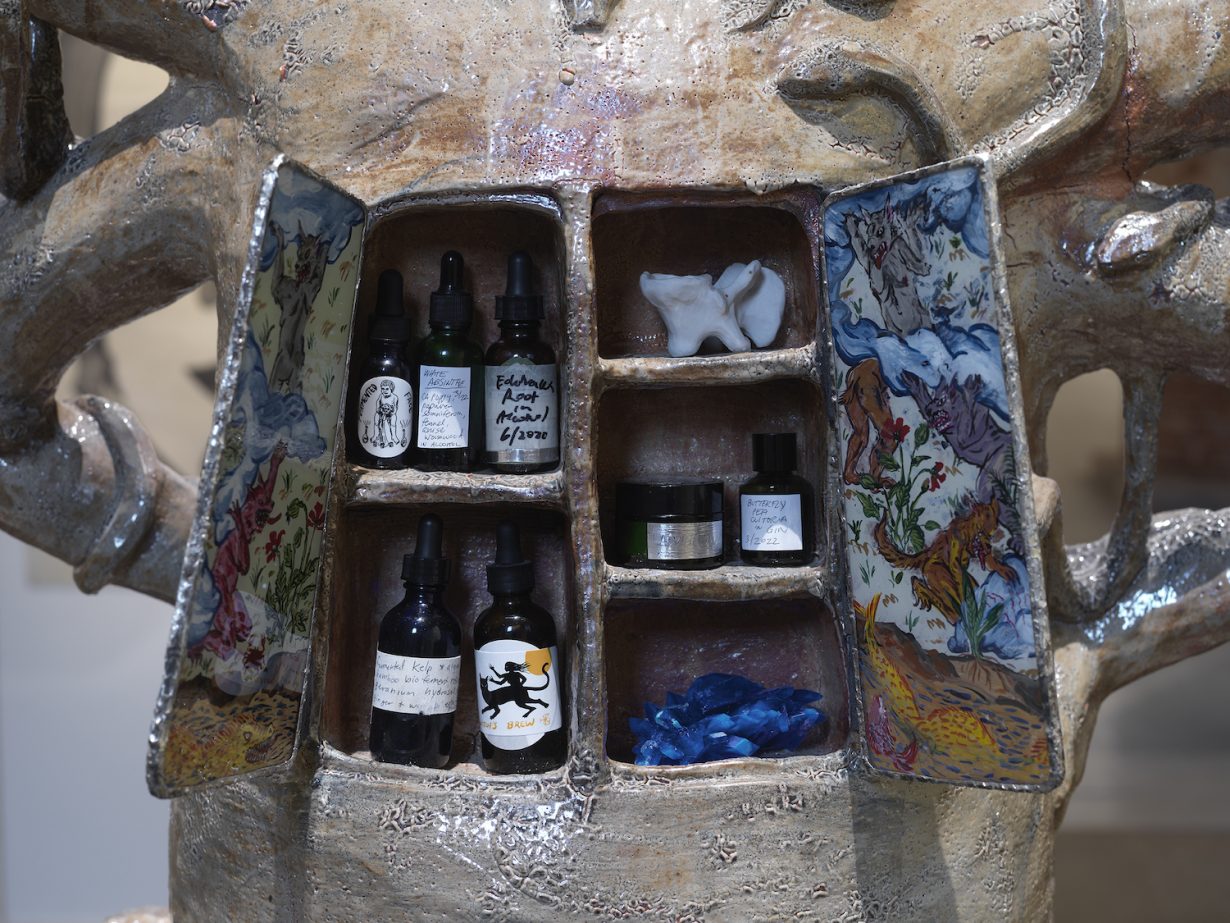

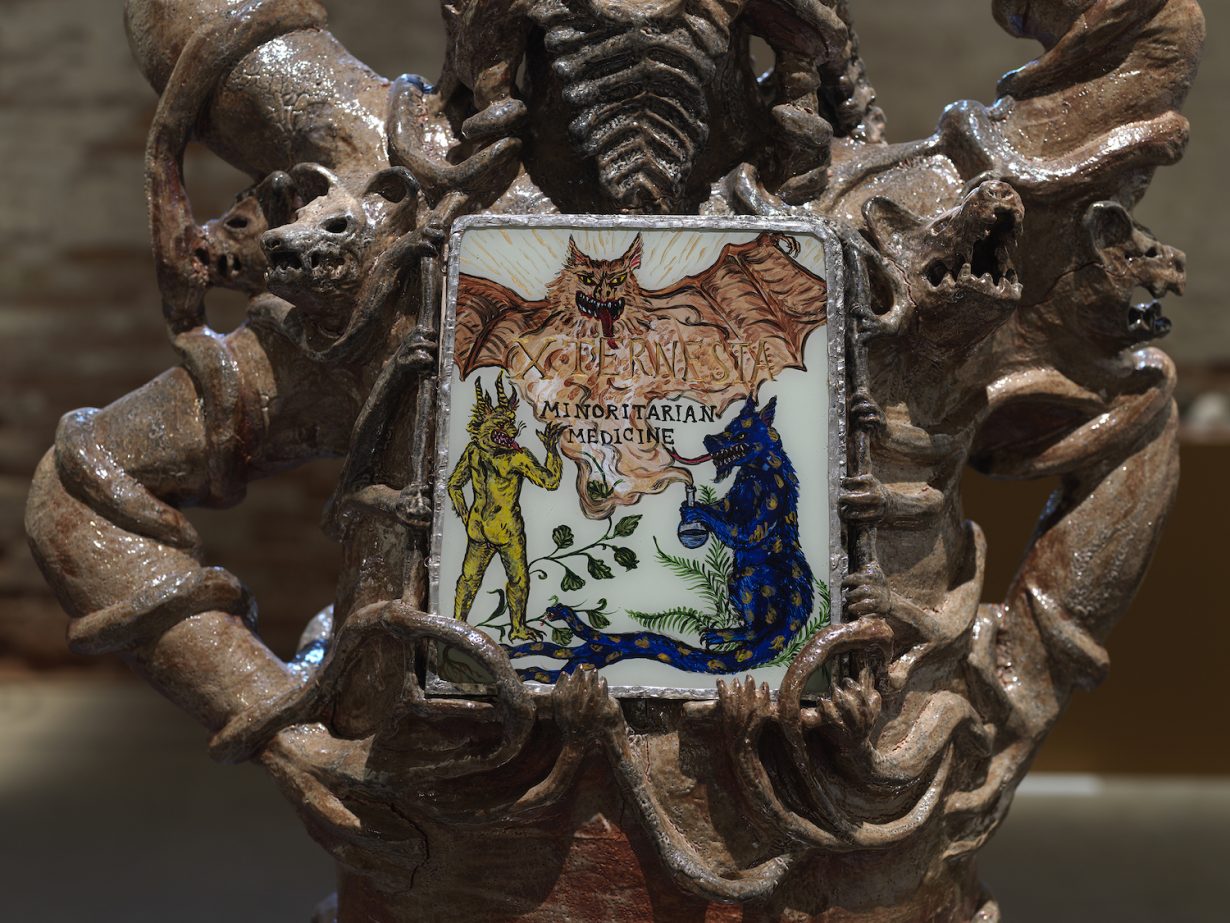

Human and vegetal encounters that take place between poison and remedy reemerge in her recent Venice Biennale installation, Xternesta (2022), in which demonic ceramic totems studded with niches interring various potions and serums act as a botanical library and DIY medicine cabinet. ‘Tincture drawings’, in which the artist makes drawings under the influence of her own dizzying concoctions of sugarcane, tobacco and indigo, act as companion records to the demonic archive, offering a kind of surrealist, automatic document of the porosity of the mind. However, the vegetal matter in the drawings themselves acts against and resists the memory of the archive, as the ink made by Lin, of oak gall and rusty iron-water, burns through the paper and often leaves ghost images. Lin’s work centres this instability and the hauntedness of the archive, describing her work, when we talk, as a visioning of “the cloudy shape of the archive, temporarily felt”.

Accompanying the drawings, recipes for alternative medicines – such as abortifacients and ‘clairvoyant testosterone’ – are contained in a handpainted glass book inscribed with the title ‘minoritarian medicine’. A reference to the capacity of plants to produce both remedies and poisons, Lin draws our attention to how such preparations were used by the resistance in the Haitian Revolution, as well as in uprisings of indentured Chinese labourers in the Caribbean. Indeed, through these human and nonhuman material connections as sketched by Lin, surface historical solidarities between people too. For example, on the handpainted glass tabletop adjacent to the book, ceramic amphibians have been forged from clay from the swamps of Saint Malo, Louisiana, a historically multiracial Filipino, Indigenous and Maroon community and the first Asian settlement in the United States. But as the swamplands of Saint Malo literally recede, the mineral record of this community slips away, a fact that is calcified within the frog vessels that are pried open for dissection on the glass tableau before us.

As Lin has further turned to crafting mythologies to expand the worlds of her objects, her bigger story about colonial realities and speculations, fantastic characters and plots often teeter at the edge of fiction, emphasising moments of history’s absurdity and the instability of identity. For example, a figure who appears in her work is the eighteenth-century European George Psalmanazar, who claimed to be a native of Formosa (present-day Taiwan) and performed his idea of ‘Asianness’ by smoking opium and speaking a language of his own invention. The form of Lin’s demon guardians featured in Xternesta come from sketches of a devil idol made by Psalmanazar in his fabricated ethnographic work; the title of the installation comes from the name he gave to Formosa’s make-believe capital city.

Never utopic, Lin’s speculative storytelling is bolstered by her knack for worldbuilding through uncanny objects and multisensorial environments. The sheer number of techniques she uses – weaving, ceramics, dyeing, painting, animation, alongside natural processes like fermentation, sporing, pissing – constructs an immersive space. Lin’s previous engagement with Saint Malo’s history, Swamp Fat (2021), included in Prospect 5 in New Orleans in 2021–22, uses a process called enfleurage to infuse lard with a blend of ‘demonic’ corporeal smells, like shrimp and decaying flesh. Visitors were invited to take this scent with them by rubbing the lard on their skin, a pseudoscientific practice of the Middle Ages meant to ward off disease, and an implicating, sensual act beyond mere observation. Other bodily affective states are productive too, in addition to nausea or grief, as the viewers in Lin’s world are also offered moments of respite and intimacy. In Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping, the central indigo shelter comprised of delicate wearables, painted rugs and ceramic cat pillows offer us a space to metabolise the vast geographic matrix of colonial encounters in which we find ourselves imbricated.

At a moment where the artworld is hyper-interested in ecological exhibitions of fungi and bacteria, there is a risk that we might simply, as Lin puts it, “get lost in the visual enjoyment of unstable materials”. Lin’s 2020 show of small paintings, Roger and Friends, at Friends Indeed, in San Francisco, evidences that even when the artist steps back, if for a moment, from her role as storyteller to focus and reflect on the conditions of her own inner world, she is still actively theorising an ecological encounter with ‘the other’. Cats, which appear often in Lin’s work, embody a compelling sense of whimsy, familiarity and curiosity to which we might affix our ideas about relationships between humans and nonhumans. Lin’s portraits of her cat Roger suggest that Donna Haraway’s now-almost canonical The Companion Species Manifesto (2003) might be differently read if it were centred around our interspecies bond with cats rather than dogs. In Bedroom Licks (2020), Roger seems to recoil from an overaffectionate human tongue, while in At the Death Bed (2020), Roger is seen lovingly observing people in a moment of profound loss. In Lin’s paintings is an awareness that to love the nonhuman other is to revel in our mutual opacities, and to delight in the glimpses we get of one another, no matter how brief, without demanding more.

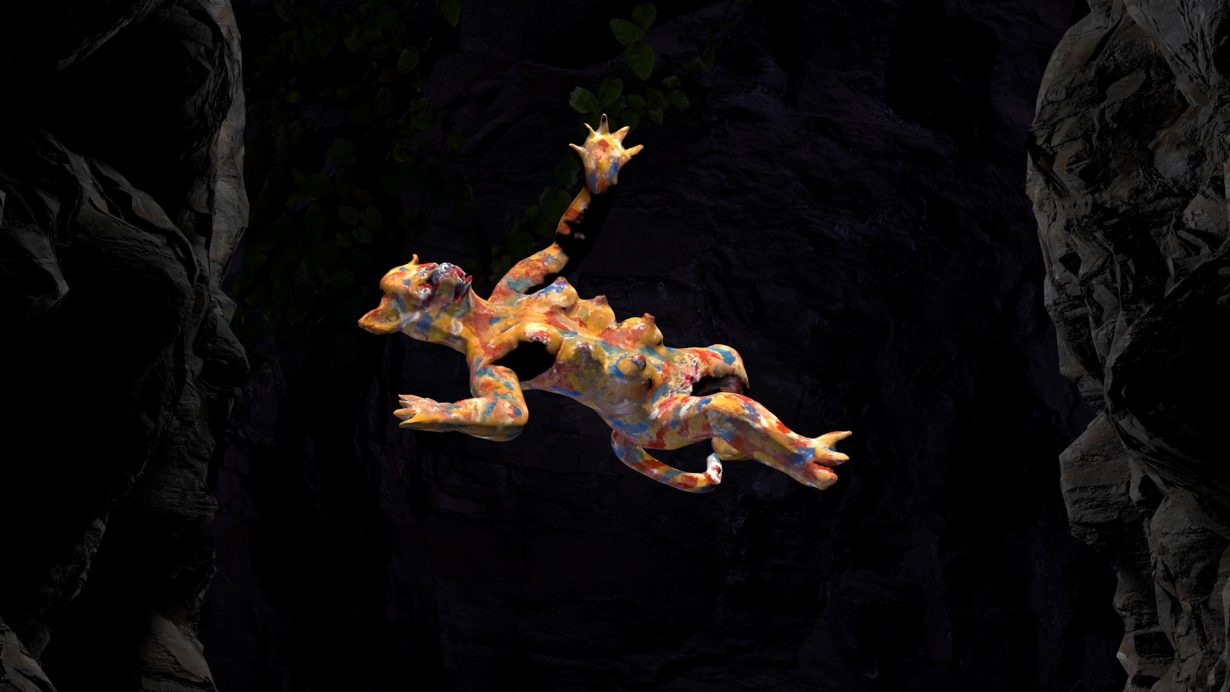

In Lin’s most recent work, Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory (2023), made for the Gwangju Biennale, visual and narrative phantasmagoria emphasises rather than obscures real-life social, material and environmental histories. Flanked by workstations and ceramic onggi vessels (microporous containers often used for fermentations), a TV screen is inlaid into a glazed ceramic frame: in the video a hybrid cat-pig-human demon awakes from a slumber with a feverish desire to have sex. Though the demon doesn’t understand the nature of this yearning, the feeling leads our demon friend on a kind of perverse hero’s journey to find their lover through time, memory, menstrual blood and shit. In the story’s final act, faced with its own oblivion by exorcism, and while under the influence of lithium, the sex demon catches a glimpse of his lover, who, finally, recognises him back.

This story of bodily desire in the spiritual world is a culmination of Lin’s earthly research. I learned from Lin that the lithium-addled sex demon represents a personification of a phenomenon documented by anthropologist Aihwa Ong in Asian women working with multinational electronics factories who would become seized by demonic possession on the factory floor. For Lin, who first learned about these histories from the artists Ann Haeyoung and Miljohn Ruperto (who have also made work on the subject), these mythological objects, queer epics of desire encased in sensorial environments, were sparked by an initial curiosity in the studio about lithium ceramic glazes, leading her on her own fantastical journey. To meander through these worlds with Lin is to leave with a better understanding of the threads connecting us to each other. “I make art to learn,” she tells me. Though she makes a good teacher, too.

Candice Lin’s Arnaldo Pomodoro Sculpture Prize exhibition is on view at GAM – Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan, 14 April – 18 June