Tucked under the velveteen fuzz of this tame church lady’s Easter dress is something sticky, a splurt of nectar that slobbers from lips and drips down chins. A colour drawn from the sliced flesh of a fresh peach, that hairy little heartstone is a tooth-chipping dirty joke underneath all that lovely sweet meat. “I really love your peaches, want to shake your tree,” croons Steve Miller in his ‘pompatus of love’. A wholesome desire, carnal without corruption, its colour a soft blush on a virgin’s face: even a toothless oldster can gum one and feel the sexy life of this pliable stonefruit as it dribbles down through creased skin, syrupy fruit one of the few sensual pleasures left to those at a late end.

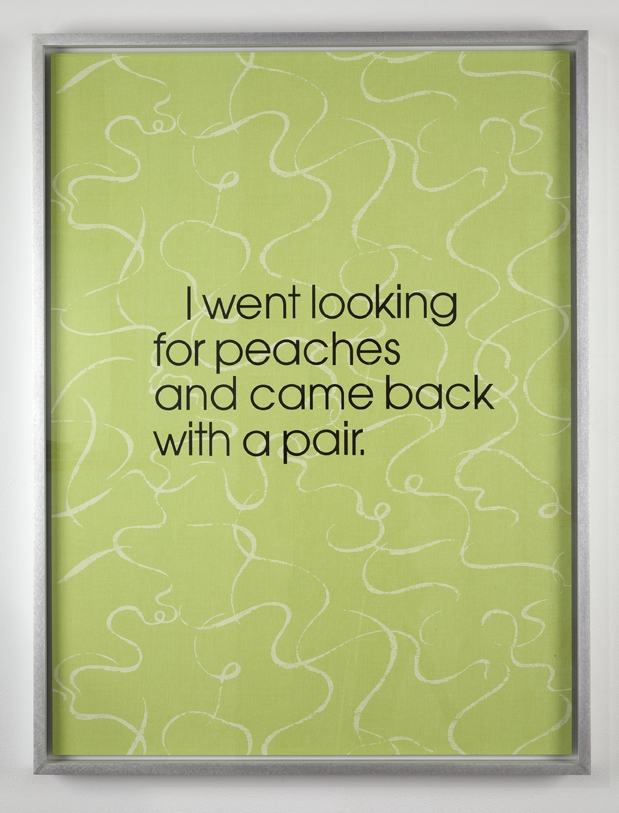

While Georgians and South Carolinians like nothing better than proclaiming their peaches, it is on the mountain slopes of China that this drupe first drooped. First pictured lingering on a Pompeian panel, the peach still-lifes throughout tourist-tramped miles of museums. For Caravaggio the plump little beauties, invariably handled by handsome young men, glow in these gentlemen’s baskets and hands like a couple of gently shaved balls. When Haim Steinbach, master collector, organiser, revealer of bric-a-brac meanings, posts in a print on found wallpaper in 2011, ‘I went looking for peaches and came back with a pair’ – well the lust is as plump as the fruits, but so is their possession.

Peaches promptly belong in modern art, looking a little sickly in Manet and robust in Renoir, but it’s Cézanne who best brushes the soft colour into preternatural appeal, alluding and eliding, softening and blending, when some Calvinist Netherlander might make that mouthwatery succulence look all stone and no fruit. ‘Painting from nature is not copying the object,’ Cézanne said, ‘it is realising one’s sensations.’ You know Picasso’s channelling his only master when he says, of notably dubious attribution, ‘One does a whole painting for one peach and people think just the opposite – that particular peach is but a detail.’ But a painting of a peach isn’t really a peach after all, ceci n’est pas une pêche.

But peaches certainly don’t belong to boys alone. “I’m amorous but out of reach, a still life drawing of a peach,” sings Fiona Apple (her tart bite is better for her eponymous fruit). Marilyn Minter harrowingly details each delicate hair on a woman’s face in her work from 2003 called of course Peach Fuzz. The Teaches of Peaches (2000) has the songstress clearly declare in each word and turn of her hard struts that a little fuzz is fun for all mouths.

Peach is not lust, just the suggestion of it, the sensuality a dream of possibility, and so this soft tone fits fully as another of those colours that oozed out of California in the 1970s. Goldenrod and avocado for the kitchen, peach for the bed and bath. A cover shade of a Rod McKuen book; a leisure-suit hue for cocktailing in the Hills; the beachy watercolour on a brochure for a cult. No mystery that the 1960s finish-fetishists found room for peachy sheens, as did James Turrell in his softly lit chambers; we understand why the colour leaks through the sci-fi landscapes of William Leavitt, or more recently colours the paintings of younger practitioners: in Friedrich Kunath’s coastal dreams and tie-dye washes, in the cryptic peachy poetry of Alex Olson’s action-packed screens, folded in a cracked chevron in a Rebecca Morris abstraction or as the background hue in Dianna Molzan, flecked like a fastfood countertop. It is a sunset colour seen through smog, a juice smear of light at the beginning or end of the day over the sea.

Peach begins as a fruit, but this soft shade clearly peaks in apotheosis as a colour, the pure embodiment of itself, a gummy lusciousness that by any other name is just as peachy.

This article was first published in the December 2014 issue.