Such is the influence of Veronika Radulovic, a German artist who lived in Vietnam during the 1990s and early 00s, that most anyone familiar with contemporary Vietnamese art will have heard of or been to visit the trove of archives under her care in Berlin. Now Radulovic, together with veteran curator Annette Bhagwati, has published an important work of Vietnamese art history focused on the four artists she considers representative of the 1990s: Truong Tân, Nguyen Minh Thành, Nguyen Quang Huy and Nguyen Van Cuong.

Four contextual essays by Radulovic and other contributors are followed by individual sections on each artist, and some 1,387 documents: photographs of artworks, images of exhibitions and performances, vernissage invitations, installation sketches, art criticism from home and abroad, excerpts from exhibition essays, as well as candid pictures taken in a tiny Hanoi apartment at 54A Hàng Chuoi, where Radulovic used to hang out with this quartet. The pictures hint at the private life and intimate creative atmosphere between Radulovic, a foreign white woman, and the artists, Vietnamese and male, that at times suggests an air of overfamiliarity. The works from the seven-year period indicated in the book’s subtitle were created as if in the blink of an eye, predominantly as ink and watercolour drawings or paintings on dó paper, or as performances in the artists’ homes and outdoor spaces. They painted shapes and words everywhere, spilling out of canvases, scattered on walls and fridges, as though expressing their frustrations in any way they knew how. Nguyen Van Cuong’s paperworks highlighted the objectification of women in a newly consumerist economy. The large watercolour paintings on paper by Nguyen Quang Huy create characters that are both human and Buddha, lost in a spiral, like a life undergoing rapid transformation.

In 1993, as part of an exchange programme between Vietnam and Germany, Radulovic took an intensive course on lacquer at the Hanoi University of Fine Art; she soon received contracts to lecture in art history at the university, which extended her stay, as well as her involvement in the local art community, until 2005. The book’s publication coincides with the 35th anniversary of the Đoi Moi reforms, introduced in 1986 during the 6th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam. These reforms marked the beginning of Vietnam’s transition to a market economy; the influx of foreign information and visitors, alongside an increased number of underground spaces, created a wave of alternative – both in subject and style – artistic and cultural production. But to frame it like this would seem to go against art-historian Pamela Corey’s argument (in an essay collected here) that Vietnamese artists are viewed through the lens of Vietnamese politics before anything else.

What’s clear is that artists of this era wanted to break free from the essentialism and representation of grand narratives that arose from either collectivism or the expectations of Western discourse, even if those grand narratives play a part in the artists’ journey to discover their sense of ‘self ’. The self as pioneer, who longs to manifest an uninhibited subject that bounces, teases, jokes and bares its arse at life and society. The self that wants to paint humans as long as they bear the artist’s own face, as in the paintings of Nguyen Minh Thành. Or in the video Diplomat-Group in Berlin (1999), in which Huy, Thành and Tân are shown conversing in a living room. As the title suggests, the trio behave excessively properly, like naive young governmental officers adjusting their mannerisms to suit a Western space or adhering to an idea of Vietnam cooked up by the West. All this for a work created as a replacement for another Truong Tân video, which had been pulled from the Gap Viet Nam exhibition at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin for its explicit gay sex.

Translated from the Vietnamese by Thái Hà

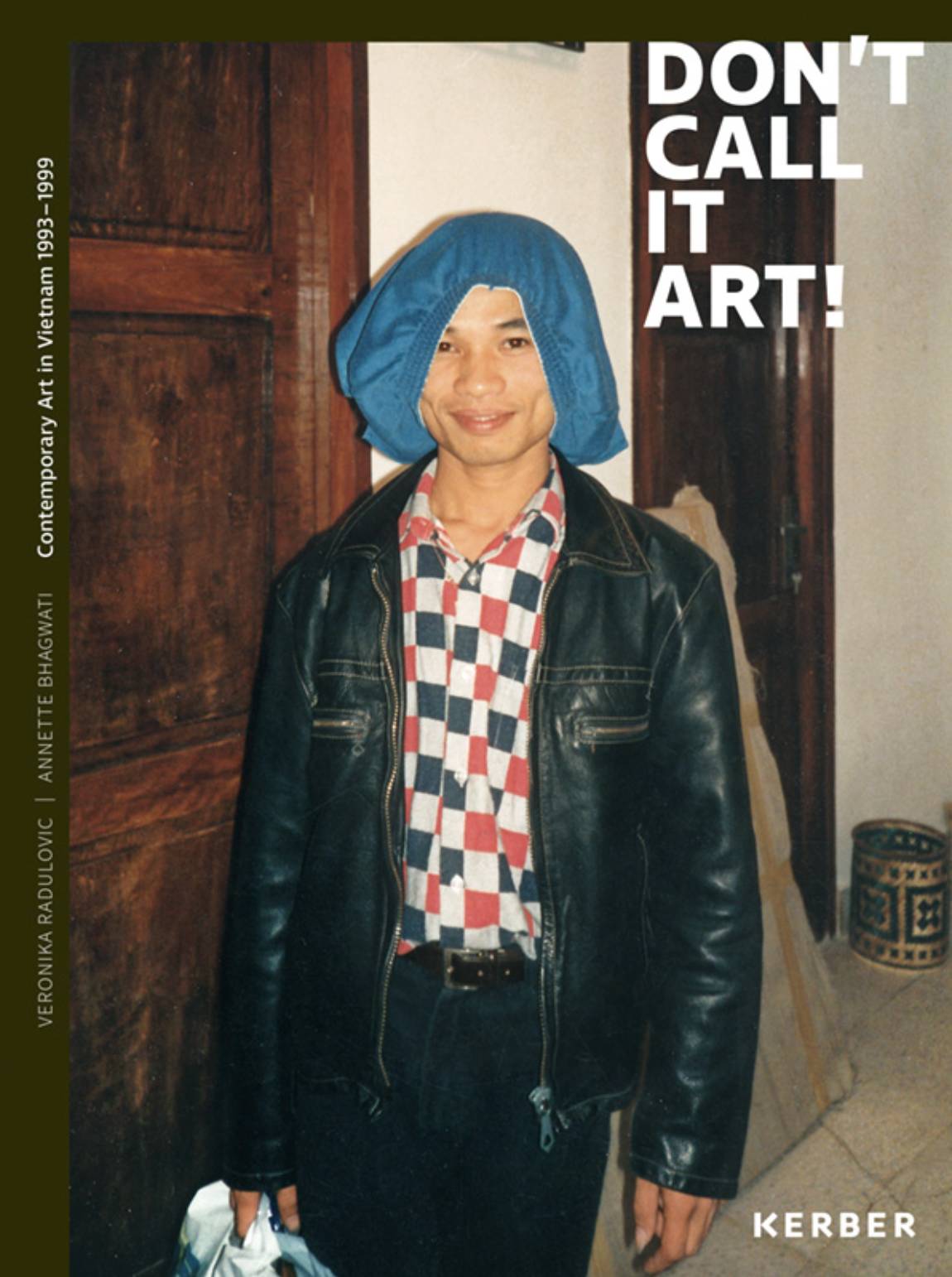

Don’t Call It Art! Contemporary Art in Vietnam 1993–1999, edited by Annette Bhagwati and Veronika Radulovic, is published by Kerber Verlag, €50 (hardcover)

From the Autumn 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia