The atmosphere at musician Terre Thaemlitz’s talk at Café Oto in London smelled cultured and expensive – too much Comme D and Le Labo. A friend who loves perfume would say that they were ‘scents with strong sillage’ – French for wake and the ‘correct’ way of referring to the musky trails that fragrances radiate: invisible reminders of physical presence.

Thaemlitz, who is based in Japan, spoke about silence and withdrawal as strategies of resistance. Hostile towards the online ‘sharing economy’, she began by quoting a 1979 interview with Susan Sontag, published in Rolling Stone: ‘You want to share things with other people, but on the other hand you don’t want to just feed the machine that needs millions of fantasies and objects and products and opinions to be fed into it every day in order to keep on going.’

I go through my notes the day after. Written in the corner of one page is Japanese saying: ‘reading the air’.

Kuuki wo Yomu, which translates awkwardly in the English tongue, means to be sensitive to the atmosphere of social situations – to be aware and to value what’s unspoken between a group of people. In order to avoid conflict and remain polite, it’s important to be perceptive to the ‘air’, to read and obey it. ‘KY’ is an abbreviation with negative connotations used to describe people who ignore the ‘air’: those who say too much or not enough, who say things at the wrong time, who stick out.

I go on an online forum for expats, read a comment from yagian, ‘an ordinary Japanese salaryman living in Uptown Tokyo’:

‘I’m trying to be “KY”, even if someone is angry at me, because I believe that nothing will come out of “reading the air.”’

Recent exhibitions by Anicka Yi, Michael E. Smith and Anne Imhof, all of which I’ve experienced over the last six months, have activated atmosphere both as material and conceptual tool. I’ve read their air and made connections between the ways they employ reductive processes – be it taking away light, replacing speed with slowness or prioritising smell over sight. These removal strategies provoke us to pay attention differently. They challenge sustainability, clarity and productivity as dominant languages that ‘feed the machine’, Sontag observed more than 30 years ago.

We are unsure whether to attribute atmospheres to the objects or environment from which they proceed or to the subjects who experience them. We are unsure where atmospheres lie

As that awkward translation ‘read the air’ suggests, it is difficult to define ‘atmosphere’ in relation to artworks. A total phenomenon, largely nonrepresentational, an immaterial quality that’s felt. ‘An atmosphere is neither an object, nor a subject; neither passive nor neutral’, argues German philosopher Gernot Böhme. We are unsure whether to attribute atmospheres to the objects or environment from which they proceed or to the subjects who experience them. We are unsure where atmospheres lie.

In his discussion of West Coast Minimalism from the 1960s – think Larry Bell’s transparent cubes or James Turrell’s Light and Space experiments – Dave Hickey writes about the work harnessing atmosphere as a benign presence. The artists cooked materials like chemists: oxygen, neon, lacquer or chrome – ‘this is a world that floats, flashes, coats and teases’ – exposing the fullness of empty space as it flirts with the boundaries between object and atmosphere, mind and body, self and other. This atmosphere was elegant: ‘California Minimalism created a gracious social space in its glow and reflection.’ It was also durable. Look at a work by Peter Alexander now and its surface still shimmers like it was made yesterday.

In the wake of perpetual technological updates and rolling news streams, permanence doesn’t feel like something worth striving for any more. A list of mass deaths and apocalyptic visions remembered since my childhood: the Cold War, AIDS, Y2K, the greenhouse effect, famines in ‘Africa’ as told by Comic Relief, bird flu and all the disaster films I tried and failed to watch due to fear. Who needs things to last forever when forever won’t be that long?

Standing in the second room of Anicka Yi’s Kunsthalle Basel exhibition this summer, seduced by her translucent glycerine soap slabs: minimalist elegance now comes in a fragile form. In the bacterial patterns of her Petri dish stickers, I imagined a luxury fashion store at the end of the world: mould spoors multiplying in the damp creases of leather handbags.

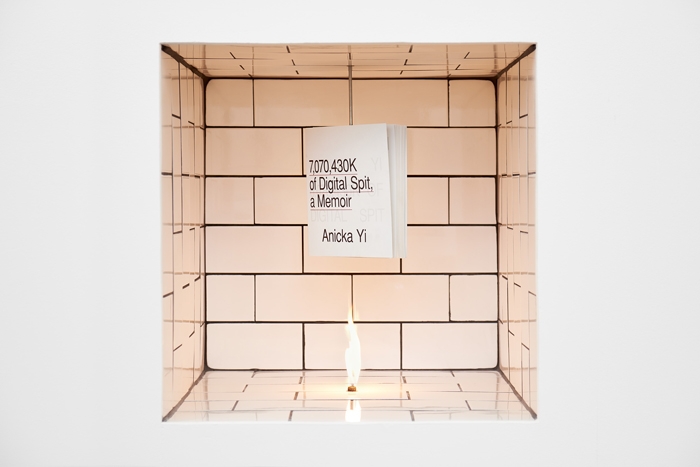

As an experience, 7,070,430K of Digital Spit: A Memoir releases itself slowly, an incremental oozing interrupted by bursts of olfactory sensation. Yi follows a strange kind of recipe, combining unstable organic ingredients such as tempura-fried flowers with cool clinical objects – steel, plastic tubing, ultrasonic gel – to create an atmosphere of instability. With her fragile compositions, Yi stages perishability as something that is intimately connected to our sense of self as it is transformed by increasingly digital technologies.

Their brief: to create the scent of forgetting. The air of the gallery is literally filled with loss

Among these Frankenstein fusings, Yi’s perfume-impregnated exhibition catalogue rotates slowly above a single flame: she asks that you burn it after reading. Heat releases Aliens and Alzheimer’s (2015), the fragrance Yi designed in collaboration with a French perfumier. Their brief: to create the scent of forgetting. The air of the gallery is literally filled with loss.

Resisting remembering provokes a world with no ends, no monuments to visit or minutes of silence to mark. Yi is not nostalgic: she made her muse perpetual mutation. Alongside the soap-slab sculptures are living, shifting paintings bred from the air and samples collected from surfaces of the kunsthalle; they contain bacterial traces of the institution’s every past exhibition, visitor and event.

To make her cultures, Yi sticks swabs in mouths and scrapes genitals. Decorating walls with the dirt of bodies, she fills the air with their many secretions. Like Timothy Morton’s desire for a ‘queer ecology’, Yi challenges the fantasy of ‘Nature’ as something other than ‘human’. Morton writes: ‘Society used to define itself by excluding dirt and pollution. We cannot now endorse this exclusion, nor can we believe in the world it produces. This is literally about realizing where your waste goes.’ Yi harnesses the atmosphere to make us think about how insignificant we are within it.

‘Air has entered the list of what could be withdrawn from us,’ writes Bruno Latour, drawing on the theories of Peter Sloterdijk. Since the use of mustard gas in Ypres in 1915, a science of atmospheric manipulation has been declared. Latour argues that with this activation, air has been reconfigured: ‘You are on life support, it’s fragile, it’s technical, it’s public, it’s political, it could break down – it is breaking down – it’s being fixed, you are not too confident of those who fix it.’ Be suspicious of that which you cannot see, the air might be the death of you too.

Anne Imhof, For Ever Rage, 2015 (installation view, Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, 2015). Photo: David von Becker. Courtesy the artist

It’s September, and I’m watching Anne Imhof’s For Ever Rage (2015) at the Hamburger Bahnhof and trying to hold the dead-eyed stare of one of its performers: she’s giving off bad vibes. Never felt cool enough for Berlin: lack the ambiguity, got a face that shows I care too much. We’re dispersed around the room’s edges, hugging the walls. In the centre, four punchbags hang like pillars above concrete troughs of buttermilk. This stage is a cage: six beautifully strange performers, its animals in captivity. The lights are low and diffused, giving the space that divides us a flat oppressive density. It’s the opposite of spotlighting: we have to decide what’s important. It’s too dark to post on Instagram: this work resists sharing.

Imhof’s performances are long and slow. See them as dances that withhold or images that emerge over time. Clandestine movements such as the hand signals of nightclub doormen or the gestures of pickpockets are borrowed and reworked. These body codes are only intended to be visible to the initiated; in this way they are an intimate but exclusive shorthand. As any school bully knows, alienating atmospheres rely on the strength of the clique.

“What – do – you – want,” the performers chant, finishing each other’s sentences, they all get a word each. It’s a rhetorical question; they sound kind of bored. White bodies in generic clothing: tech trainers, loose-fitting T-shirts, ripped jeans. They look apathetic, entitled in the way that the culturally gentrified do: it’s sexy. A guy bends his knees, covers his face, thrusts his crotch forward and sways his hips. Slowly. I can’t tell if he wants to fuck or fight. At intervals the air smells sweet but aggressive. Stockpiles of energy drinks get cracked open rhythmically, sometimes they’re swigged, most of the time they’re not. The implication: bodies are stimulated into action, penetrated by chemicals. A tortoise is brought out, held in outstretched hands and left to crawl on the floor. Walter Benjamin wrote about tortoises in The Arcades Project (1927–40), recalling the Parisian mid-nineteenth-century practice of walking with one on a leash in order to slow down one’s pace; to look intently at the urban landscape, and to be transformed into the bohemian object of to-be-looked-at-ness.

To slow dance down is to confront modernity’s energetic project of progress-driven, ever-changing motion. In his discussion of choreographer Jérôme Bel’s work, André Lepecki points to slowness as a means of ‘decelerating the blind and totalitarian impetus of the kinetic-representational machine’. Imhof problematises the way we consume the body – we’re given a long time to objectify this beautiful youth, we desire them as they refuse to be productive, to participate. Lepecki argues these unsatisfying slow movements create a body ‘seen less as solid form and rather as sliding along lines of intensities’.

Slowness can be scary too

Slowness can be scary too. “It was never about going anywhere really”, sighs Jay, the cherry-lipped blonde protagonist of It Follows (2014), a recent ‘sex equals death’ paranoia horror film shot in Detroit. Boy-meets-girl teenage romance is actually boy takes girl’s virginity, spunking cum laced with a supernatural curse. “This thing, it’s going to follow you,” he says. The demon doesn’t have a single identity, it’s a shapeshifting apparition, it’s not visible to anyone but the ‘infected’, it doesn’t run, it doggedly walks. The soundtrack is a droning electronic collage of corrupted synths that fills you with dread. Detroit’s planned obsolescence colludes with the film’s no-sex policy. There’s pathos in the girl’s puppy-fat youthfulness surrounded by the city’s architectural decay.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2015, jacket, baseboard heater (installation view, De Appel, Amsterdam, 2015). Photo: Cassander Eeftick Schattenkerk. Courtesy the artist

At first I don’t notice the lack of light in the Michael E. Smith exhibition at De Appel in Amsterdam. The greyness of the day meets the greyness of the gallery in a seamless transition. The lights aren’t just off: Smith has taken the fluorescent tubes away and left the power on. Real or imagined, the air tastes of electricity.

Unbleached fabric scrims mask off most of the windows, outward views are refused, the space contracts. Despite this appearance of separation, light is extraneous to the gallery; our visibility depends on the weather’s whims. After I notice the light, I hear the sound. It’s coming from two monitors in the entrance, the screens are green – night-vision footage – the image is forgettable, the abstracted white noise is not, it follows. Smith’s sculptures are often described as unsettling. The exhibition text repeats the word ‘morbid’ a couple of times. There’s something camp about reading sculptures made from discarded things as ‘dead’.

Smith’s sculptures are often described as unsettling. The exhibition text repeats the word ‘morbid’ a couple of times. There’s something camp about reading sculptures made from discarded things as ‘dead’

Smith can’t shake off Detroit, having lived there for many years until recently, and his work brings its baggage. This city was allowed to crumble slowly, writes Dora Apel in her book Beautiful Terrible Ruins: Detroit and the Anxiety of Decline (2015), its decay the result of a ‘more gradual and hidden process of divestment, emigration and radicalised discrimination’. Detroit made the news in 2009 when a local man was found encased in ice at the bottom of an elevator shaft in an abandoned building: he’d been there a month. Charlie LeDuff, the journalist who broke the story, received criticism from the local white art community for perpetuating the city’s ‘bad press’; they asked, what about the good things? The do-it-yourself initiatives, the hardworking citizens? ‘When normal things become the news,’ LeDuff responded, ‘the abnormal becomes the norm.’

Smith’s work demonstrates just how normal things can become. His objects are made from the most familiar of things: two steel poles run vertically from floor to ceiling, a pair of XXL tracksuit bottoms crumpled at their base like trousers caught around ankles. In the same space, two seedpods fused to a pair of nail guns are fixed high up on a wall. Objects of potential construction, be they plants or houses, have been decommissioned. Despite this, they resist categorisation as either dead or alive: it’s ‘choose life’, but not as we know it. In the material interventions Smith performs on these objects – dipping hooded sweatshirts in rubber, removing the weighted bases of pallet jacks – he activates an atmosphere of stasis: the ‘edgelands’ of urban spaces aren’t out there; the wasteland is in your head.

I’d seen the exhibition with a friend; he couldn’t get over how affective it was in its lack. Afterwards, stoned from joints smoked while wandering through Amsterdam, we talked about the show as a kind of antiexperience, a nullifying retort to the spectacle of total installation. A couple of months later I emailed him about ‘reading the air’. He responded immediately: ‘I’ll keep trying to.’

This article was first published in the December 2015 issue of ArtReview.