Cat Kron tours the last of the summer exhibitions in Denmark, Norway and Sweden

Copenhagen in the summer is for swimmers. I’d mentally blocked the glowing accounts I’d read of Danish waters, assuming those extolling its virtues were of a hardier constitution. But the sea water that cleaves the city is temperate and astonishingly clean, and I needed it after attempting to walk across town to 1 Gallery in Copenhagen’s Meatpacking District. The Meatpacking District, a still semi-industrial expanse of warehouses near the waterfront, is one of the few stretches in this historic, green-bowered city that, on a hot day, rivals in blinding exposure the cement expanses of newer, more hastily built and less elegantly planned urban centres. Copenhagen’s galleries were mostly packing up summer group shows or shuttered in preparation for late August’s Art Week; I was grateful to find V1’s cool, naturally lit gallery open, and a solo show by the New-York-based painter Grace Metzler still up. Metzler’s faux-naïf paintings alternate between swathes of abstract pastels and distinctly articulated barrel-chested figures with limbs that snake and snarl around potato heads. These figures, who roam through domestic interiors and bucolic landscapes, are accompanied by narrative titles that manage to be both wry and tender. In Doing what we can to help Dad feel like a kid again (2022), an older male in shorts kicks his legs out as smaller figures extend a jump rope for him. Charmed and somewhat refreshed but still flushed from heat, I stumbled towards the harbour baths to be fully restored.

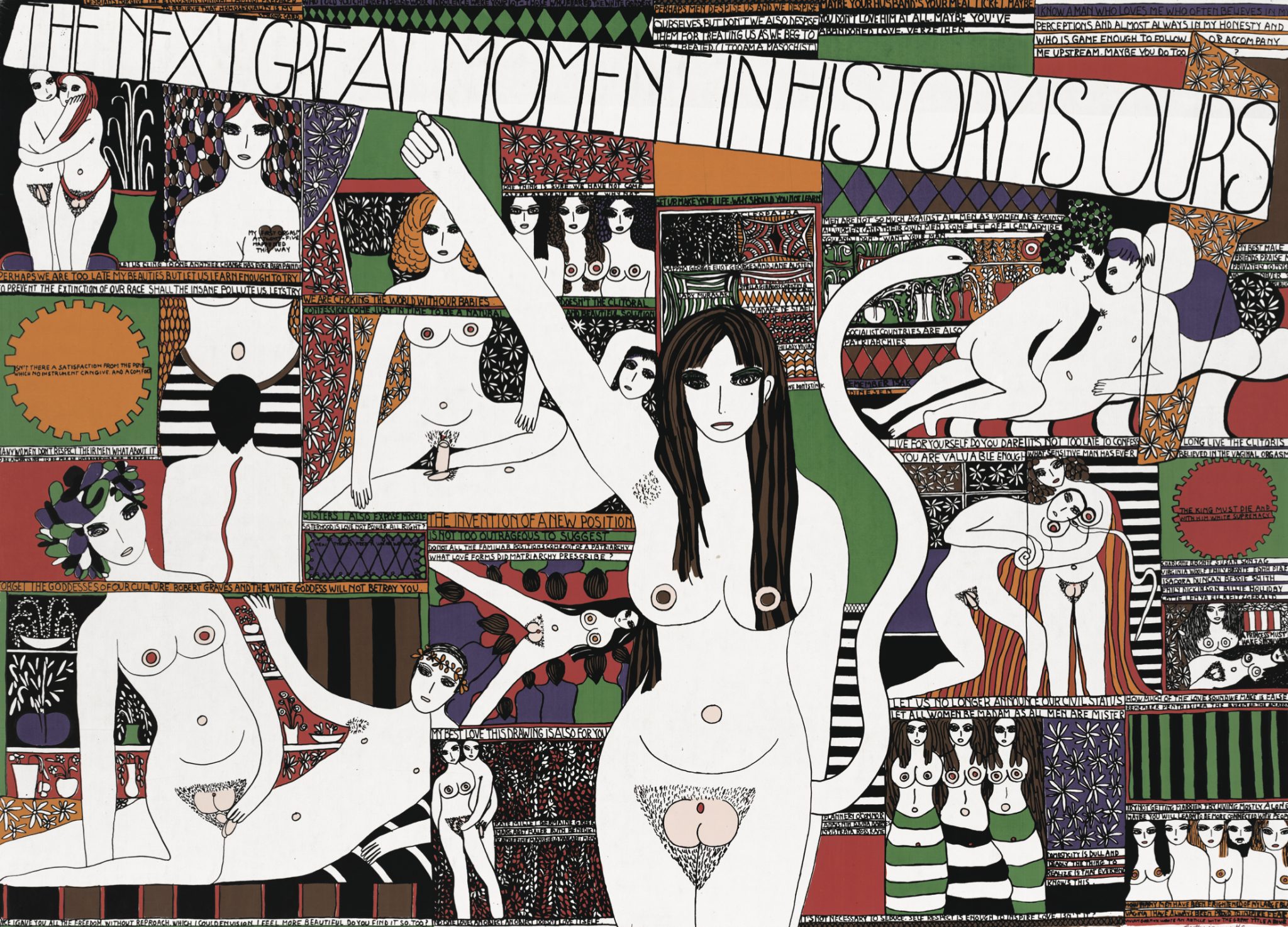

An exemplar of Danish Modernist architecture and a mecca for modern and contemporary art for half a century, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art sits on Nivå Bay, facing Sweden, a half-hour north of Copenhagen. (You can swim here too, in the water visible just past the museum’s grounds.) I caught the tail end of the Dorothy Iannone exhibition, which maps the artist’s practice across six decades. The museum takes a variety of approaches to the challenge of the visual density of her work – mounting diaristic plates serially and reproducing spreads from sketchbooks as floor-to-ceiling wall dividers. The artist recounts periods of her life like erotic fairytales, chronicling her tumultuous relationships with lovers including artist Dieter Roth in An Icelandic Saga, a series of panels (from 1978, 1983 and 1986) whose magical-realist descriptions are undercut by frank admissions of Iannone’s own all-too-human struggles. An enlarged page from A Cookbook (1969) whose hand lettering could have been lifted from

1970s vegetarian dietary touchstone Moosewood Cookbook, features the following text, overlaid in all caps on a recipe that appears to be for creamed endive: ‘i had poisoned myself with tomato sauce infected with aluminum. i sadly sat on the toilet, expecting to die within 45 or 50 minutes, and studied my german.’ The text concludes, ‘i hope i live long enough to ____ what?’ In a 2016 interview with Maurizio Cattelan for Flash Art, the artist described her life and work as driven by a longing for ‘ecstatic unity’. And gathered here, her oeuvre registers as no less admirable for the periodic heartbreaks and other personal and professional setbacks of their author.

On the far eastern edge of the Scandinavian Peninsula, the equally architecturally striking Bildmuseet was erected in 2012 on the Umeälven River, where it spills out into the Baltic Sea. Designed by the Danish firm Hanning Larsen, the spare, Siberian larch-panelled building is nestled into the university complex of Umeå, a college town in Sweden’s northernmost region and a hub of medical research, where the Nobel Prize-winning CRISPR gene-editing technology was developed. The institution’s mission statement is to showcase the intersection of art and science, a mandate in keeping with the generative principle behind the work of Nancy Holt, whose retrospective it organised over the course of the past several years while weathering the global pandemic. Holt’s exploration into responsive design is encapsulated by her ‘Systems Works’, of which several ventilators from the series Ventilation System (1985–92) were on view. In her catalogue introduction, Lisa Le Feuvre, executive director of Holt/Smithson Foundation, writes, ‘Although largely assumed to be preoccupied with landscapes and the celestial realm, Holt was equally interested in manifestations and interpretations of architecture’, and the ventilators were envisioned as interior/exterior installations to highlight the bowels of tubing that course invisibly through the infrastructures of large buildings. They’re typical of Holt’s work, which in contrast to much of her Land-art peers is not only attuned to place as one finds it, but committed to working dynamically with its idiosyncrasies and specificities – extending in this case to the very air coursing through the building. This flexibility, exhibited during her lifetime, is evidenced by the works’ plans, which were designed such that the museum and foundation could in good faith present new iterations even eight years after her death. It was, however, no small task. In recreating the structures, the curators and Le Feuvre had to triangulate between archival blueprints and the specs of the museum to design a reiteration respectful of both the project and Bildmuseet’s sanctum-like architecture.

My companion had booked a cabin on a pleasure cruise from Oslo to Copenhagen before our flight, and we needed to make it back to the west coast of the peninsula to meet our vessel. A Norwegian friend we explained this to was incredulous. Cruises in Scandinavia are, it turns out, regarded by locals much as they are everywhere else. (Personally, I say ignore the cynics.) Just as the region is a hub for artists spanning the globe, it’s been heartening on trips made over the past five years to witness how artists within Scandinavia are supported and championed. We arrived the night before departure in time for the opening of Norwegian-born Gardar Eide Einarsson’s solo show at Standard (Oslo). The show bears the title Maybe It’s the Calm Before the Storm, Could Be the Calm, the Calm Before the Storm, quoting then-President Trump’s uncharacteristically lyrical comment made, seemingly apropos of nothing, to military leaders at a 2017 photo op. In one gallery, white-painted bricks are strewn across an otherwise bare floor. They’re arranged like tiny, rudimentary monuments, two bricks upright like bookends, with another resting on top, an arrangement used by pro-democracy protesters to slow the advancements of military vehicles during the 2019–20 demonstrations in Hong Kong. While the former US leader’s commentary seemed calculated for impact without a clear referent or intent, Einarsson’s referent was as explicit as his aim was unclear. What are we to make of these visual extrapolations of protest, however much we agree with the cause from which they have been taken? Ultimately however, that this exhibition felt unresolved was of less import than its maker’s conviction, and it was heartening to see work that challenges rather than answers given space.