The founder of the digital art platform that took over Piccadilly Lights and Times Square during the pandemic, talks about creating a different artworld

Based in London and one of a number of new art initiatives that developed during the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns that accompanied it, CIRCA is a platform, founded in 2020 by Josef O’Connor, that showcases digital art, both online and on advertising screens in London’s Piccadilly Circus, and has since expanded to incorporate screens in Seoul, Tokyo, Milan, Los Angeles and New York. The advertising on the screens is paused for three minutes every day, when the screens become a ‘digital canvas’ for artists’ work.

CIRCA commissions monthly, and each participating artist also produces a print edition, limited either by number or by time. A portion of the proceeds from sales of these editions are ‘recycled’ as cash grants to artists and to fund future commissions. Sales from the prints have in the past also supported London’s nonprofit institutions such as Chisenhale Gallery and The Showroom, as well as funding CIRCA and Dazed’s Class of 2021, a global initiative that invites 30 artists to show their work in Piccadilly and win a cash prize of £30,000. #CIRCAECONOMY funds are also distributed as direct-to-community or ‘direct to creative’ grants. The name CIRCA alludes to the fact that artists are invited to create a response to the world ‘circa now’.

ArtReview How did CIRCA come about?

Josef O’Connor CIRCA was the product of lots of past journeys and skills that I picked up. I can make films, edit, write presentations and go into a boardroom, which helped in bringing this project to life. I had been thinking about doing something in this space since I was nineteen, but back then Piccadilly was a mosaic of different screens, and it’s only recently been turned into one single canvas. I suppose it was just a matter of time until someone came up with the idea.

AR And in a sense CIRCA became a reality because of the pandemic and the lockdowns associated with it…

JO’C Yes. When lockdown first hit, I was between homes, feeling really unsettled and just working off my laptop. Like everyone else, I thought everything was going to fall apart. But then there was a moment when I realised that this might actually present the opportunity to make CIRCA happen. Lockdown created cracks in the foundations of what existed. Everything stopped. Everything paused. Footfall fell and advertising spend became less justifiable. In some ways it created a magical moment that allowed for new ideas and new possibilities to emerge. People to whom I was reaching out, emailing and contacting were suddenly available (and Lisson Gallery’s Greg Hilty and the curator Norman Rosenthal were extremely supportive of the project); perhaps I recognise that even more now, as over the past few months people have become busy again.

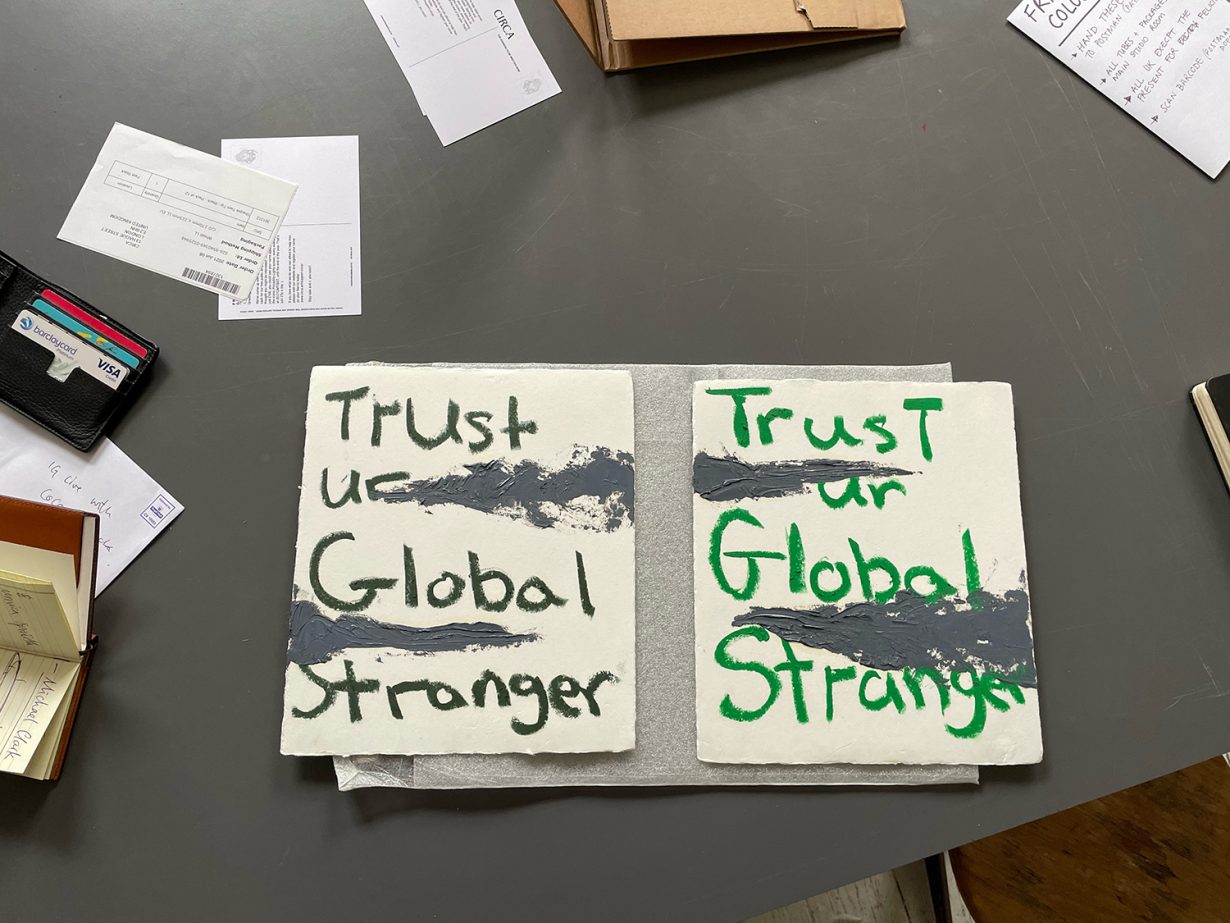

During the first lockdown, in 2020, I did a project called ‘Face Valued’, for which I made 100 canvases, painting them each with a value between £1 and £100 before selling them online for face value. I gave all the money (£5,050) to The Soup Kitchen in Holborn, which ended up making no sense at all because I also needed to pay my bills and survive in London.

But when it came to CIRCA, that fed into the project, and almost overnight it’s become an economy. The screens are one element, but ultimately we’re driven by purpose. We sell prints each month and those prints help to sustain the project because there would be a contradiction if we were to then suddenly be entirely sponsored by a lifestyle brand or an entity that might otherwise be using the advertising lights for commercial reasons. It’s important to maintain that balance and protect the project’s integrity.

AR Presumably the owner of the lights wouldn’t allow that anyway.

JO’C Quite. A friend said to me, “Sometimes there are opportunities in life that are just great but also really difficult.” This was one of those. It wasn’t easy getting it off the ground because of the way that you want it to be a platform that stands for something important and that says something meaningful. But there’s also a challenge in giving the artists that freedom to be able to express themselves within a public space: there are limitations on nudity, or on how far you can go politically, and things like that that you just don’t experience in the white-cube environment.

AR What do you do when those things come up, as they have?

JO’C To begin with I created a council. Now we also have a code of conduct that provides guidelines to artists.

AR Who sets the codes of conduct?

JO’C Because it’s public space, it’s an agreement with Westminster Council. Interestingly, Piccadilly itself is a listed building. If you go and watch an advert and it turns to full screen, there are still three screens to the side that honour the iconic patchwork that make the lights so recognisable around the world. In a break from tradition, [Piccadilly Lights owner] Landsec supported us in gaining special permission from the council to allow artists the opportunity to use the entire screen every day. Something that even the brands cannot do. This is one example of how I had to learn to negotiate between the paradigms of capitalism and protect the interests of artists very early on.

AR Do you approach CIRCA as a curator or as an artist?

JO’C I think that I’ve always been searching for a platform myself. I can get very stuck in my head, and what I love about working with artists on this project is the ability to jump from one idea to the other each month. The project is, in some ways, an archive: you dive into that shelf, you get a sense of, say, what Cauleen Smith [who produced a work for November 2020] was thinking about at that moment, and so on. All I’m doing is deciding who the authors are for each of those 12 volumes. So I’d say that I approach it as a conceptual thinker, and that then influences the way that the artists take up the baton and respond to it each month. I’ve always thought about it is as a bookshelf containing 12 books that form a diary of a year. It invites a definition of what art is: ‘How do you see the world today in CIRCA 2020, 2021 or 2022?’

AR In some senses with projects like this, you’re entering the public’s space, as opposed to a gallery where they choose to enter your space. And with that comes a greater responsibility to keep them interested.

JO’C Yes, absolutely. I think that also brings with it a huge amount of responsibility that includes maintaining a diversity among the artists that we’re choosing, opening up the opportunity. We just did a project called Class of 2021, an open call that drew 2,000 applications. In November 2021 we presented Hetain Patel in collaboration with the Film London Jarman Award, who was really aware of that kind of responsibility. He mentioned that from his perspective minority communities don’t often appear on the Piccadilly Lights or feature within mainstream advertising. His commission acknowledged this in the way that Vina Ladwa [an Indian Kathak dancer playing the role of Patel’s grandmother] proudly took ownership of the screen.

The work explored his perspective of immigration and honoured his grandmother, in a trompe l’oeil setting like those we associate with Queen Victoria. It was a really powerful expression of how the platform can engage with its setting and enable artists to present an idea around the world.

AR CIRCA is not just about working with artists

JO’C I think the circular economy element is what best defines CIRCA. That’s what gives us purpose beyond just promoting an artist. We also collaborate with and support other spaces. We have awarded £5,000 grants to The Showroom and to Chisenhale. Then Zoé Whitley, Chisenhale’s director, commissioned Nikita Gale to produce one of the artworks. As an ecosystem, I think it’s quite unique in its model. It’s required a lot of explaining, because in the artworld many people’s first reaction was, “This isn’t going to work. No collector’s going to want to buy a print for £100.” But the print sales have since allowed us to cover our costs and enabled us to return money to the more general art ecosystem. People want to own beautiful art objects that they can afford. Things like the Patti Smith prints [series of four timed-edition prints created for the #CIRCAECONOMY in January 2021] are unique because she offered to sign all of them. That’s unheard of. We didn’t advertise or promote the fact that they were going to be signed. It was more at the end, she said, “I’ll sign them. My people like signed things.” In that regard, it’s also what I love about CIRCA: it’s bringing the best out of the artworld ecosystem. We recently set up two scholarships at Goldsmiths with £30,000. One is going to be for the MA curatorial course, and another is for the MFA in Art & Ecology course.

AR And the artist gets a fee?

JO’C We give the artists £4,000, which I’d like to increase. I think that’s really important. It’s a very strong responsibility. What I’ve also learned is that you can’t be giving away money and then not paying your people properly either. I’ve learned this as the project and the team supporting it have grown.

AR How do you choose the artists?

JO’C I think when you’re doing something public you really have to remove your desire and your ego from the process a bit, because you’ve got to really think, “What does the audience want to see and what should the audience be seeing that maybe they wouldn’t be seeing if I wasn’t in this position?” There are ways I try to make that work.

One is through collaboration months, when I delegate the choice to a curator. As I mentioned earlier, Zoé Whitley picked Nikita Gale, and Elvira Dyangani Ose, then the director of The Showroom, picked Cauleen Smith. Beyond that, the project can evolve organically. David Hockney [who showed in May 2021] was the first artist that we went international with. Up to that point artists had screened multiple films – three, four or even 30 in the case of Ai Weiwei; no one had showed just one work, as Hockney wished to do. We were talking about John Berger’s theory around repetition and reproduction and decided that it would be great to see this appear in multiple spaces without knowing if we could get those other screens. With Hockney, we were able to get the conversation ignited.

Greg Hilty at Lisson introduced me to gallerist Hwasun Barakat in Seoul, who then worked with me to persuade the largest screen in Korea to participate. Then we reached out to Yunika Vision in Tokyo. Somebody in the studio had a contact for Pendry Hotels in LA. We thought there had to be one in LA because it’s Hockney. Then I met [Futurecity’s] Sherry Dobbin, who introduced me to Jean Cooney from Times Square Arts, which resulted in this global collaboration. Then, post-Hockney, we continued with Korea, LA and Tokyo, and now also have Milan and one screen in Times Square. For now, that’s enough, because it’s also a lot of editing to get the files prepared each month. We also have the website, which has received over 40 million hits since launching. The footfall at the screens could have been zero on some evenings during the lockdown, and it’s this duality between the commissions being online and offline that I find really exciting. For December we dedicated the platform to commemorating the 40th anniversary of the AIDS pandemic. I wanted to give that community visibility, so Maureen Paley introduced me to AA Bronson, who reworked the iconic Imagevirus. And now I’m trying to find ways to break away from the screen and bring things to other spaces.

AR Is that the ambition for the project more broadly?

JO’C I wouldn’t say it’s like an ambition more broadly. But I don’t want to be defined by the screen. I think it’s about finding ways to involve and collaborate and bring more people into different iterations of the project. I think it should remain unpredictable. It should remain inspiring. I think that the minute it becomes a very easy project of making a 2.5-minute film once a month, it’d just be too easy. We have this saying in the studio, ‘Sounds impossible, let’s do it’.

AR At the same time, by using the advertising screen, you’re also validating that space and creating value for it.

JO’C I think that there’s always an exchange. I think that what’s great is that in the heart of London and elsewhere around the world there is now this platform that is offering free culture outdoors. My hope is that it will continue.