Artists in the capital are shaping visions for contemporary art and its institutions in Ghana and beyond

At a panel discussion I attended in December at Accra’s Goethe-Institut, convened under the broad umbrella of ‘let’s talk about African art’, curator Nuna Adisenu-Doe decried the lack of infrastructure and support available for artists in the country, but pointed to the number of galleries opening in Ghana as a quantifiable indication of change. In 2006, he stated, the country had only five galleries showing contemporary art. Now there were over 30, evidence for how things were growing, and for the potential shifts to come.

The talk’s chair, writer Elizabeth Ofosuah Johnson, then posed a loaded question: “What is contemporary African art?” How to define what art these galleries are displaying proved slightly more difficult for the panel to pin down. Figurative painting might dominate the international art market’s hungry definition of current African art, with Amoako Boafo as the local poster boy of success – and, indeed, the majority of what was on display in Accra’s art spaces in early December was portraiture, or minor deviations thereon. At the Nubuke Foundation, which focuses on textile-based work, the angular brutalist building held Halimatu Iddrisu’s stylised portraits of young women, with blank-faced sitters posed against colourful patterned cloth backdrops; while at Worldfaze, a space opened by painter Kwesi Botchway, Daniel Tetteh Nartey had a humorous and surreal slant on the genre, strewing disembodied blue heads and limbs across domestic scenes. At the Foundation for Contemporary Art (FCA), on the grounds of the W.E.B. Dubois Centre, an exhibition curated by the South African initiative Nothing Gets Organised, stood out from what else was on offer in the city by virtue of holding a range of sculpture, installation and videowork, dispersed around the grounds and museum of the worn complex.

At the Goethe talk, the obvious issues inherent in trying to define ‘African art’ as any singular entity quickly erupted. As Johnson noted that “a lot of what’s making contemporary African art is not in Africa”, American artist Laurel Richardson asked from the audience if any such definition would include the African diaspora. The third panellist, Gabriel Schimmeroth, a German curator at the ethnological Museum am Rothenbaum in Hamburg (joining via video), raised the issue of how African artists were often expected to perform their nationality in their work, in a way other artists might not be expected to. He pointed to a 2022 project he’d worked on with Ghanaian artist Kelvin Haizel in Hamburg, where Haizel drew on a photographic album in the museum’s archives that held nineteenth-century images from Singapore to make a body of work that, as Schimmeroth put it, “wittily avoided the framework of African art”.

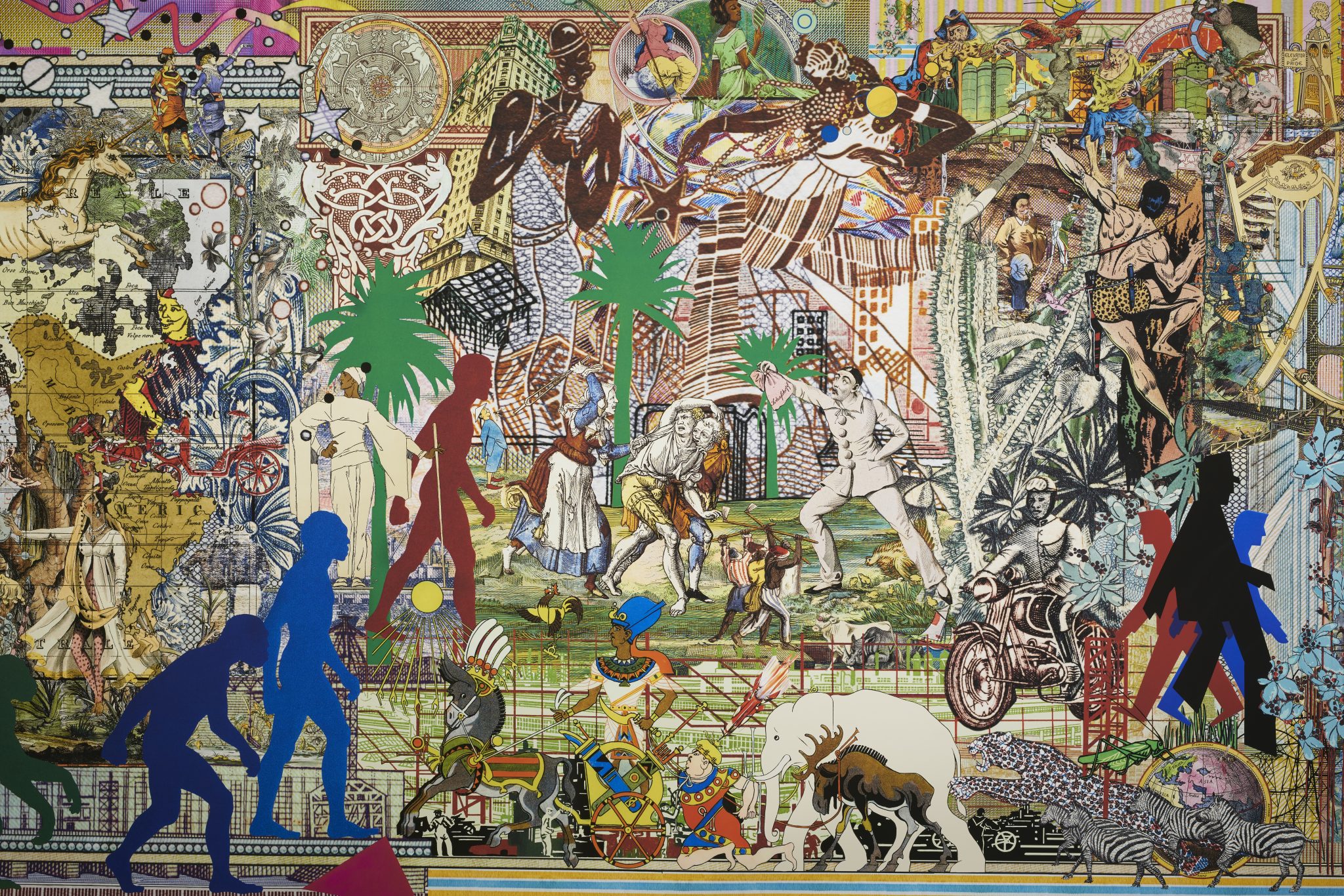

During my visit to Accra, Haizel was in residency in a studio in the half empty mall that houses several of Gallery 1957’s multiple exhibition spaces, preparing new work for a show. The residency-exhibition model is common in the city, with 1957, Worldfaze, Boafo’s dot.ateliers and the Noldor Artist Residency all bringing artists from across Ghana and internationally to make work onsite for display at the end. Haizel’s work has long drawn on photographic processes, but the studio was full of vibrant abstract paintings that at points resembled pink camouflage, at others dense autumnal scenes of foliage, at others still a frenetic choreography of smudged finger marks in deep blues and earthy reds. Upstairs, 1957 held a group show of 19 artists curated by British writer Ekow Eshun, where work by international-circuit names like Boafo and Zanele Muholi sat next to Malagasy-French Malala Andrialavidrazana’s expansive, eight-metre-long satirical digital collage (2022), mashing together imagery from currencies, textile patterns, cartoons and old maps, and American Kenturah Davis’s series (2023) of pencilled portraits that sat above neat swatches of woven fabric, as if encoding some hidden information about the sitter. Gallery 1957 might provide one vision of what art in Accra is currently: largely wall-based, illustrative and polite. Haizel, however, is also part of the Exit Frame Collective, which seems to be part of a broader coalition seeking a more discursive, open-ended vision of art’s possibilities in the city.

Exit Frame has worked loosely as a curatorial endeavour since 2012, working for example as part of the curatorial team of the recent Ljubljana Biennale. Since 2020 it has been running the annual temporary art school experiment CritLab – which is what brought me to Accra, where I had been invited to take part as a facilitator, alongside figures like Richardson, Oyindamola Fakeye (curator of the CCA Lagos) and curator Marie Hélène Pereira (formerly of RAW Material Company, Dakar, and now at HKW, Berlin). Self-described as a project that ‘strategically combines the formats of art academy, residency, workshop, laboratory, and professional development programme’, CritLab is a free two-week intensive gathering for a dozen participants, this year including artists, writers, musicians and a choreographer, all hailing from Ghana and Cameroon, as well as an Italian curator. Some had had work featured in international magazines, some had never done a public exhibition.

The three days of CritLab I experienced, held in the FCA, bounced between structured discussion – on Ghanaian art history, or practical tips for documenting work – and talks (via video and in person) by the range of guest facilitators. All the while, participants made multiple presentations on their own work, their ideas and the spaces they’ve worked with, drawing on feedback to hone their presentations further with each iteration, creating a condensed, repetitive loop towards some kind of clarity. Never far from conversation were two figures, held up informally as godparents to a more Afrocentric contemporary art scene. The first was Bisi Silva, founder of both CCA Lagos and the Àsìkò programme, the latter an influential six-week pan-African exchange initiative, running since 2010, that was an inspiration for CritLab and has been a meeting point for many of the people facilitating the December sessions (after Silva passed away in 2019, Fakeye has continued the project, with another iteration expected next year). The second was kąrî’kạchä seid’ou, head of the art department of KNUST Kumasi, a galvanising figure in shifting the art school towards collaborative and lateral forms of art production, and one of the driving forces behind the blaxTARLINES collective of artists and curators, also based out of KNUST.

While exhibiting the usual distractions of any art education environment – crossed wires, circular arguments, wandering attention – what emerged in my brief exposure was a sense of openness, a levelling of access and the seeding of long-term conversations. Previous participants encountered over my week in the city constantly recalled what CritLab had meant to them, giving critical discussion they hadn’t found elsewhere. At another session I took part in, several people visiting the DuBois Centre just wandered in, and became part of the conversation without a second glance.

Closing off the talk at the Goethe, Johnson acknowledged that African art was having a moment internationally, but then asked, “What is the future after the trend for African art fades?” Adisenu-Doe posited that, for long-term sustainability, “the state will need to be involved”, to create institutions that would support Ghana’s artists. But as Accra’s residency-exhibitions and events such as CritLab show, in short, intense bursts, its artists are already building their own institutions.