ARTREVIEW

Hi. Have you been casting spells?

MERLIN THE WIZARD

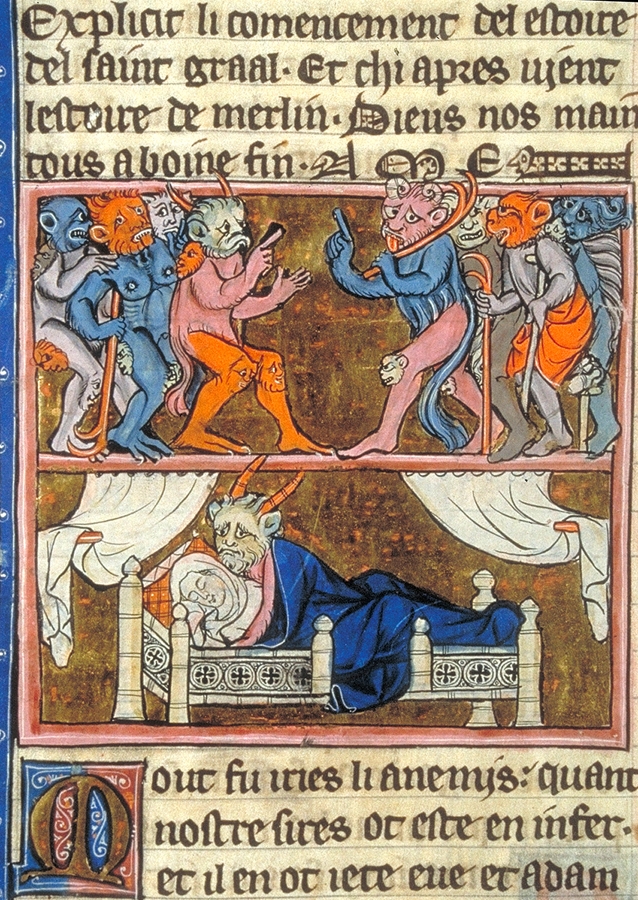

Not so much. This isn’t an age of my kind of spells; but it’s certainly an age of enchantment. At least if you think of the power of advertising and promotion, what Walter Benjamin calls ‘phantasmagoria’ – a world of illusions created by the mass media, in which modern people find models for their everyday behaviour but also their attitudes and prejudices, and even their deepest beliefs. He is expanding on his own ideas about the arcades in Paris, during the nineteenth century, via Marx’s notion in Capital of the phantasmagorical powers of the commodity. Rather than spell-casting, I’ve been reading writing on art.

What magic terms did you find there?

MTW Instead of Moloch and eye of newt, I found Tracey Emin and greatness; that’s where modern incantatory meaning is at its densest, in the sense that the structure imitates ads for new cars.

You mean Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. What’s so bad about his review of Emin, as art writing?

MTW He’s not joking when he says the exhibition is ‘a lesson in how to be a real artist’, and things like, ‘Great drawing has to be done from life’ – and, ‘She’s looking in the mirror and striking a pose, just like the old masters did. She just happens to be naked when she does so.’

They are legitimate opinions, aren’t they?

MTW They are subjective in a way that is out of control. Objectively, drawing has no fixed definition and is a constantly changeable form. This is so even in the West, where the concept ‘Old Master’ has a meaning but an inextricable part of it is that Dürer is different to Tiepolo. The meanings of portraying oneself, and processing ‘life’ as art, are also changeable if you are thinking historically as opposed to dreamily. If all this dissimilarity through the ages and around the world has now become a uniform totality, how was that accomplished? It was in fact the illusion the show succeeded in creating, at least for an audience already conditioned to believe in this artist’s greatness. It made them fall into an even deeper sleep and dream that Rembrandt had returned as Emin. It may well be that there’s an achievement there, but it’s a complicated one. The review doesn’t step back and consider it, but attempts instead to climb up onstage along with the magician and imitate it.

What’s wrong with subjectivity?

MTW I like it when Sean Landers vents about it, because there is a modernistic concern with language as raw material. That used to be true of Emin as well. Like him, she violently deformed norms of linguistic usage recognised in many contexts involving art and writing, and used conceptual art strategies to line up the products and make magic sense of them. In fact it was within the same few months during the early 1990s that her first show at White Cube was staged and his novel was published, entitled [sic]: the Latin term employed in publishing when correcting texts to mean, ‘This is how it was written, even though it seems questionable’. The book is a facsimile of handwritten, all-capitals, nonparagraphed scrawling for hundreds of pages. His dyslexia is allowed to stand, as well as the rambling quality of his thought processes. The narratives that emerge become more and more engaging. Knots of content build up in which are entwined descriptions of art and artists (‘ON KAWARA BIG DEAL FAT MAN IN SANDELS’) and attempts to understand identity (‘THERE’s NOT AN OUNCE OF MIC OR GRIK SENSABILITY IN MY LAZY AMERICAN ASS’).

OK. What other art writers do a better job than Jones?

MTW One is Griselda Pollock. Her book Differencing the Canon, published in 1984, includes an essay that looks at several women important to the story of Manet’s practice. We don’t learn by the end that they are just as great as him, but that artistic achievement while real enough on its own terms is always also a mythology in which structures of domination play a role. Another is Julia Kristeva, an important influence on Pollock. You might think the famous opening paragraph of Kristeva’s 1980 book, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, would make an appropriate epigraph for the Emin show, especially if you substitute ‘art’ when the word ‘literature’ is mentioned. But Kristeva’s Rimbaud-like poetic writerliness would put the show’s visual complete deadness in the shadows. ‘Throughout a night without images but buffeted by black sounds; amidst a throng of forsaken bodies beset with no longing but to last against all odds and for nothing; on a page where I plotted out the convolutions of those who, in transference, presented me with the gift of their void – I have spelled out abjection. Passing through the memories of a thousand years, a fiction without scientific objective but attentive to religious imagination, it is within literature that I finally saw it carrying, with its horror, its full power into effect.’

Tremendous! What else?

MTW Because art is a made thing as well as the bearer of ideas, there’s always an interesting contrast of differences involved in writing about it. There’s a visual object, something you can perfectly well see for yourself, and which has a lot of visual complications, which can’t easily be described in words. And then there is everything you could possibly bring to the object in terms of the whole body of ideas about it that is already well established, and for which the object acts as a trigger. It directs you to those ideas, which are assumed to be the entirety of the experience, as if that other thing that is not them – the visual object that is also there, the made thing – is not really there at all, or was long ago disposed of as an issue. An essay by T.J. Clark on Abstract Expressionism, in his 1999 book, Farewell to an Idea, is a great example of writing on art that can dramatise and eke out vivid content from that dichotomy.

Cézanne is a great enchanter but different to Clark in that in his letters he reveals truths without seeming to know he’s doing it

What about historical art writing?

MTW Cézanne is a great enchanter but different to Clark in that in his letters he reveals truths without seeming to know he’s doing it. In a famous one, you’re being told something about simplicity. It is to the Symbolist painter Émile Bernard, who’s just visited Cézanne: ‘May I repeat what I told you here: treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone…’ The quote comes to mind because of its bold straightforwardness about an elusive artistic idea. Few really comprehend it. When I say simplicity, I don’t mean the message is that if you wish to depict nature then you should see things in nature in a simplified way so they can be made into art. I mean I think he’s saying that in his view a painter seeks out simplified large forms in the painting that’s being created, into which can be arranged complex visual content that comes from nature. But in relation to this quote, I always think of another less famous one in a letter to his son. Here he mocks Bernard and gives him a ridiculously fancy name: Emilio Bernardinos. He says this character’s art is rubbish, he’s full of fantasies and he has no feeling for nature. He adds the caveat that he’s sure Bernardinos is right in the praise he offers to Cézanne in a letter that Cézanne is passing on to his son for him to examine.

There’s a distinct impression that Cézanne is expressing fear. He even ends suspended in midair, as if he’s temporarily unsure who it is he’s addressing: ‘You will correct me if I am mistaken –’. For me the two letters, 28 months apart in time, with their light and darkness, comprise an equivalent of Clark’s observations on Abstract Expressionism’s ambiguity; this art movement that in Clark’s view demands that its audience refine itself and at the same time partly panders to the audience’s vulgarity. The interest of Clark’s essay for me is the praise/attack rhythm, giving and taking away, or affirm/refuse. And likewise, Cézanne’s second letter disturbs the earlier one. You hear something more in what he’s saying there if you think of what he’s saying by mistake later: the task of artistic organisation is impossible and attempting it goes with endless dismaying personality disintegration.

If these are spells, what are they doing?

MTW Something is undone: the obvious. An undoing of the habit of seeing work by artists like Cézanne, or belonging to movements like Abstract Expressionism, as part of artistic appreciation that doesn’t require new thought. Clark’s ‘In Defense of Abstract Expressionism’ is self-consciously clever criticism, written for a cultured audience capable of enjoying the contradictions he dishes up. Cézanne’s letter to a respectful but uninformed son is a pathetic confession of doubt disguised as scornful dismissal of another’s weakness. They are literary utterances in different modes possessing different levels of awareness. But in each I value the revelation of truth through integration of contradictions.

What do you think of Artforum?

MTW It is as delicious as a human body created by a warlock. A lot of the images actually are bodies. Fashion bodies in the many fashion spreads, for example, or images of painted bodies, or bodies in videos. They are experienced along with the physical objectlike substance of the magazine when opened up, with its sheeny curves and promising gully.

Phew, it sounds great!

I’m attracted to the knocks dealt by art critics to zombie abstraction

MTW With all this body feeling it is almost not surprising that there is so much ownership on offer as well: private collections, museum collections, auction sales of peoples’ collections. It reminds you that often writing on art is encountered in a glossy context. You can consume it without reading it. Obviously it’s different if you do read it, and I’m not saying reductively that the writing is always unreal or doesn’t matter.

Anything else that’s bewitched you?

MTW I’m attracted to the knocks dealt by art critics to zombie abstraction: these paintings by Oscar Murillo and others, falling out from the market success of Wade Guyton. Works of art are selected for acquisition by speculator-collectors based on certain repetitive features. They show signs of process, and they’re abstract but not in a tradition of abstraction, more a tradition of postpainting, societally critical conceptualism. Only not actually that but merely nominally that: that is, they don’t have much to say, but what little there is has to be explainable in the gallery press release in terms of critique. A lightweight version of important content is accompanied by a visual impression of hands-off effortlessness. Plus they’re mass-produced. It’s incredibly effective financially. This magic-spell onslaught by the art market has been countered by spells flung back by critics – they say it’s only the market that’s significant in the zombie abstraction phenomenon. They don’t mention that art-market speculators at the moment have far more power to affect culture than critics, or that the zombie triumph is only the most transparently obvious sign of today’s critical impotence.

On the other hand, these discussions are intelligent largely because the work in focus does not awe the critics and they feel they can give it a good kicking. And in feeling relaxed in that way, something becomes uninhibited in their descriptive energies. As a result the artworks become intriguing for the reader simply because the degree of sheer information about them on offer is so high. Between the market, the artists, the collectors and the critics, it’s a spell crescendo. But spells aren’t real. You’re left with an impression of moves in the artworld. And a feeling something like: ‘Hmm, yes, moves. They have their limitations.’

This article was first published in the December 2014 issue of ArtReview