The artist paints his home country with a tender familiarity that undercuts the sexualised, colonial visions of life in the equatorial tropics that have often dominated art history

The best art is often the product of knowledge and happenstance. This is the case in Che Lovelace’s exhibition of ten paintings depicting scenes from his home country of Trinidad. His subject matter recalls the same elegant bodies found in compatriot Boscoe Holder’s portraits of the island’s workers, musicians and playboys; the lush, fervid landscapes of Peter Doig’s canvases. Yet Lovelace’s style, a trippy combination of cubist angles and realism, outstrips them. In The Breath (2022) a muscular young man lies on his back in swimming trunks. It’s as if the viewer is looking at the subject with their head rested on his thighs, his groin dominating the bottom right of the frame, a nod to sexualised, colonial visions of life in the equatorial tropics (think Charles Warren Stoddard’s thirsty writing on island life or a homoeroticised Paul Gauguin), but with the fetishistic tension undercut by the sleepy psychedelia of a night sky. With a hand resting on his chest, the man’s dreams are constructed of acrylic splashes of yellow, deep blue, turquoise and a near-fluorescent orange that spill across the almost-metre-and-half canvas.

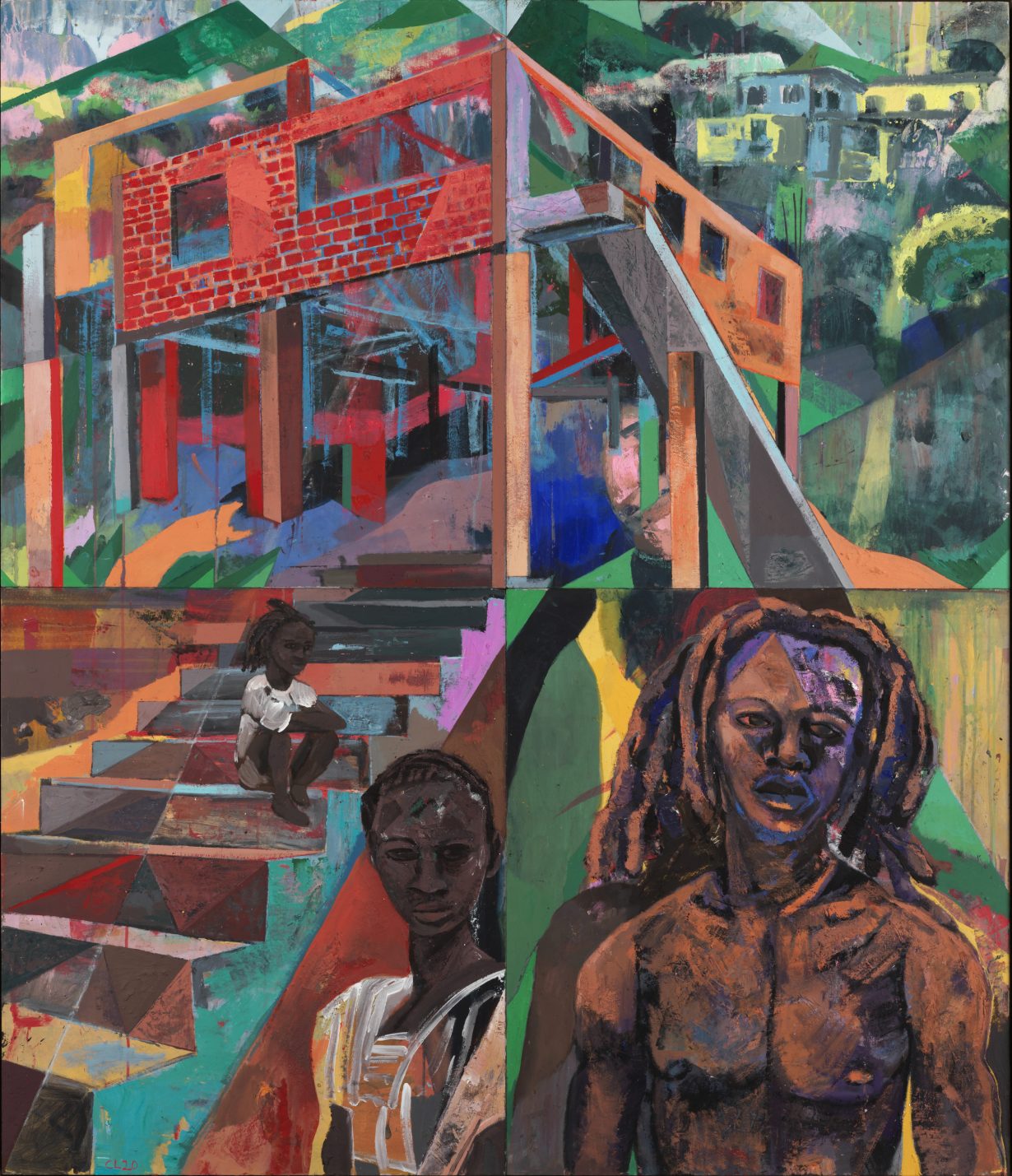

All of Lovelace’s paintings are made on a grid of four compressed-paper board panels (material intended for book binding), an innovation born of necessity since canvas was expensive and tricky to obtain in Trinidad when Lovelace started painting during the mid-1990s. That the overlapping imagery often doesn’t join up perfectly when the panels are assembled adds to the sense of discombobulation: in Street Dance (2016–22) a frantic carnival scene plays out against a busy semiabstract, geometric townscape. While coming together as part of the whole, each board boasts its own individual palette; something pushed even further in Moonlight Searchers (2022), in which two naked women pick through the undergrowth, the scale shifting across the quadrant; or The Red House (2021), in which each board could just as well be shown independently (showing, clockwise from top left, a red brick house; a hilltop of colourful homes; a topless man with dreads; a young mother, her child sat on a small flight of steps nearby), but which together play out a miniature drama for the viewer (are we witness to an argument or a flirtation?). These formal ploys deconstruct any reductive, one-dimensional view of Lovelace’s home, embodying, both in technique and subject, the many stories and textures of modern Trinidad.

Day Always Comes at Corvi-Mora, London, through 17 June