Indigenous Australian multimedia artist Destiny Deacon (of K’ua K’ua/Kuku and Erub/Mer descent) is best known internationally for her photographs that depict friends, family and kitsch artefacts in unsettling and surreal scenarios that describe Indigenous trauma, memory, identity and cruelty via the artist’s characteristic visual language of ‘Blak humour’. Among the photographed objects, her collection of Aboriginalia (which she calls ‘Koori Kitsch’) and black dolls are her most frequent muse: “I feel sorry for those little dolls lying in trash and treasure markets… looking all forlorn and stuff. I don’t know why – I just seem to rescue them,” Deacon once said during an artist talk (at the 1996 Asia Pacific Triennial Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art), before adding, “I like the dolls because it’s too much hard yakka getting people to pose… they start swearing at you to hurry up!”

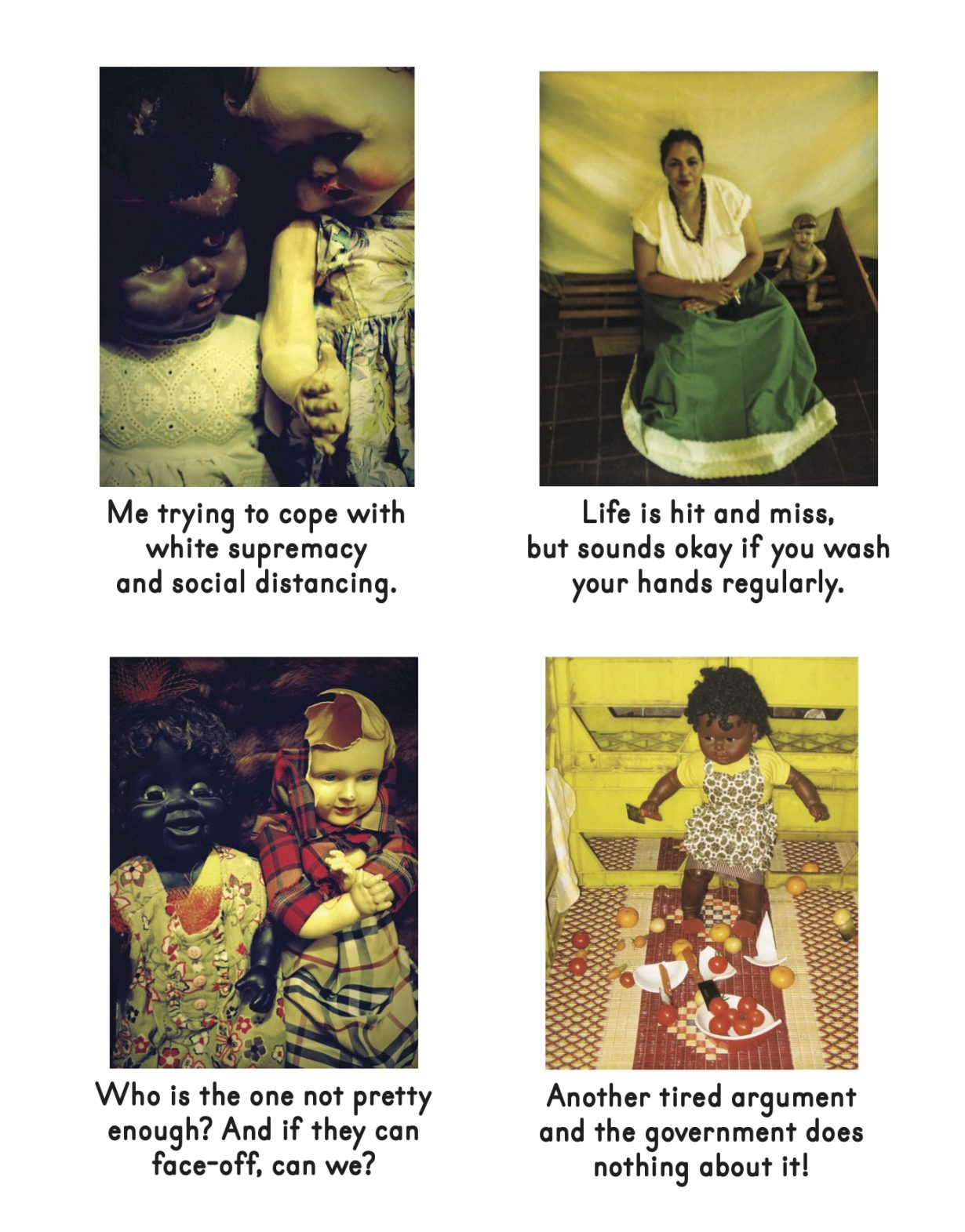

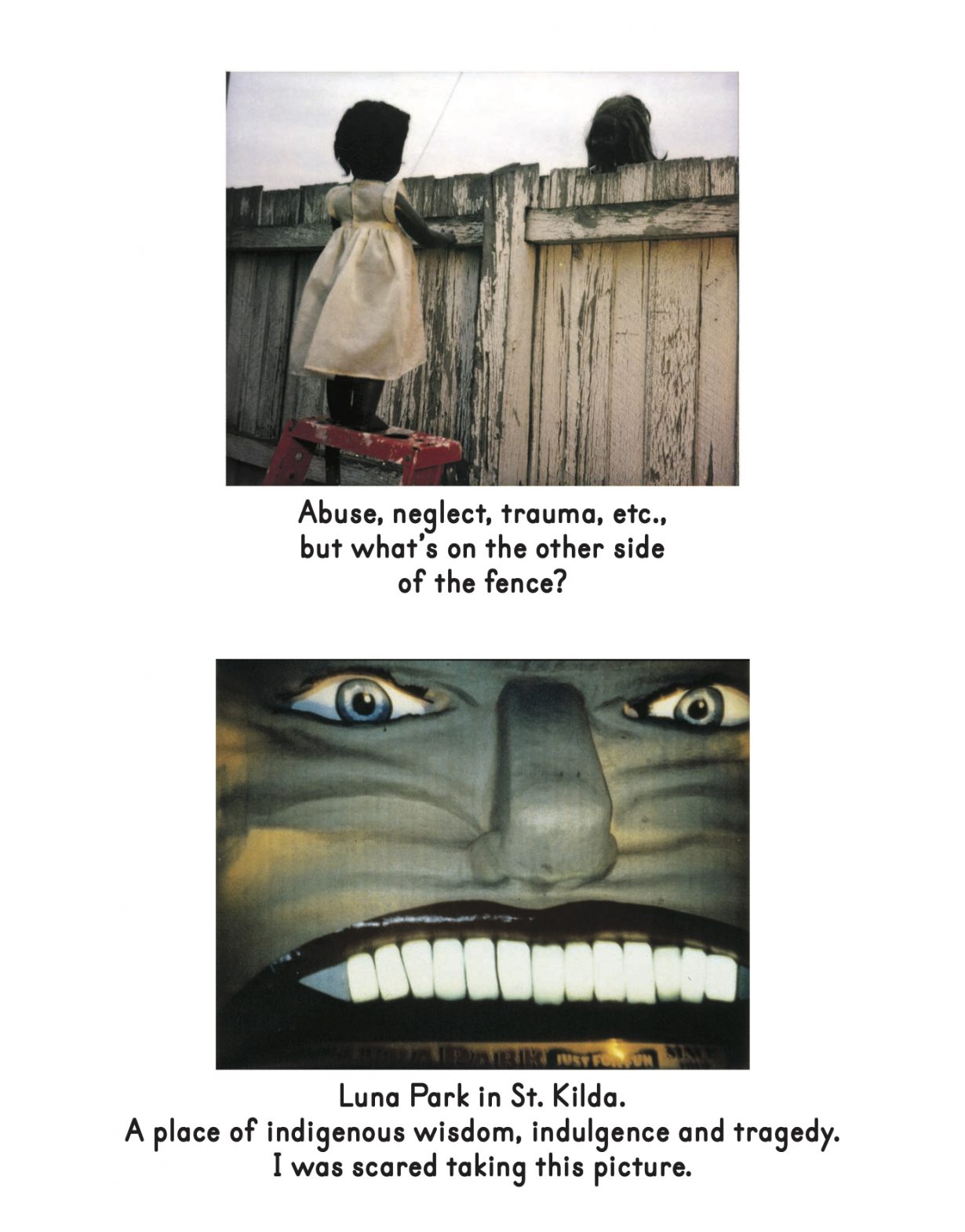

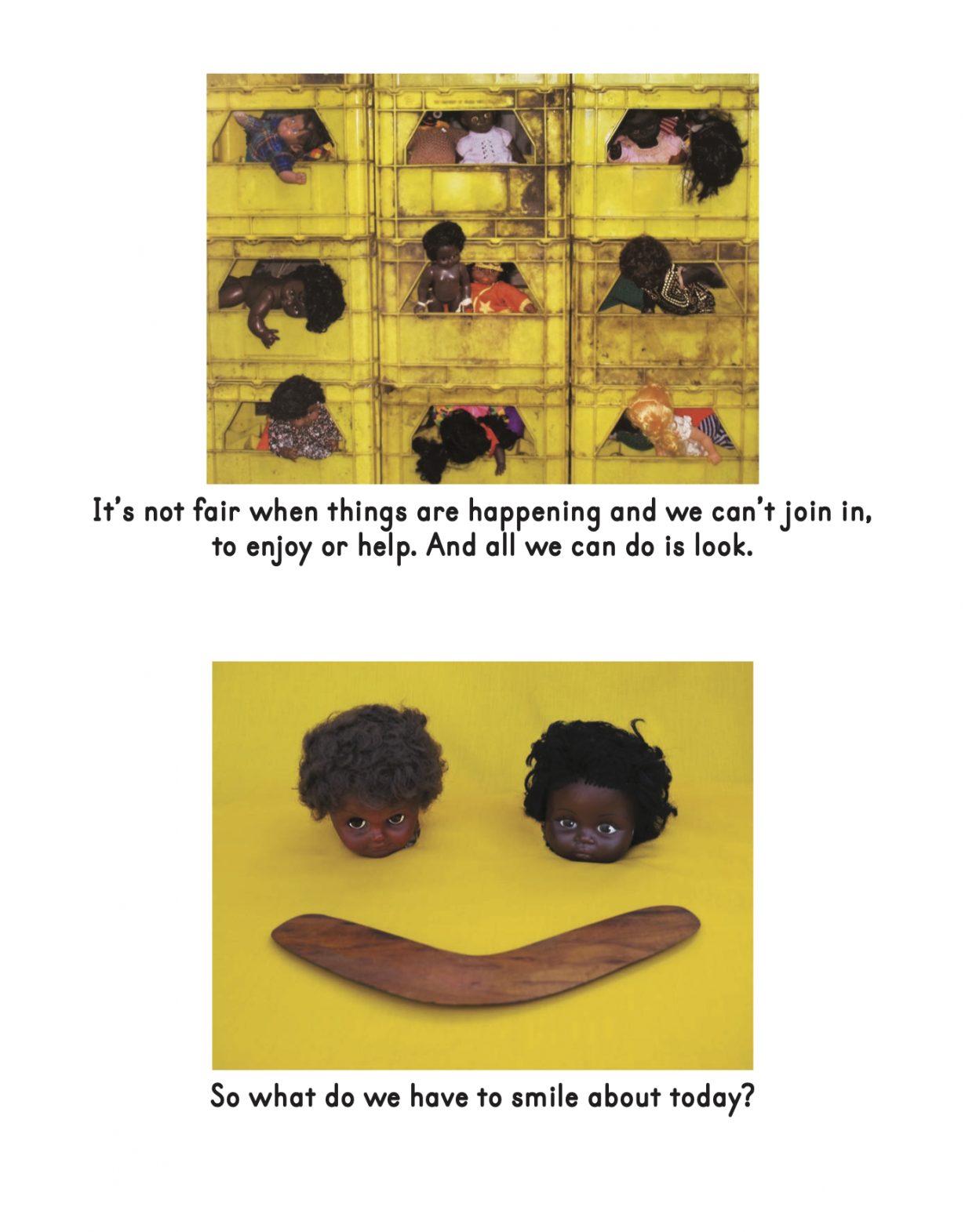

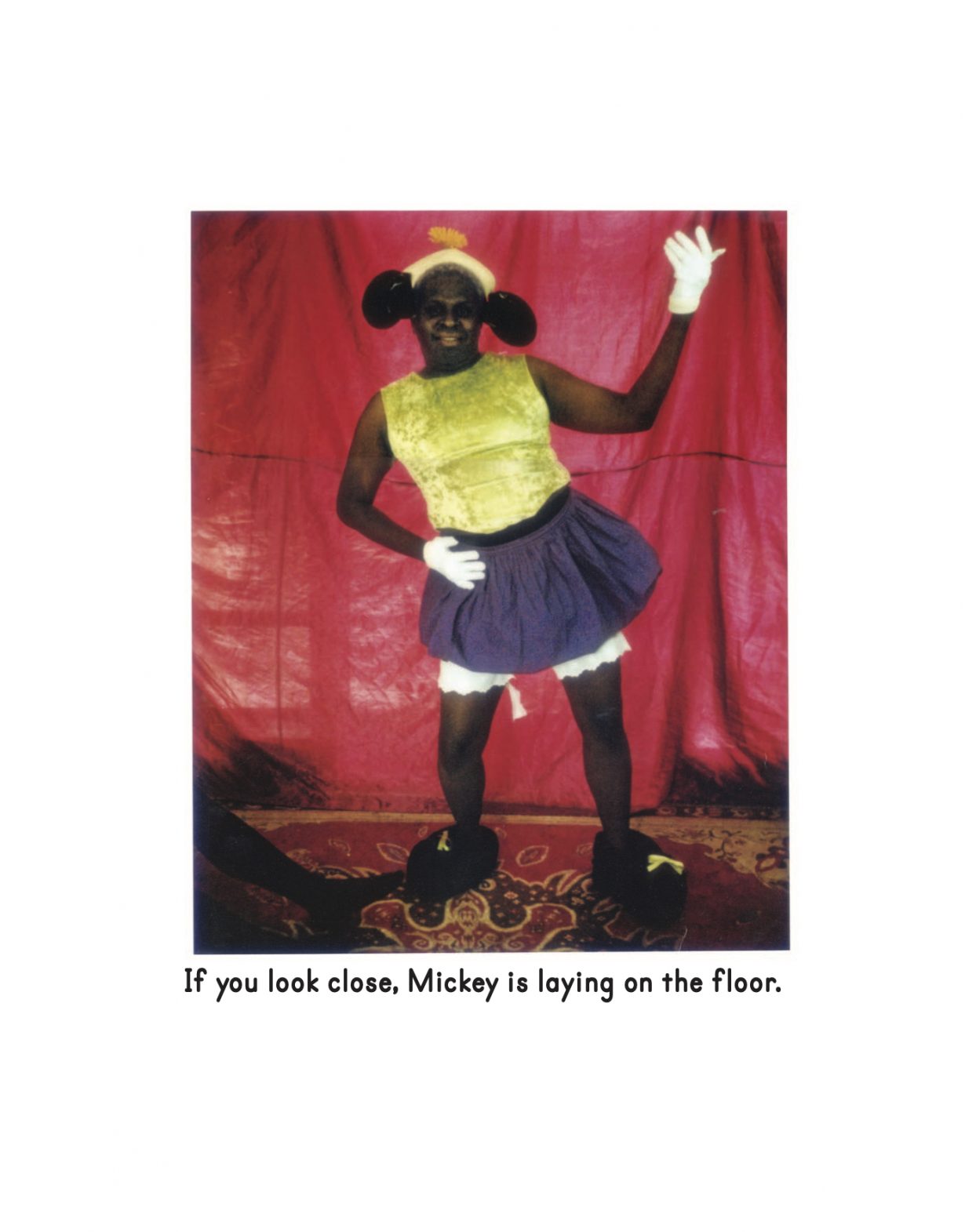

But the toys often appear in her photographs (as well as installations and videos) in mutilated, incarcerated or trapped, manipulated and neglected forms. For example, in Axed (1994), Melancholy (2005) and Smile (2017), the dolls have been decapitated, the torso and head of one stuffed into separate halves of a watermelon, another a victim in a crime scene found alongside the murder weapon, and two heads placed side by side like eyes above a boomerang gazing out over the tool’s curve to set off a bland smile. The dolls in Arrears Windows (from the 2009 series It’s playblak time: A neighbourhood watch in 15 acts) hang out of stacked milkcrates that represent poor public housing projects: ‘We all know somebody who enjoys watching or spying on their neighbours,’ Deacon wrote in Artlink. ‘Peeping has perv connotations – someone with a kink in their head – but neighbourhood watching has more to do with sticky-beaking in a seemingly sociable way. Most of us Indigenous people are used to getting stared at and being looked at with suspicion and/or contempt and in my pictures I like to allude to the darker side of life.’ Deacon’s tone is as arch as it is acerbic. Escape (2017) speaks directly to the disproportionate incarceration rate of people born into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island communities via the image of two dolls trapped behind and tangled in a wire frame. White dolls make an occasional appearance: in Daisy and Heather discuss race (2016) a black doll sits next to a white doll. It’s fun to imagine that their conversation has made Heather’s head explode in a moment of hand-wringing self-reflection – while Daisy chuckles alongside.

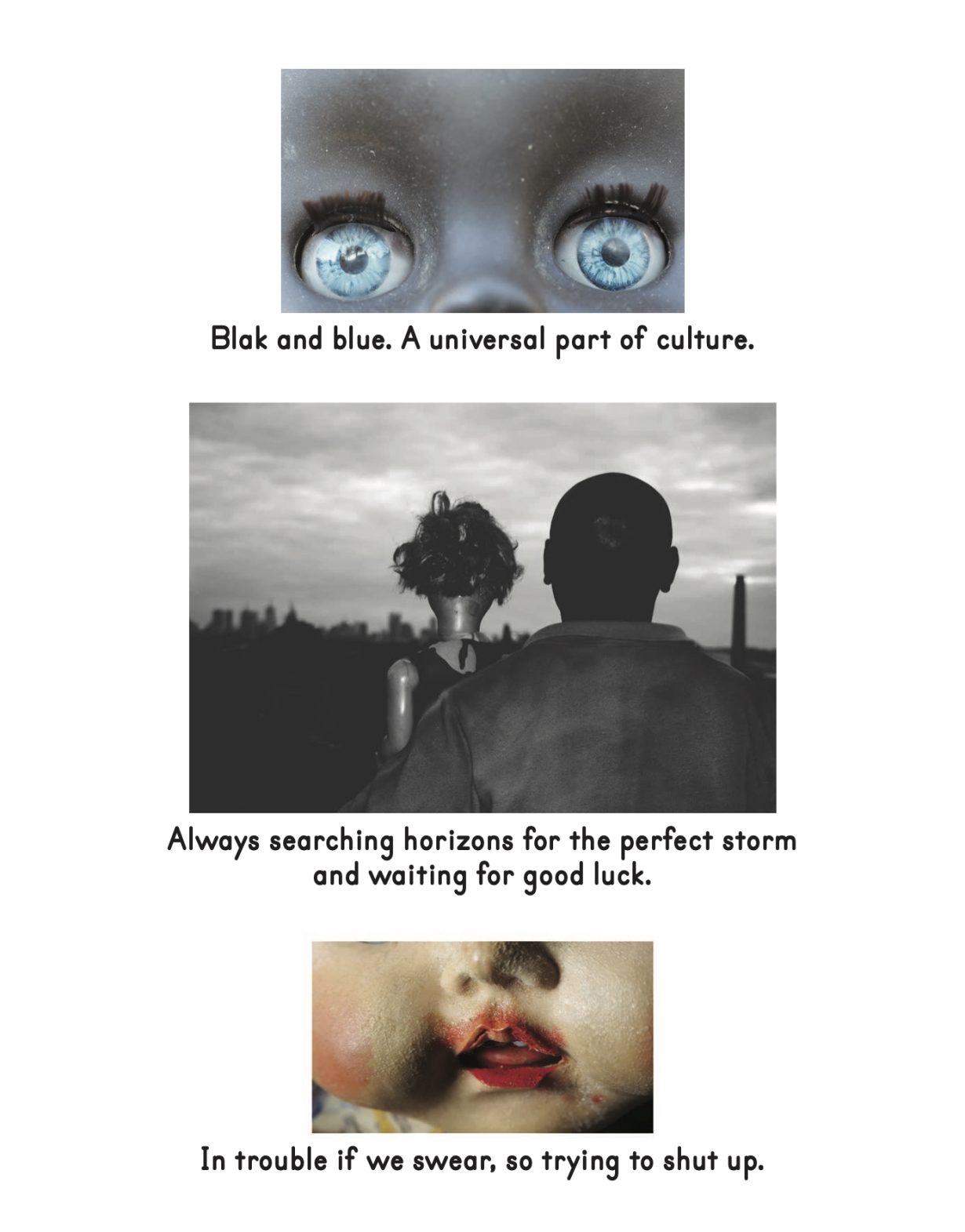

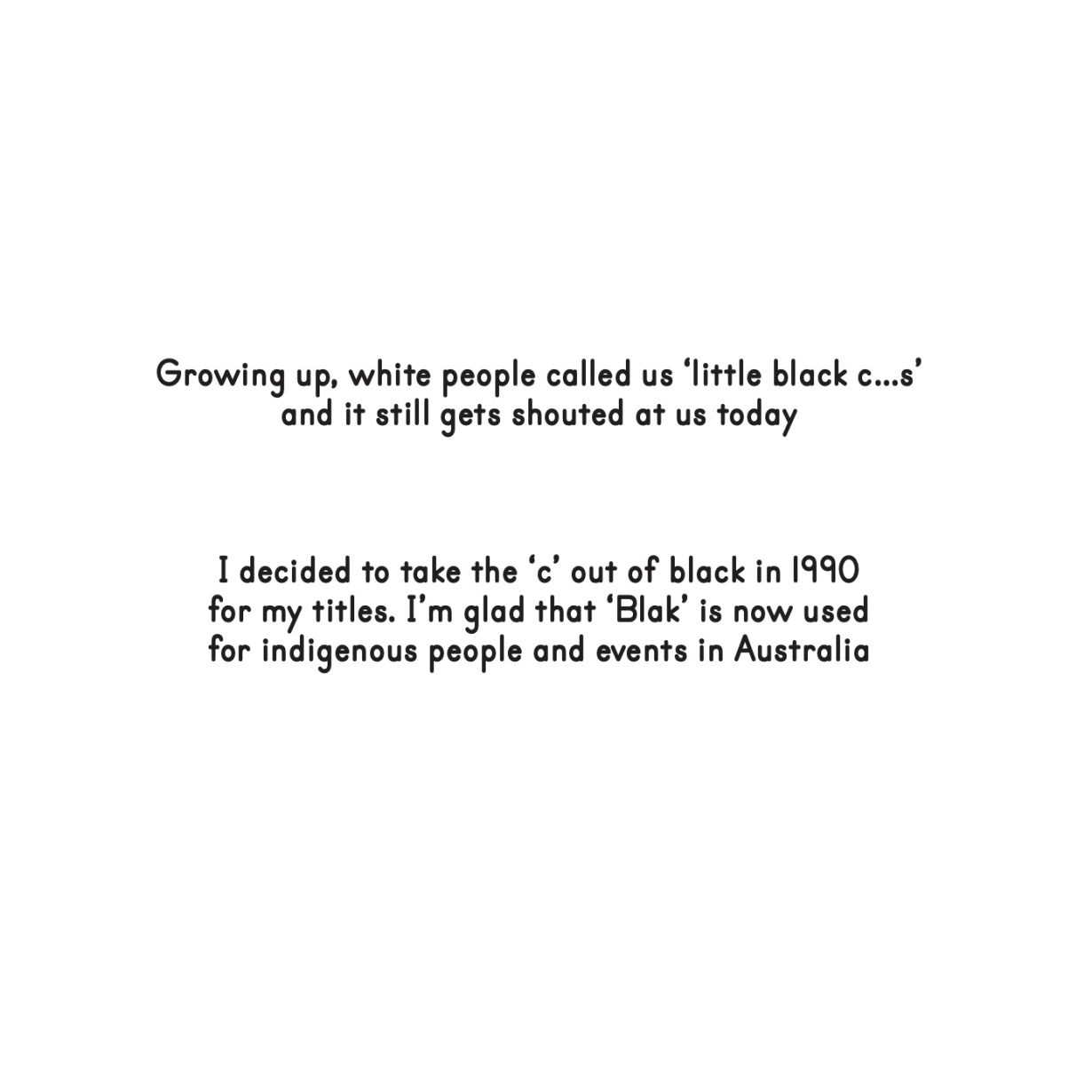

Deacon opens this visual project in ArtReview with one of her most recent photographs: Blak (2020). The term was coined by Deacon (and is also often traced to her photographic triptych Blak lik me, 1991) and continues to be used by Indigenous communities in Australia as a means of self-determination. Its specificity lies in the reclamation of the word ‘Black’, understood by Deacon to be a concept imposed on Indigenous people by the continent’s colonisers, where the omission of the letter ‘c’ transforms it into a term that is now used to describe contemporary Aboriginal culture, history, art and shared social experiences, rather than racial categorisation. Produced during Melbourne’s strict and now-more-than-five-month-long lockdown, this project pairs a selection of images and words chosen by Deacon to describe the continued racial violence towards and injustices faced by Indigenous people while also dealing with a pandemic lockdown that calls to mind a history of being locked up.

DESTINY, Deacon’s first major institutional show in over 15 years, at National Gallery Victoria, first opened in March and features specially commissioned work alongside works made throughout her 30-year career with artist and longtime collaborator Virginia Fraser, and early videoworks created with the late Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi photographer Michael Riley and West Australian performance artist Erin Hefferon. Among the photography, video, sculpture and installation on show, the exhibition also includes a living room-like installation in which visitors can discover Deacon’s ‘Koori Kitsch’ collection.

DESTINY is on view at National Gallery Victoria, Melbourne, 23 November 2020 – 14 February 2021

Featured:

Blak, 2020, lightjet print, 100×215cm

Dolly eyes (h), 2020, lightjet print, 24×39cm

Man and doll (c), 2005, lightjet print from orthochromatic film negative, 81×111cm

Dolly lips, 2017, lightjet print, 24×39cm

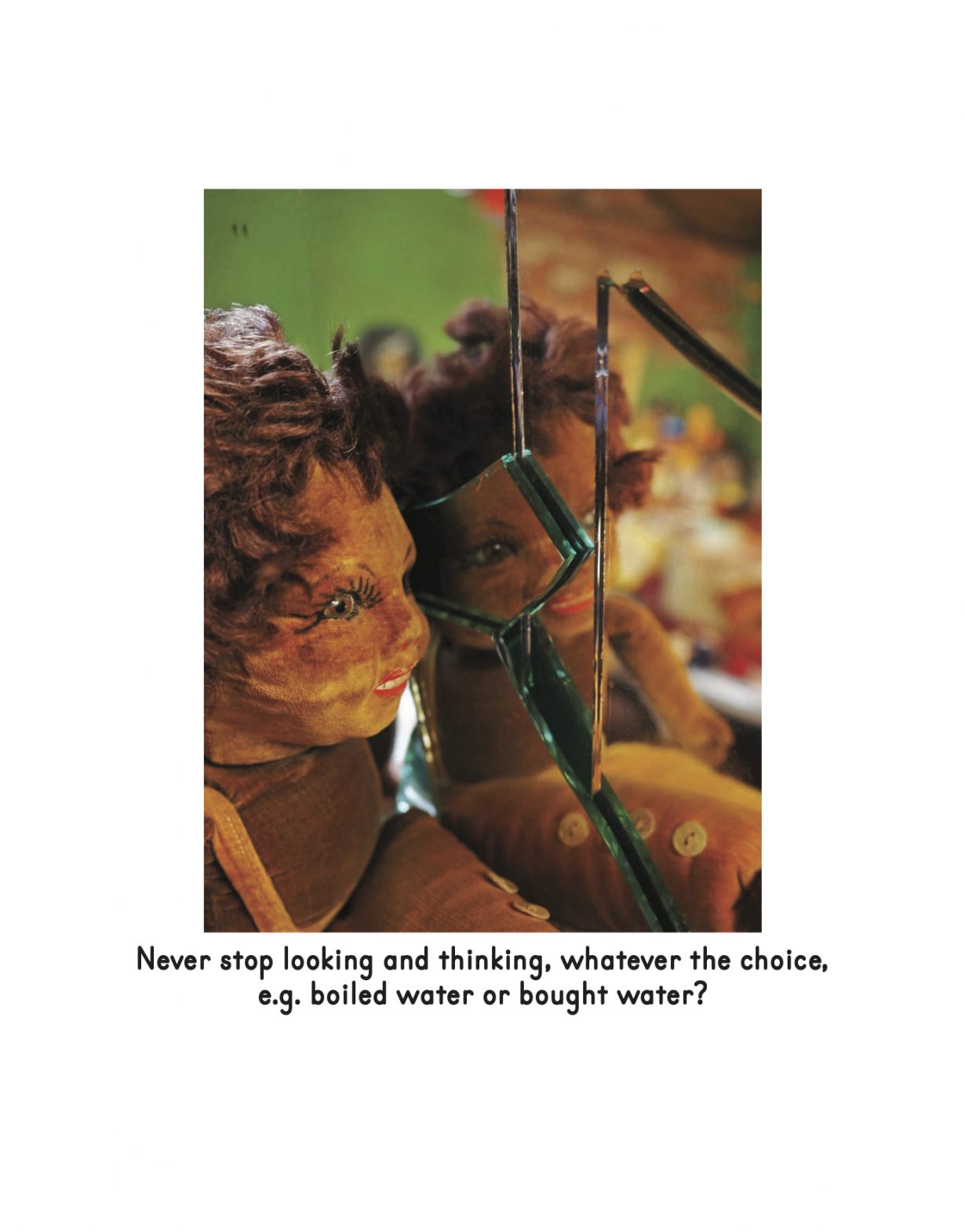

On reflection, 2019, 100×80cm

Ebony and Ivy face race, 2016, lightjet print mounted to Dibond, 58×46cm

Daisy and Heather discuss race, 2016, lightjet print mounted to Dibond, 124×99cm

Me and Virginia’s doll (Me and Carol), 1997, lightjet print from Polaroid, 100×80cm

Come on in my kitchen, 2009, inkjet print from digital image on archival paper, 80×60cm

Over the fence, 2000, Lambda print from Polaroid original, 80×100cm

Whitey’s watching, 1994, Lambda print from Polaroid original, 80×100cm

Arrears windows, 2009, inkjet print from digital image on archival paper, 60 × 80 cm

Smile, 2017, lightjet print, 102×127cm (framed)

Where’s Mickey?, 2002, Lambda print from Polaroid original, 109×91cm

all images Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney