Remembering the Iranian film director Dariush Mehrjui

When Iranian director Dariush Mehrjui was killed in his home on 14 October 2023 in a still unexplained act of violence, the artistic community in Iran mourned him as one of their cinema’s founding fathers, credited with establishing film as the country’s most important cultural export in recent decades.

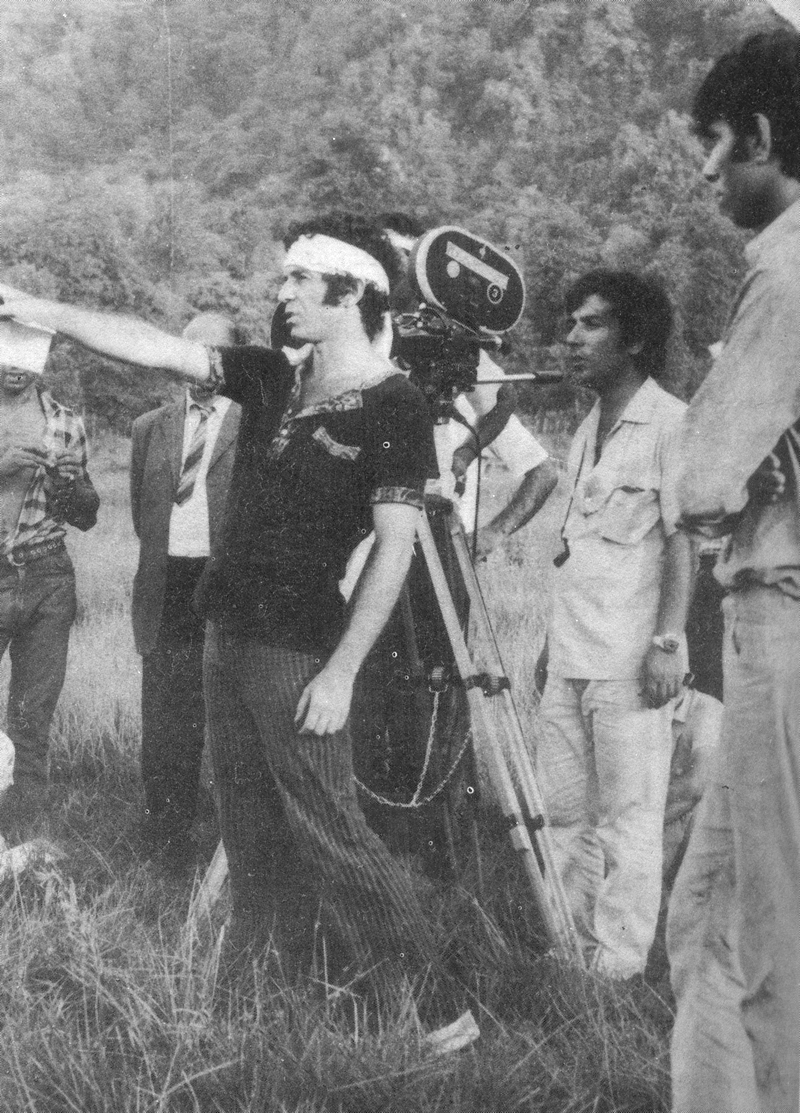

When Mehrjui began his cinematic career in the 1960s, Iranian film was dominated by Filmfarsi, often frivolous, plot-driven, all-dancing and all-singing films. Mehrjui, a 28-year-old UCLA philosophy graduate, released The Cow in 1969, and the New Wave in Iranian cinema began in earnest, drawing upon Iran’s centuries-old poetic tradition for its syntax and its philosophical and humanistic heritage for its subject matter. Mehrjui’s talent was, as described by his first wife, architect Faryar Javaherian in the documentary Mehrjui: The Forty Year Report (2016), ‘moving against the main currents of societal thought’.

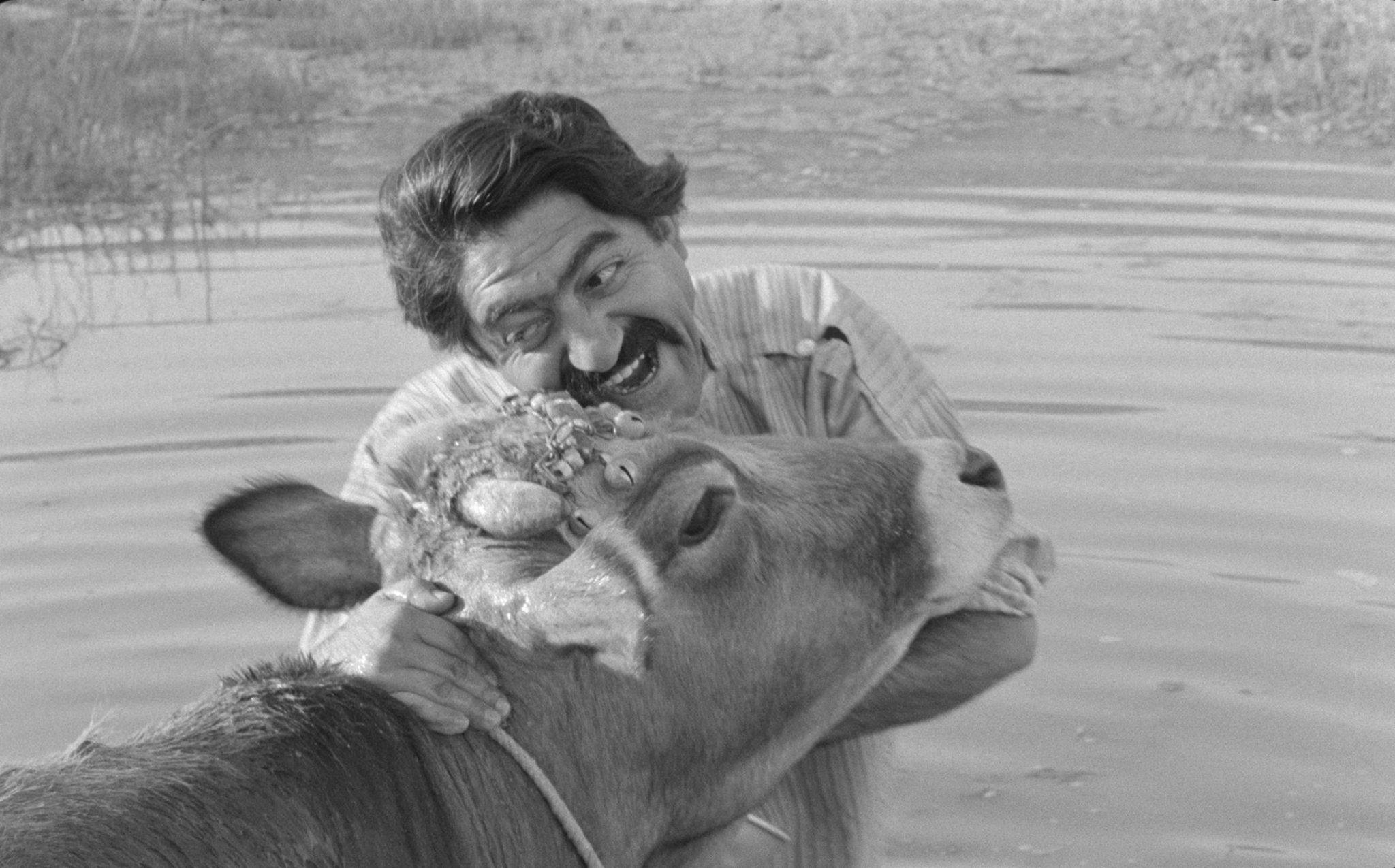

Adapted by Gholam-Hossein Saedi from his play and novel of the same name, The Cow depicted a villager who, despairing the death of his cow, begins to believe himself to be his beloved animal companion. The film is a product of the political turbulence of the 1960s: film critic Jamsheed Akrami has contextualised the film within Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s modernisation project that threatened the social fabric in impoverished rural areas. However, to read The Cow in the context of state politics only is to profoundly misunderstand Mehrjui’s artistic vision. The film discusses themes of global significance such as the collision with modernity, the fear of the other and the simultaneously suffocating and nourishing nature of community; Mehrjui was always adamant that his work was in dialogue with existentialism, absurdism and the search of meaning, and that his discussion of the local context should inspire discussion of larger themes. Mehrjui’s philosophical approach to the political turbulence that has rocked modern Iran provided a blueprint for generations of filmmakers to come, ensuring the cinematic medium would both push the boundaries of the state-sanctioned narrative without being accused of overt affiliation to party politics.

Mehrjui continued to work closely with Saedi after The Cow, collaborating again on the 1978 drama The Cycle. Saedi and Mehrjui soon became emblematic of the differing paths that Iranian writers and filmmakers would take: while Saedi was a crucial member of the Committed Literature movement that drew inspiration from Marxism and derided art that prioritised form over content for being a bourgeois game of aesthetics, Mehrjui never fell into the trap of writing political manifestos that only incidentally used film as their medium. Even as Saedi was arrested 14 times in the 1970s for his political activity and was tortured during filming of The Cycle, Mehrjui remained embedded in a cinema that refused to consider the essential unit of Iranian society by their political affiliation but rather by their humanity.

A leitmotif of Mehrjui’s 50-year oeuvre is what Richard Gabri has coined ‘intersubjective vision’ in The Cow, whereby the protagonist’s and the viewer’s vision becomes one, forcing the viewer to consider narratives other than those officially sanctioned. Ironically, by drawing on a humanism that expanded his audience’s perspectives and allowed them to see clearly what was otherwise obscured by familiarity, Mehrjui’s early films proved subversive to totalitarian regimes that sought to control meaning. However, when The Cow – smuggled to the 1971 Venice Film Festival and screened without subtitles – won the FIPRESCI prize, the first international award granted to an Iranian film, the Shah, and the Islamic regime after him, were too hesitant to stymie the international recognition Iran’s cinema was garnering. This did not prevent Mehrjui’s films from being afflicted by censorship and Mehrjui struggled to obtain permits to shoot his films throughout his career. A self-avowed elitist, he often complained in interviews that government officials assessing his films had low IQ and were so poorly educated that they simply could not understand his work. But he persisted, continuing to film, and at the time of his death was working on a new production.

Though the vast majority of Mehrjui’s films were made after the 1979 Islamic revolution, critics such as Hamid Dabashi have claimed that Mehrjui died artistically after Saedi succumbed to addiction and depression in exile in 1985. Mehrjui’s art did fundamentally change in the Islamic republic. He admitted that after the revolution he lost interest in the life of the working class because he argued (perhaps somewhat superficially) that the revolution had brought the working class to power by elevating the previously downtrodden clergy to a position to power. Instead, he turned his gaze toward who he considered the most vulnerable in Iranian society – namely, women – and dedicated himself to a series of films centring female protagonists: The Lady (1992), Sara (1993), Pari (1995) and Leila (1997). Mehrjui never quite achieved the same success he experienced with The Cow; internationally, these films did not, as film critic Godfrey Cheshire argued, meet Western audiences’ appetite for Iranian cinema that provided a ‘certain distanced exoticism’ rather than a ‘sleek, educated, post-modern Tehran’. Domestic film critics were also unconvinced; Houshang Golmakani found the characters unbelievable, and Hamid Reza Sadr argued Mehrjui’s depictions of women, no matter how pivotal they are to the plot, were evident of a deep-seated misogyny which Sadr recognised in the works of other pre-revolution Iranian filmmakers. Still, the cult classic status of Mehrjui’s post-revolution films launched the careers of a generation of women actors such as Leila Hatami, Niki Karimi and Golshifteh Farahani, whose performances redirected Iranian cinema’s gaze to the domestic sphere which has since become the primary dramatic locus of Iranian film, including in director Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-winning A Separation (2011).

Mehrjui eventually became a victim of his own success. With the influence accrued from founding a cinematic movement also came the suffocation of public expectation: while he was lambasted for not having done more to support the opposition to the regime, Mehrjui considered himself a victim in equal measure – his shoots were frequently held up by the regime’s bureaucracy and films centring women’s struggles such as The Lady werepermanently banned in Iran. Most likely, his death will too be subsumed by similar debates. The speculation, no doubt distressing for his family, is also at odds with his artistic vision. Mehrjui reiterated throughout his career that cinema, like poetry, ‘cannot take sides’. It would be ironic for his legacy to be consumed by the division his life’s work contested.

Tiara Sahar Ataii is an aid worker and writer, interested in policy, the Middle East, and Iranian cinema. She was included in the Forbes 30 under 30 list.